![]()

Chapter 1

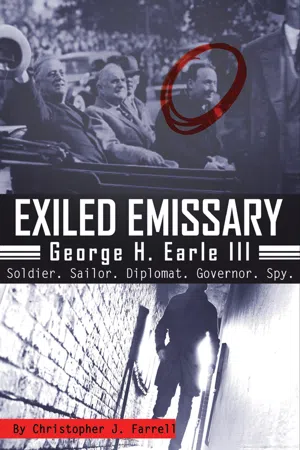

Earle and FDR

Millions of American men and women would gladly have given their lives if it meant ending World War II a day sooner than it did. I believe one man had a chance to shorten the conflict by more than 18 months – and brushed it off. His name? President Franklin D. Roosevelt.1

George H. Earle III

Former Governor of Pennsylvania,

U.S. Minister to Austria and Bulgaria

Assistant U.S. Naval Attaché, Istanbul

Philadelphia, PA

July 1958

♦

… I specifically forbid you to publish any information or opinion about an ally that you have acquired while in office or in the service of the United States Navy. In view of your wish for continued active service, I shall withdraw any previous understanding that you are serving as an emissary of mine and I shall direct the Navy Department to continue your employment wherever they can make use of your services.2

Letter from President Franklin D. Roosevelt to

Commander George H. Earle III, U.S.N.R.

March 24, 1945

♦

George H. Earle III told President Franklin D. Roosevelt two things FDR simply did not wish to hear:

1. In January 1943, German intelligence, diplomatic and military leaders offered to turn over Adolf Hitler and his inner circle, dead or alive, to the Allies under terms of an Armistice, and an agreement for a subsequent attack on the Soviet forces moving west through Central Europe; and

2. The Katyn Forest Massacres in April and May 1940 – wherein more than 22,000 Polish military officers, government officials, academics, business owners, lawyers, priests, and others (“decapitating” Polish society) – was carried out by the Soviet NKVD (“People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs,” the Soviet secret police) over claims the Nazis had murdered the victims in 1941.

As to the first point, FDR’s response to Earle was silence. Since January 1943, Earle served as the “Assistant U.S. Naval Attaché” in Istanbul, Turkey as FDR’s personal emissary to the Balkans – thin diplomatic cover for Earle’s activities in a wartime neutral city renown for intrigue, espionage, and the occasional body found floating in the Bosporus. Months passed following Earle’s stunning message conveying the proposal from the German resistance (“Widerstand” in German). Earle sent follow up dispatches via diplomatic pouch to FDR, and had clandestine meetings with German resistance leaders who articulated detailed plans for the neutralization of Hitler, installation of an interim German government, and the means of establishing contact with Allied armies for an immediate armistice on the Western Front. Eventually, Earle got his answer from FDR: “All such applications for a negotiated peace should be referred to the Supreme Allied Commander, General Eisenhower.”

Earle memorialized his reaction to FDR’s reply: “In diplomatic language, this was the final runaround. Even if we did get to Eisenhower, the matter would be referred back to Roosevelt for a final decision. The President’s answer was therefore a clear indication of his complete disinterest in this plan to end the war.”3

The German resistance, stunned by Roosevelt’s rejection and demand for “unconditional surrender,” took the decision to move on to the last-ditch July 1944 bomb plot, known as Operation Valkyrie, executed by Colonel Claus Graf von Stauffenberg at Hitler’s Wolfsschanze (Wolf’s Lair) headquarters in East Prussia. The assassination attempt failed and much of the German resistance leadership was arrested and executed.

Concerning Earle’s Katyn Forest Massacre investigation and findings – that the Soviet NKVD had brutally slaughtered the cream of Polish society – FDR rejected the autopsy reports, interviews, sworn affidavits and other evidence Earle compiled from the International Committee of the Red Cross, neutral observers, and Earle’s own network of Central European agents. FDR insisted that Earle’s evidence was merely German propaganda. “George,” said Roosevelt, “the Germans could have rigged things up.” FDR ordered Earle’s report suppressed.4

Earle was vindicated in 1989, fifteen years after his death, when the Russian government officially acknowledged and condemned the perpetration of the Katyn Forest Massacres by the NKVD, as well as the subsequent cover-up by the Soviet government.5

Earle defined his understanding of the real threat to Western Civilization posed by Soviet Communism in classified “Eyes Only” cables to the President since April 1944. As presidential emissary to the Balkans, Earle had interviewed hundreds of Soviet refugees and developed his own source network that reported on the depravity of the Red Army as it rolled west.

In May 1944 and March 1945, Earle and FDR had heated exchanges in the White House over the threats posed by the Soviet Union in post-war Europe. After the March 1945 White House meeting, Earle notified FDR of his intention to publish his findings concerning the Katyn Forest Massacre and the looming Soviet threat to western democracy. FDR forbade Earle to publish any such information or opinion, withdrew Earle’s status as presidential emissary and exiled the former Pennsylvania governor, ambassador, and attaché to be deputy military governor of Samoa.

The exile of a presidential emissary, more than 7,000 miles from Washington, DC, illuminates the character of both FDR and Earle. It is the difference between a political ideologue, blinded to one course of action at any and all costs, and a man of conviction sounding the clarion call with a clear vision of the impending Soviet threat that would freeze the world into a half-century long Cold War that cost the world thousands of lives and millions of persons’ political imprisonment. Within four months of the shameful banishment to Samoa, FDR was dead, and President Truman would recall Earle home to the United States.

As we shall see, newly declassified “Top Secret” records unearthed from government archives will provide new context for evaluating the amazing career and predictive analysis of George H. Earle III, and raise compelling questions and fresh answers concerning:

• How World War II might have ended 18-months earlier;

• The Soviet intelligence penetration of the FDR White House and the Soviet influence campaign for post-war Europe;

• What happens when the full weight of the government is turned against a man of integrity who is “guilty” of telling the truth.

♦

![]()

Chapter 2

February 10, 1918 USS Victor

On patrol off Cape May, New Jersey

Under a steel-gray sky, the crew of the USS Victor, a 72-foot, 50-ton, wooden-hulled, motor patrol boat was on watch for German submarines at the entrance to Delaware Bay.

The Victor patrolled between Cape May, New Jersey and Lewes, Delaware, occasionally venturing upriver as far as Reedy Island. The winter of 1917-18 was the most severe in more than a decade, and Delaware River icepacks were at unprecedented levels, extended for miles seaward.6

The deck log for the Victor records that at 13:00 hours that Sunday afternoon, the patrol boat stopped and inspected a three-masted schooner sailing out from Puerto Rico and bound for New York City with a cargo of sugar.7

At 15:30, without warning, the Victor’s motor crank case exploded in the engine room, igniting a raging fire. The fire spread quickly, threatening the boat and crew, as the flames extended their reach towards the Victor’s 1100 gallons of gasoline in its main and reserve tanks. Smoke plumed from the engine room.

The Victor’s commanding officer, Ensign George H. Earle III and Machinist Mate First Class James J. Logan rushed to the engine room to fight the flames with fire extinguishers. Ensign Earle’s fast, clear commands to the Victor’s complement of ten crew members resulted in the formation of a bucket line from the stern to the engine room. Meanwhile, the remaining hands on deck hoisted an upside-down national ensign and distress signal flags, fired the boat’s one 3-inch gun, and sounded the Victor’s klaxon horn.8

Suffering burns, yet still returning to the engine room fire, Earle had ordered the Victor’s small boat manned, lowered, and sent out for assistance at 15:40. Other crew began to construct a makeshift raft out of doors, tops of berths, hatchways, and tables. Life preservers were on deck. Perhaps more importantly, the crew moved all ammunition (600 rounds for the heavy gun and 6000 rounds for the machine guns)9 astern to prevent its catching fire and exploding.

Battling a raging fire and overwhelming smoke, Ensign Earle and Machinist Mate Logan returned again and again to the engine compartment in an effort to quench the flames. With the engine inoperable and steerage way lost, the Victor’s helm did not answer. She was dead in the water and adrift in the currents at the mouth of the bay. At 15:50, “…the fire gained headway, and chances for putting it out looked bad.”10

Without a wireless radio set, the crew of the Victor was at the mercy of the engine room fire, and the near-freezing waters at the mouth of the Delaware River. The air temperature hovered at 34 degrees with moderate southwest winds that February afternoon.

Finally, Earle, Logan and the firefighting crew brought the engine room fire under control by 16:00. The Victor’s deck log reflects that the fire was completely extinguished by 16:10.11 Men were posted at stations to watch in case a fresh fire started. The Victor’s anchor was lowered in order avoid drifting into shallow waters.

Shortly after 17:00, Ensign Earle ordered the “SOS” signal transmitted by “blinker” — a signal lamp producing a pulse of light for Morse Code communications. He also ordered red signal rockets fired over the Victor.

At 18:00, the searchlight of the USS Emerald (S. P. 177) swept across the Victor. By 18:35, the Emerald arrived on the scene and began towing the Victor. Due to heavy swells running and navigation challenges, the Emerald and Victor arrived at Cape May at 00:45, November 11. 1918.12

For their extraord...