![]()

Introduction to Volume 1

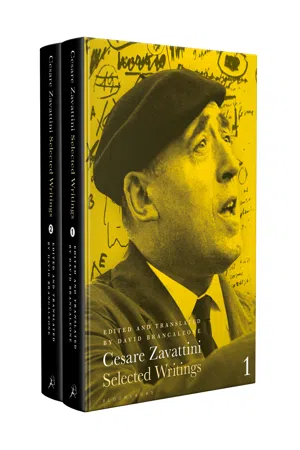

The purpose of this anthology is to fill a gap in film history, by making available in English a representative selection of Zavattini’s scenarios in Volume 1, and film writings, interviews, diary entries and other texts, in Volume 2. This arrangement will offer the reader a head start into Zavattini’s cinema as a whole.

Zavattini’s international reputation is based on his scenarios and screenplays, particularly for major post-war European classics, key Neo-realist films: Sciascià, Bicycle Thieves, Miracle in Milan and Umberto D. But his earlier film writing is little known. The same is true as regards the subsequent direction of Zavattini’s film writing and activity in general. For equally shrouded in the mists of time are the years that followed historic Italian Neo-realism. Humour informs his 1930s and early 1940s film writing. The war marked a clean cut and new directions, and yet ties with the 1930s also exist. A paradox which has not been addressed to date.

There are as many facets to Zavattini as there are areas of his interests which materialize as areas of direct involvement and tangible contributions to a range of fields. For as well as a screenwriter, he was also a film theorist, a publisher, a pioneer of visual culture in Italy, a Modernist author of literary texts, a visual artist, a campaigner for socially engaged cinema, a campaigner for human rights and a campaigner against atomic war, in the years between 1948 and throughout the years of the Cold War. This explains why he was awarded the Lenin Peace Prize by Moscow in 1955, alongside the documentary filmmaker Joris Ivens. His was an expanded film practice, consisting in what he did on paper and what he did in the cutting room, his field research, but also all his efforts towards a New Italian Cinema. As he said in an interview:

I spent at least fifty percent of my time fighting for Italian cinema. I don’t think anyone devoted as much time as I did towards socially engaged cinema. Years and years given, with all the consequences. I was made to pay for all this, and there is also the fact that they were simply unable to do it, even if they had wanted to. An enormous amount of activity and of all kinds: hundreds and hundreds of meetings, public interventions, conferences, debates, serving to organize Italian cinema. At what risk? The risk you run when you say what you think.1

All these areas of engagement could not fail to inform his film practice. They have been explored, to some extent, to date, but always in isolation. Until now, the Aladdin’s Cave of archival material stored in the Zavattini Archive of Reggio in Emilia at the Panizzi library has been little researched, though this is where to find not only interviews and conference papers, but his entire, gargantuan, correspondence (numbering over one hundred thousand documents), all neatly filed away at the time, in duplicate, in his own research.

From the days of his earliest involvement in screenwriting, Zavattini published his scenarios, even before the release of the films. In 1979, he collected a selection of his film scripts in two anthologies. Basta con i soggetti! (1979), published in the latter years of Zavattini’s life, comprises twenty-five scenarios. What is remarkable is that this selection included none of the canonical scenarios or stories. One can only surmise that the reason for these glaring omissions was a choice not to memorialize his whole life’s work, but, instead, to provide a background for those projects he was still keen to get into production. A glaring example is Tu Maggiorani (You Maggiorani). Zavattini chose to include a story, based on real events, about Lamberto Maggiorani, the protagonist of Bicycle Thieves, while he omitted world-famous Bicycle Thieves. The second anthology was edited twenty years after his death. Uomo vieni fuori! (2006) filled those otherwise inexplicable gaps, providing an essential and generous selection, including six major pre-war film scripts.

This English anthology offers an equally substantive selection, comprising thirty-nine scenarios, two treatments and a selection of other writings to supplement it. This edition takes into consideration the important fact that Zavattini was also the author of a bestselling pre-war trilogy of short stories, or raccontini and longer stories, fictional accounts from Your Own Correspondent, written in the late 1920s and early 1930s, about Hollywood. It therefore includes, on Arturo Zavattini’s suggestion, a representative selection of his father’s pre-war literary writings, including a selection of seven of his raccontini, those short, aphoristic stories, sometimes consisting in no more than a few lines. Also included is a selection of his fictional interviews and stories about Hollywood, published in Italian film magazines of the era. This anthology also contains correspondence relating to key projects, documents that shed light on the creative process, for example, to contextualize a major project, such as Italia mia and the related film book Un paese.

This interdisciplinary approach enables the reader to see how certain ideas, which have always been perceived as belonging entirely to the post-war period, not only originated much earlier but also demonstrate how a similar thread of ideas can resurface in a very different context or a different medium. In the best example, one discovers that the whimsicality of Miracle in Milan, and what seems to be a surreal vein, is a major characteristic of his early literary work and the nucleus of ironic, nonsense-based raccontini. Take a famous scene, featuring a mathematics contest. Originally, it appeared as a few lines, a sketch, in the tradition of Italian popular comic nonsense writing, or scemenze (literally ‘stupidities’), but later became a scene in the film, as did others, from the same source.

Indeed, Zavattini’s writing career, from its inception in the 1920s, and the reputation he soon established, centred on humour, as the short stories from his trilogy demonstrate. As for the Hollywood stories, very early on, in 1927, he began to write stories about the Dream Factory, at the end of the Silent Era and on the cusp of the Sound Era. This anthology includes several stories from his Hollywood Chronicles, originally published in the 1930s and collected in 1991. In these, not only does Zavattini lampoon the Star System which was attracting in the same years Siegfried Kracauer’s attention as a social phenomenon (in the wake of Kracauer’s readings of Karl Marx and Georg Simmel). Zavattini also adopts Luigi Pirandello’s distancing techniques, to raise the kind of questions about the relation between reality and illusion and uncertainty, which he addresses after the war, most notably, in his scripts for Bellissima (1951), for The Great Deception (1952), for Colour versus Colour (1960) or The Truuuuth (1982), written, performed and directed by Zavattini himself.

As for the translation, it does its best to do justice to, if not match, Zavattini’s linguistic register, which is very often informal, colloquial even. If his writing resembles spoken Italian, it is for two reasons: first, he had a desired audience in mind, and second, because his writing practice consisted in dictating his stories, even his film diaries, and other texts, including his vast correspondence, to a typist. In some instances, for example, in the scenario for a documentary about the assassination of Aldo Moro, Aldo Moro: Before, During, and After (1978), also included in this edition, the linguistic register is far more complex, notable for the lack of short sentences that feature in many of the other stories and for the argumentative, essay-style approach the writer adopted. In translating Zavattini, it is very tempting to resolve his deliberate parataxis in the scenarios; pages of sentences coordinated by and ... and ... and ..., to replace them with apposite ‘buts’, ‘ifs’, ‘althoughs’ and so on. However, a familiarity with his style of film writing discourages that temptation, for example, in the treatment of Umberto D, a prime example of where parataxis is a means to an end and, as in another case, the treatment has also been translated.

At first glance, so many of his film scripts seem descriptive. Yet description conceals his phenomenological gaze on reality, one which allows the reader, in the first instance, and the viewer in the second instance, the freedom to interpret situations, by making sense of the ‘social facts’ independently, or, at least, apparently so. Parataxis serves to ensure the continuity of the present moment. It is a signifier pointing to the concatenation of moment-to-moment existence, in which being, or Being, is experienced directly, in the sense of the phenomenological being-in-the-world of sense phenomena, of sense perception, which involves direct experience. Bicycle Thieves, as early as its formulation as a scenario, presents us with what Maurice Merleau-Ponty called ‘the surprise of the self in the world’, in ‘describing the mingling of consciousness with the world, its involvement in a body, and its coexistence with others’.2

Looking at Zavattini’s work as a whole and across disciplines (literary writing, journalism, lobbying, film writing, radio broadcasting, editorship, publishing ventures), one finds that there are some recurring preoccupations that form a pattern of artistic, cultural and social intervention. The most conspicuous is Italia mia, always classified in the specialized secondary literature of Zavattini Studies and, in the Zavattini Archive itself, as progetto non realizzato: a project which never came to fruition, and therefore, it would follow, less significant than the ones which did. Yet, as Gian Piero Brunetta has recently noted, ideas travel in cinema, and projects we had assumed remained on paper were influential nonetheless.3

This cross-fertilization of ideas travels from person to person, in Zavattini’s case, it also informs one project, then another, and another, within the same person. Italia mia is a case in point, as a mapping of Zavattini’s film work in its width and breadth shows. He developed the Italia mia project, though in unexpected ways. While the international versions, México mío, Cuba mía or España mía, never made it into production and release, they were part of an overarching Italia mia project which was a catalyst for a great deal of Zavattini’s developing idea of non-fiction or documentary cinema, theorized as mainstream cinema to come.

This is the reason why this anthology, unlike Orio Caldiron’s 2006 Italian selection, includes Un paese, originally a film book, and intended as one of a number of film books to be published within an overarching Italia mia series. Such a framework justifies the inclusion of, for example, the proposed documentary Why? (1963), of the coeval The Mysteries of Rome (1963), which became a film, or the Free Newsreel La rivoluzione (1969), Revolution, buried in a letter to an associate in the Free Newsreels organization, but a useful addition to his corpus of scenarios, be they in translation or in Italian. The same critical path through Zavattini’s thought and work led him to write La veritàaaa (1982) The Truuuuth. There are countless versions of the scenario, so many different screenplays, totalling thousands and thousands of typed pages, and finally resulting in the film which Zavattini himself wrote, acted in, and directed, in some ways, a testament and a final statement. One version of the scenario is included and contextualized by several interviews about the ideas behind the film.

From a philological point of view, the text published in the 1979 and 2006 anthologies has been compared to earlier versions, where these exist, including parts which were edited out for these two collections, as in the case of Umberto D. Its original magazine edition includes a vital commentary from the screenwriter, deleted by the book editor whose version was later adopted. Zavattini’s commentary has been translated and published in the accompanying footnotes.

Any relevant archival, unpublished papers have also been used where useful for the contextual introductions.4 Indeed, every single text is preceded by detailed contextual notes to situate that text within its original frame of reference, thus making it easi er for any twenty-first-century reader, whether a student, a researcher or a general reader, to map for herself Zavattini’s film writing, both critically and historically and approach his writing as much as possible on its own terms.

A final word about Italian screenwriting and how Zavattini approached it. It must be remembered that he was a writer first and a screenwriter second. He called himself a film writer, scrittore di cinema, to signal how he envisaged writing for the cinema, and suggest that it spanned across various stages of engagement. In Italian, a soggettista is someone who writes the initial outline story, but often no more (though there are many cases of the writer and director being one and the same person, Elio Petri, for example), while a sceneggiatore is the author of the treatment and screenplay and shooting script. Zavattini worked in all these capacities, with a bias towards the outline, the initial script or what is referred to as a ‘scenario’ in this collection. He claimed that if you could sum up a story in a few words, you probably had a story worth telling, as Abbas Kiarostami, among others, often told his students. Kiarostami was a great admirer of Zavattini’s theories and approach to cinema. His film Ten on Ten (2004) devotes an entire ten-minute lesson sequence to Zavattini, cit...