Introduction: Political Communication in Times of Crisis

The COVID-19 virus was first identified in December 2019 in Wuhan, China. In the beginning of 2020, this obscure virus reached Europe and other parts of the world. In the beginning of March, the Italian government ordered a lockdown of parts of the country, and many other countries would follow, as it became clear that nations were experiencing a worldwide pandemic. The amount of virus-related coverage of news media across the globe increased exponentially as concerned publics seemed eager to know more about this imminent threat. The health crisis profoundly affected almost all aspects of social, economic and political life for people across the globe. This book deals with the meaning of this unseen crisis for the interactions between politicians, journalists and citizens. Did the crisis suddenly change how political leaders communicate with the public? Did journalists report more or less critically about government policy? What was the balance between traditional media and social media in these insecure times for becoming informed about the virus? These and other questions ask for a deeper investigation in how the COVID-19 pandemic has changed, challenged or confirmed the traditional rules of the political communication game.

The increasing importance of communication processes in the world of politics has contributed to the growing importance of the study of political communication, which has become an established subfield in both communication science and political science in countries across the globe. The theoretical origins of political communication not only come from these two disciplines, but also insights from sociology, psychology and economics “have helped illuminate the role of communication in shaping the conduct of politics” (Bennett & Iyengar, 2008: 712). The interdisciplinary nature of the field makes it not easy to clearly define what it is, and what its main object of study is. Although the field of political communication is wide and fluid, there is fairly broad consensus that it deals with the interactions between three central players: political actors, citizens and journalists (e.g. McNair, 2003). Often depicted as a triangle between media, public and politics, with arrows of influence going in all directions. However, the exact composition and role of these three actors are not a given. In particular as the field seems to study an object that continually evolves—including the growing disconnection between citizens and political institutions, major developments in communication technologies, structural changes in media environments and the rise of online disinformation (Bennett & Pfetsch, 2018; Blumler, 2015; Van Aelst et al., 2017). For instance, social media platforms are difficult to conceptualize in the politics-media-public triangle as they are a tool and a platform that are used by all three actors, but also operate as an actor on their own (Klinger & Svensson, 2015). Therefore, we define ‘media’ not narrowly as traditional journalism, but broadly including alternative digital outlets and platforms that often take a much more activist role in (mis)informing the public.

This book seeks to explore how a crisis like the COVID-19 pandemic confirms or rather questions some of the classical ways policymakers, citizens and different types of media practitioners interact. Several scholars have shown that in times of crisis the rules of the game can change. For instance, in the case of an unexpected event such as a terrorist attack or an environmental disaster, journalists and politicians alike are less prepared. This means that media coverage is less driven by traditional news routines, and politicians need to think out of their ‘strategic communication box’. Based on the work of Lawrence (2000) on police violence, we know that dramatic events have the ability to change how an issue is discussed and defined in the press, and offer the possibility for outsiders to challenge the traditional dominance of elite actors in the news. We also know that in times of crisis the public might feel a higher need for information and orientation. Althaus (2002) showed, for example, that in the week after the 9/11 terrorist attacks the television network audience doubled. Multiple other studies, on a range of dramatic events, confirm that people turn to the news in times of fear and uncertainty (e.g. Boomgaarden & de Vreese, 2007; Casero-Ripollés, 2020; Westlund & Ghersetti, 2015). Previous studies have suggested that during a crisis uncertainty can trigger anxiety which people try to reduce by seeking more information (e.g. Lachlan et al., 2016). Finally, we also expect politicians to change their policy and communication strategy in reaction to an exogenous shock. Scholars in political science and public administration have, for instance, documented how leaders addressed and communicated differently about the economic crisis of 2008 (e.g. König, 2016; t Hart & Tindall, 2009). However, a major health crisis might be an even bigger challenge. “Nothing tests a government leader like a deadly pandemic” (Kahn, 2020: ix). Kahn, an expert on leadership in times of health crisis, argues that a pandemic is a multidimensional crisis and that a leaders’ response impacts all aspects of social and political life.

So there is little doubt that a pandemic is not simply a dramatic event, but perhaps more comparable with war time, when people are dying, fear for their lives or cannot perform their job anymore. In this context of military conflict and anxiety, the support for leaders is often stronger than ever. Political scientists have documented this positive side effect that became known as the ‘rally-around-the-flag’ theory. This concept of a rally-around-the-flag will be used as a way to organize the different contributions to this book. We do so for mainly two reasons. First, while a rally effect might be expected during such a profound crisis (see further), it is really more complicated than that. Because of national differences in leadership and communication, fragmentation in media ecologies, and growing polarization of electorates and media landscapes, there can be a huge variation in the presence and duration of a rally effect. The different chapters in this book provide the necessary national context or comparative insights to understand this variation in leadership approval. Second, the rally-around-the-flag effect basically involves the three central players in political communication. Although most scholars have focused on the reaction of the national leader, the interaction with and between media actors and ordinary citizens plays a crucial role. Therefore, we will first discuss the rally-around-the-flag from this broader political communication perspective.

Rally-around-the-Flag from a Political Communication Perspective

The rally-around-the-flag theory basically claims that in times of crisis the popularity of and trust in the political leader of the country increases. Confronted with a sudden attack or threat to a country, the public is expected to form ranks behind its leader and the flag (Brody & Shapiro, 1991). Research shows that an important pre-condition for a rally effect is that the opposition (temporarily) refrains from critiquing the government (Hetherington & Nelson, 2003). Mueller was the first to systematically study this effect in the context of US foreign policy. He argued that rally effects occurred when the president of the USA was involved in international events with a specific and dramatic focus. Mueller mainly referred to military interventions and ongoing wars, but also included important diplomatic events and major summits (Baker & Oneal, 2001; Mueller, 1973). Later on the theory was mainly applied in the context of violent conflicts, and on terrorist attacks in particular (Chowanietz, 2011). In the aftermath of the terrorist attacks of 9/11, President Bush enjoyed a boost in his popularity that was stronger (+35 percent points) and lasted longer (more than a year) than in any other case in history (Hetherington & Nelson, 2003).

During the last two decennia, the theory has been applied also in a broader range of contexts and types of crises. Most recently, scholars are using the theory to study the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on the popularity and trust in governments (e.g. Bol, Giani, Blais, & Loewen, 2020; Shino & Binder, 2020), thereby extending the focus on mainly military events to an unprecedented international health crisis. In line with these studies, the pandemic in many ways is an ideal case to test a rally effect. In addition, we argue that the rally-around-the-flag effect basically involves the three central players of political communication. Since the theory has been mainly used by scholars in international politics and public opinion, the focus has been on government leaders and the public, leaving the role of the media largely out of sight. Only a few studies have explicitly included the important intermediary role of media coverage into their design. In their study of military interstate conflict, Baker and Oneal (2001) found that the amount of coverage by the New York Times played a significant role in the presence or absence of a rally effect. The work of Baum and colleagues has elaborated more on the specific role of the media in connecting political leaders and the public in times of crisis (Baum & Potter, 2008; Groeling & Baum, 2008). They argue that an increase in popularity of the government and its leader is less determined by the objective characteristics of the crisis, but more by how governments communicate about it, to what extend the government’s handling of the crisis is criticized by the opposition and how this political debate is reported in the news. Groeling and Baum (2008) state that journalists seldom simply parrot statements of the political elites, but play an active role by selecting and ignoring certain actors and messages. Only in very unique dramatic incidents (like the 9/11 attacks), both the opposition and the media lower their normal critical voices, and a positive rally effect around the flag and the leader becomes possible.

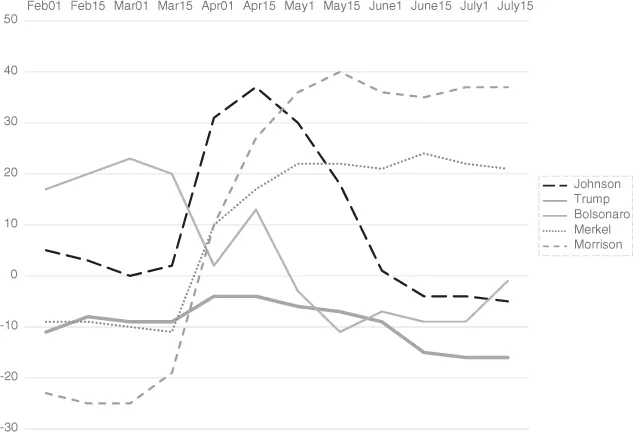

This raises the question whether the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic is a similar ‘exceptional’ event that could have a similar effect on the public’s perception of its leader(s). Recent studies show that as a consequence of the coronavirus a clear rally effect happened in many countries across the globe, but not in all and in many cases the effect was short-lived (e.g. Bol et al., 2020; Herrera, Ordoñez, Konradt, & Trebesch, 2020). This suggests that the rally-around-the-flag effect is contingent on different factors related to the interactions between political actors, media players and citizens. Before elaborating on these conditions, we focus on some concrete cases that clearly show the variation in rally effects across countries.