- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The Iliad dealing with the final stages of the Trojan War and The Odyssey with return and aftermath were central to the Classical Greeks' self identity and world view. Epic poems attributed to Homer, they underpinned ideas about heroism, masculinity and identity; about glory, sacrifice and the pity of war; about what makes life worth living. From Achilles, Patroclus and Agamemnon in the Greek camp, Hektor, Paris and Helen in Troy's citadel, the drama of the battlefield and the gods looking on, to Odysseus' adventures and vengeful return - Jan Parker here offers the ideal companion to exploring key events, characters and major themes. A book-by-book synopsis and commentary discuss the heroes' relationships, values and psychology and the narratives' shimmering presentation of war, its victims and the challenges of return and reintegration. Essays set the epics in their historical context and trace the key terms; the 'Journey Home from War' continues with 'Afterstories' of both heroes and their women. Whether you've always wanted to go deeper into these extraordinary works or are coming to them for the first time, The Iliad and the Odyssey: The Trojan War, Tragedy and Aftermath will help you understand and enjoy Homer's monumentally important work.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Iliad and the Odyssey by Jan Parker in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Greek Ancient History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

The Iliad

Aristeia

Introduction: Exploring the Iliad

Layers

‘Ihave looked on the face of Agamemnon,’ said Heinrich Schliemann, lifting the fabulous gold mask off a figure excavated from the Mycenae shaft grave. When excavating Troy (modern Hissarlik in north-west Turkey), he dressed his wife in ‘Helen’s treasure’. Schliemann devoted his life to uncovering – in all senses – the heroes of the Iliad: so much so that he was incapable of discriminating between the perhaps nine phases of Troy’s citadel, digging through until he found fortifications that matched those he found described in Homer’s poem.

Potsherds

Editions of Alexander Pope’s Iliad had fold-out maps so that readers could explore the landscape and remains of the Trojan citadel and the Greek camp, literally treading in Agamemnon’s and Achilles’ footsteps. However, careful research by archaeologists, oral historians and textual scholars has peeled away earlier and later traditions within our text, distinguishing material culture and cultural practices of the Mycenaean or Bronze Age from those belonging to later Dark Age, Dorian or early pre-Classical cultures.

Chariot Fighting

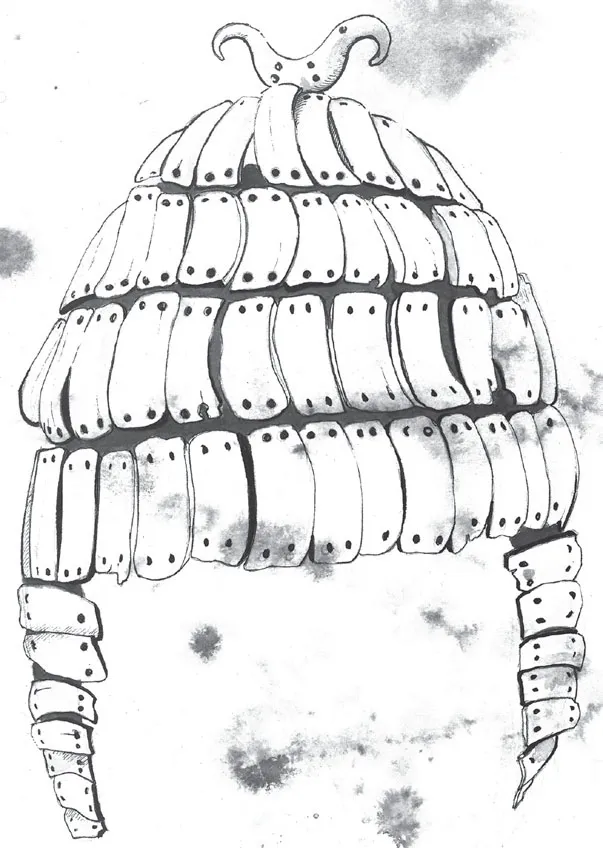

The text contains some splendid indicators, direct references for example to Bronze Age tower shields, a valuable (being exotic and precious) prize of a lump of iron, ‘Dendra’-type armour, the use of chariots from which to fight and the boar’s tooth helmet inherited by Odysseus:

Meriones gave Odysseus a bow, a quiver and a sword, and put a cleverly made leather helmet on his head. On the inside there was a strong lining on interwoven straps, onto which a felt cap had been sewn in. The outside was cleverly adorned all around with rows of white tusks from a shiny-toothed boar, the tusks running in alternate directions in each row. Odysseus’ grandfather Autolycus stole it when he robbed the Thessalian chief Amyntor’s house. He in turn gifted it to his guest, who passed it then to his son Meriones to wear, and now it was Odysseus’ head it guarded. (10.265–71)

Boar’s Tusk Helmet

We have the archaeology of Mycenaean and Dark Age Greece and many references, in the records of the mighty Hittite Empire lying to the east of Troy, to Wilusa (which gives us Ilion) and a Prince Aleksandru who ‘has a claim to the throne despite being son of a concubine’. We start to see through the Iliad to a Mycenaean world of palaces, empire and a Prince Paris Alexander who certainly went on ‘missions’ to Phoenicia (Hecuba offers the goddess Athene a Phoenician robe Paris had brought back) and whose actions in Sparta would definitely contravene Hittite regulation of client kings’ marriage treaties. This Mycenaean world has a northern trade route past Troy up through the Dardanelles/Hellespont to the Black Sea, which made Troy a valuable area to control.

Origins

We, like Pope’s travellers, can look for the real Paris Alexander of (W)ilion and reconstruct from other stories the real Helen who was crown princess of Sparta, a patron goddess in whose honour girls’ games were held in Sparta, where thousands of offerings to her have been found. We can go to Agamemnon’s Mycenae and look at Near East treaties and trade with Greece for the indications of punitive and restorative expeditions. And in Pylos we can look for the revered Nestor – with his references to exploits of when he was young, when men in those days could lift one-handed stones that a group of weaklings of today would not be able to raise; who in Book 11 of the Iliad offers Patroclus a cup reminiscent of one Schliemann found in grave circle A, shaft grave IV, in Mycenae.

Potsherd

But if we focus only on finding what is left of Troy VII (or whichever), we might miss the important questions explored throughout this book: challenges about what is recognizable, what rings true and what disturbs in a text formed over years of retellings.

In the years of re-performance by the ‘Sons of Homer’, travelling professional storytellers combining their own and others’ cycles of stories about those who went to Troy, these ‘rhapsodes’ or stitchers-together of songs, interwove other layers than of history and material culture: layers of understandings of and challenges to heroic and social values, the natural world, psychology, the cost of war and the value of human life.

Hektor, for example, defending his wife, baby and elderly parents, is set against a Paris Alexander who not only cannot be shamed but who sees from outside, unimplicated, what his fellow-Trojans are fighting and dying for. Meanwhile, Helen looks down on the battlefield, towards the two men whose fight for her should settle at least the pretext for the war. This is a Helen who reflects on her position as ‘Helen of Troy’, seemingly aware of her double-edged position as Frau Welt, as the most vilified and the most beautiful, the most fascinating while most destructive woman of all time. This battlefield is the site of heroic duels and bloody, wasteful deaths; heroes, who advance ‘glittering in armour like Zeus’ thunder-flash’, face each other ‘like opposing lines of reapers cutting swathes through some rich man’s field’, but end with chariots up to their axles in gore.

The Iliad gives us not historical and archaeological layers, sequences to be peeled away, but a weaving, finally cut from the loom and bound up in the sixth century BCE. (When it was finally ‘canonized’ and stabilized, it was for performance to Athenians trained to defend their city and fellow citizens, each man’s shield protecting his neighbour’s fighting arm, with no place for individual ‘heroics’.) The storyteller-weaver crafts the strong threads of the stories – of Achilles’ anger, of Agamemnon as summoner of forces, of Menelaus and Paris as rivals for Helen, of Hektor as Troy’s defender but also as rejector of sound advice, and of those others with stories of their own – Diomedes, the Ajaxes, Odysseus, Aeneas…

But their stories are interwoven with the dark threads of history, of Zeus’ will, of their own doom and those of the narrator’s own voice: judgments on those who go against the shape of things, the victims whose only immortality is to be their death and a brief biography recording their tragically short life and the effect on those still to hear the news.

Lighter threads are woven through: the gods, unimplicated and irresponsible; the beautifying similes that stop the action and take us to a farmstead or mountainside, from a falling body to a felled tree being trimmed to make a well-wrought, elaborately crafted chariot.

It is this setting of Hektor’s story against that of Paris; the ‘heroic values’ of a Sarpedon against those of a Diomedes; Achilles’ and Hektor’s combat within a narrative of a doomed city and a doomed man; and all against the viewpoint of those looking down with interest or indifference from Mount Olympus, that places the great set-pieces within a multi-shining texture.

Heroes and warfare: recognition and disturbance

Major-General James Wolfe, ‘the most celebrated British hero of the eighteenth century’ (National Army Museum) who martyred himself in taking Quebec, reputedly went into that fatal charge quoting Sarpedon’s address to Glaukos on the duties and privileges of a hero. Many of the classically educated young officers of the First World War took the Iliad with them into the trenches and ‘over the top’.

Perhaps conversely, Jonathan Shay, the seminal professor of psychiatry of the Veterans Improvement Program, recognizes in Achilles’ wrath many facets of the stories and psychology of those veterans he treats for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Many who turn to the Iliad see things that they recognize illuminated: grief and rage at the fracturing of values to live by and die for; the fragility and beauty of life at the edge; the strength and importance of human bonds. But others are troubled by the Iliad: by those very ‘heroic values’, its violence, the dark psychology of its heroes. Contemporary poets like Christopher Logue and Alice Oswald, among many others, have been drawn to make their own versions disturbed by some of its layers: by its attempt to memorialize, by its unsettling binding together of threads of elegy with epic.

This book is interested in reflecting on some of the universally and iconically recognizable threads – the striving for excellence, the poppy, the plight of Briseis and the women of Troy, the death of the unequivocally sympathetic Sarpedon and Patroclus, the heart-stopping grief as well as rage of Achilles – while exploring the rich, various and thought-provoking particularities of the narration in which the stories are embedded.

The process of ‘composition’ is much discussed, but has been beautifully illuminated by Greg Nagy’s image, from the Harvard Center for Oral History, of oral poetry as coming together in the same way as butter in a churn: in every rotation, more becomes solid and less fluid. Every ‘turn’ here is in performance where the ‘solids’ are the memorable scenes that the oral performer works up, to which audiences look forward: the arming scene, Helen and Priam looking down on the Greek camp from Troy’s citadel walls, Hektor saying goodbye to Andromache and his baby son, Diomedes’ day of pre-eminence (aristeia), Hera seducing Zeus, the death of Sarpedon… Each performance polishes up and may re-site these shining scenes: each performer crafts the scenes into a multi-layered whole, perhaps buffing up the patina of the antique, perhaps voicing a very modern reflection on problematic individualism or the glory of war.

The result is a various, and also variously affecting, whole.

The different parts, for instance, of Sarpedon’s great speech affect us differently:

Why do we hold the most honoured seats in our homeland; the choicest meat at the feast; the ever-brimful wine-cups? There they treat us as divine! Ours are the vast estates along the river Xanthus too, the tracts of orchard and the rich plough land. So now we must stand in the front line and lead the fight, so that the well-armed Lycians can say: ‘No ordinary men [without kleos, fame] these our Lycian kings. Theirs are the fattest sheep and honey sweet fine wines, but theirs the finest courage too.’ (12.315–21)

Here is the inspiring heroic contract, honour and reputation, acknowledgment of pre-eminence that has to be upheld on the battlefield. It is not surprising that the great British hero should quote it going to his greatest conquest – and death – at Quebec. But somehow these lines came together with a different sentiment:

Oh, my dear, if we could come through the battle and live ageless and immortal, the last thing I would do is fight in the frontline or send you into the glory-giving fighting.

And finally:

Now, as now the thousand-fold spirits of death are all around, inescapable, let us go out to either give the victory shout, or be some other’s victim.

How do these three sentiments go together? How did they sound to a classical citizen hoplite audience, told by Pericles that the greatest glory belongs to Athens, not to any individual (in a speech over Athenian war dead buried with all honour but without name). How do they sound to us?

Whatever the answers, those three sentiments sound and resound differently, and perhaps differently from each other, because of their crafting over time and to different audiences. The layers of the Iliad voice different perceptions, put different questions and at different times focalize and embed different value systems. ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Dedication

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Note

- Foreword: Why Read Homer?

- Part I: The Iliad

- Part II: The Odyssey

- Afterword: Others’ Stories, Women’s Stories: Circe, the Women of Troy, Helen, Calypso … and Dido

- Bibliography