Chapter 1

RAISING THE CURTAIN

In which we first perceived the magnitude of the storm our research had unleashed, and the crimes one industry had committed.

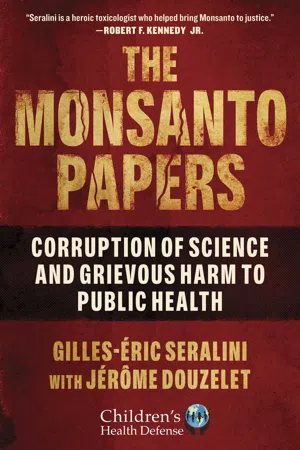

This book tells the story of a scientist who found himself in the midst of a murky and painful international criminal battle no scientist should have to endure. It is written in light of the two-and-a-half-million-page database US plaintiff lawyers obtained in 2017. Monsanto, now Bayer, one of the largest multinational producers of genetically modified organisms (GMOs), pesticides, and pharmaceuticals, was compelled through dogged use of language in the US Federal Court’s order regarding the unsealing of documents to release what became known as the Monsanto Papers.

My name appears in the database 55,952 times on 20,000 pages covering a span of fifteen years, as hundreds of people tried to discredit my research. It was unbelievable. As an academic whose research focused on this topic, I had become an expert-witness throughout the world. Beginning in 2012, thousands of reporters, public relations and marketing firms, lobbyists, pro and anti-GMO activists, victims, and politicians from around the world had seized upon what they called “The Seralini Affair.” I would have preferred if they had called it “The Monsanto Affair” or the “The Roundup Affair.” To the public, its name evokes rats with impressive tumors, photos of which have made their way around the world. But in reality, the company had been trying to destroy my reputation and my career ever since 20051 over my numerous revelations as to the hidden toxicity of its products. In the intervening years, the giant corporation was sold and lost billions in highly publicized court cases. Meanwhile, Monsanto was pushing the world’s number one pesticide, Roundup, and the agricultural GMOs modified to absorb it without dying, all in the interest of simplifying industrial farming of a single crop over a very large surface, or monoculture cropping.

It was a nightmare, as much to live through as it was to painstakingly investigate the story told in this book. Our collective health and that of our planet is at stake. But I couldn’t have gotten through it alone. This book was written with my friend and coauthor on three previous volumes, Jérôme Douzelet. He followed my research before it became public fodder, was up on the lawsuits that I filed, and the meetings with the American lawyers. He was with me through thick and thin, and even checked up on my health and that of my family. We attended many conferences together around the world in which we tackled these issues in front of thousands of people; the “Affair” followed us everywhere. For the purposes of this book, to simplify, we use “I’ here rather than “we.”

Reporters or members of the audience at talks often ask me what’s become of my life as a whistleblower and what kind of threats I received or still receive as a researcher. Why do they ask, you may wonder? There are documentaries that attempt to explain it. My first reaction is to say that I’ve never considered myself a whistle-blower but simply a researcher in the employ of the government who was doing his job, publishing his results, and, like any university professor, finding himself in need of explaining them when they reveal something new or dire. Meanwhile the threats came in all shapes and sizes, and I felt like I was living in a dictatorship.

Among my professional colleagues, I initially encountered indifference, denial, sarcasm, or my favorite, “You asked for it. You could have just reported them.” This was all small potatoes compared to the discoveries I was making: Someone was committing a crime using chemicals that were deliberately minimally and poorly tested. Through it all I was like a young horse in a storm. I kept my head down and pushed on, helped along by the unwavering support of my team even as people I met in official governmental committees whispered in my ear “your career is over.” After my talks, total strangers would threaten my family or threaten me physically. My superiors and colleagues begged me to remain calm lest I fly off the handle; members of my team were under all sorts of pressure at work.

From one day to the next a former president of the Parliament threatened to place me under investigation for fraud, an offense that could have cost me my job. And then the prime minister got involved (he’s since been exiled in Spain) and drew my infamous rats to the attention of the president of my university, the University of Caen in Normandy. Next thing I knew, industry leaders along with their shills spoke out vehemently against me in the press, attacking my person in ad hominem arguments and ignoring the results of my scientific work. I started getting pummeled with insults from the powers that be, inspired by the leadership of the Institut national de la recherche agronomique (National Research Institute for Agriculture). They accused me of groundless activism, and said my papers had all been written by other people, and therefore, should be discarded. The threats increased, and I heard things like “something bad is going to happen to you.” My Wikipedia profile was usurped by trolls and grossly falsified, quoting bloggers rather than my scientific references—not a surprise given the nature of the online encyclopedia. Even the crudest attack on my work could live on, fossilized like a footprint in the mudbanks of the scientific world: It made the undecided turn their backs, and it sowed doubt, its goal strategically blocking access to crucial funding for my work—work that could bring much-needed expertise to confront the marketing of toxic products that rake in billions. I was denigrated on social media along with my supporters, and I was even asked to resign from the University of Caen. Entire PR firms were hired for that purpose.

The French Academy of Science, without even bothering to ask the academics who worked for them, played the drumroll as one after the other they cast their cookie-cutter judgements on my case without asking me for my results or consulting me. While they were at it, they shared their opinions with the state of California, which was calling for an unprecedented vote on the subject of GMOs. I kept expecting the police to show up and handcuff me outside my lab. Already twenty-five police trucks were in pursuit of the demonstrators who took to the streets to support me during the first lawsuit I filed for defamation. My study and the photographs of the tumors in rats caused by Roundup, and the GMOs specifically modified to absorb it, had circled the world. In Russia and elsewhere, the GMO in question was banned, while in other parts, from Europe to Australia, my research was called into question by the press, by regulatory agencies, and the powers that be. What deity had I offended to provoke such a cataclysm? It’s not like I said that the earth wasn’t round, nor questioned whether man had set foot on the moon. All I had done was explain in detail the effects on our health of the most commonly used pesticide in the world, at a dose considered safe.

Exhausted and wounded to the core, like an intensive care patient on life-support, I stood my ground (I am more stubborn than most mules according to my coauthor), checking and re-checking my results, trying to block out the voices of those around me who warned me to just give up. Could it have been childish innocence to confront multibillion-dollar companies more than a little concerned by my discoveries, or the simple wish to do a good job and finish what I had started, a value inculcated in me by my parents. One thing for certain is that it stems from my desire to understand: Why cancer is so rife, along with birth defects, and lethal organic deficiencies, especially of the liver or kidneys? How can these be avoided? I was choosing to be part of something bigger than myself.

In the end, if we wanted to be as cynical as they are, we could thank Monsanto, now Bayer, for continuing their fight. Thank you for inadvertently revealing your shady operating principles not only through the Monsanto Papers, but also in the committees I served on, or even via the lobbies I fought all the way to the courts. Monsanto gives us a perfect example of how certain industry leaders, who we will uncover in the pages ahead, tried to undermine science, medicine, and public trust while they swept all critical thinking and ethics under the rug. All of this to make short term profits even as they endangered ecosystems, the climate, and world health.

We are now aware of the pure deceit with which legislation designed to protect millions of people was redirected in favor of profits and extortions, and how bloated with public funds the petrochemical industry had become. All this with the goal of getting subsidies for intensive farming, putting in place fake standards, hiding most of the toxic chemicals these products contain, and then genetically modifying crops, with the same goal in mind. Let us hope that now, more than ever, we can acknowledge a deadly precedent not to be repeated by younger generations—those young people marching in the streets to protect our climate and the planet, and to fight pesticides.

I found myself drifting away from my university. I still taught, but after this whole thing was over, I chose to continue my research with colleagues from around the world. There were several reasons for this decision. First of all, despite having excellent friends and colleagues, I could not forget the cowardly indifference I came across in meetings about the poisons being unleashed in the natural world, against our bodies and the Earth. This topic should have been of great interest in the field of education and scientific research. And then a certain few who had only published once in their lives (on the functioning of dogfish testes) started complaining about the fair division of cost of the Xerox machine. I also chose to expand the scope of my research in order to meet the most competent people around the world, and use the latest technology where it already exists, without incurring excessive costs. It’s wonderful how it leads to groundbreaking collaborations on the most pressing topics, free of national or industrial restraints and with the freedom to work independently.

It’s been quite a while now since universities have stopped funding projects of any originality, including those destined to shed light on the toxicity of products already authorized by nations. Luckily, nowadays foundations and group funding have taken their place, thanks to individuals who receive tax benefits for directing funds toward independent research. For the first time, thanks to globalization, we now have this original and fast way to improve global knowledge.

Rather than focus on vanishing biodiversity, university labs are (sometimes, not always) rife with the passivity of their leaders. Researchers are also subject to the fear of upsetting the system and of uninformed jealousies. For example, my thesis students were constantly finding themselves being tripped up as if banana peels had been slipped under their feet; they were paying for things I’d said on television that might have been awkward for the lab, always hopeful for some crumbs from industry that never materialized. My dear colleagues even went so far as to ban the press in our common spaces! They tried to dip into my private donations, earmarked to study the effects of pollution, to what end? To make up for the massive waste of the badly maintained pieces of equipment that didn’t serve any purpose anymore, lacking trained technicians to operate them or a budget to keep them running properly. I’ve seen taxpayer money drowning in waste while machinery just sat there, rust forming in its circuits. But my colleagues didn’t want to work with me or share materials or ideas on such a “divisive” topic. Out of pure jealousy, they repeated the things Monsanto said about me without questioning them.

The government was becoming increasingly silent on requests for research grants. Naturally this made it more difficult to work on exposing the toxicity of commercial products they had already approved. Without the liberty to freely post research topics, I had to relocate my doctoral students along with the technical aid they needed. At the same time my group was being invited to participate in international conferences around the world.

Meanwhile, I was publishing at least ten times more than what was deemed necessary to be considered an “active” researcher. More than ever, I needed to be able to report freely to my donors without passing through my slow-moving hierarchy. I needed to be free to fight my court battles without having to report back to people who had no interest in them, while at the same time, not subjecting them to the pressure of the lobbies. Concurrently, in order to get ahead and publish in major reviews, I had to keep up on the latest research methods being used abroad.

My increasingly astonishing discoveries forced me to remain a whistleblower. We could see the writing on the wall as early as 2005. By 2012, it had become a flashing billboard. At the time of this writing, we have unclothed the emperor and he is naked. We have come to understand the pernicious toxicity of pesticides and the GMO crops developed to incorporate them, and even more importantly, how the lobbies we had to fight were covering it all up.

Chapter 2

DISCOVERY

The genesis of the Monsanto Papers, in which we begin to get a glimpse of the Monsanto’s pseudo-science.

Lobster Omelet

January 16, 2016. I was having lunch with the American lawyers for the first plaintiffs against Monsanto at the famed restaurant La Mère Poulard on the Mont Saint-Michel, and the tide was low. The women expressed their wonder at the shifting sands that surround the island. We could hear the rhythm of a whisk beating the eggs in a copper bowl a few tables over: Someone was making one of the restaurant’s renowned omelets, in this case with lobster in it, one of the famous specialties of the historic place. My mouth watered at the aromas, my eyes feasted on the sight of all the old stone, but my throat was tight with disgusting anxiety; my research had yielded unsettling results. I already knew I would need all the help I could get from friends to support, write, and publish it.

The American lawyer, Kathryn Forgie, had come to Normandy to ask for my advice and to enjoy some time exploring the area with a colleague. She wanted to gain a better understanding of the independent studies I had performed in my lab at the University of Caen. Not an unusual meeting for a researcher such as myself. How to begin to address the possible connection between Roundup, which contains glyphosate, and its multitude of cancerous users who were claiming overexposure to the pesticide? I took as a starting point our discovery that Roundup contained hidden toxics (besides glyphosate, the better known one) and suggested she start by taking a look at the results of the tests Monsanto had already performed and documented in reports kept under lock and key. What came out of those discussions was nothing less than explosive, and the shock was felt around the world.

In March 2017 the first Monsanto Papers1 were released. They were a part of close to two and a half-million documents spanning a period from the mid-1970s (glyphosate was patented in 1974) to 2018–2019. Lawyers were bringing out new ones every week relating to different issues. The industrial giant was leaking like a sieve, a situation never before seen in modern times. There were enough lawsuits there to last a century. As Kathryn recalls: “Once the process had begun, lawyers were in their right to question Monsanto’s top brass, and request specific documents.

The company handed over millions of documents so that we would drown in them. Not only that, but some of them were flagged as confidential by the judge. Rather than identify the documents that were actually confidential (in relation to intellectual property)2 Monsanto flagged almost all of them as confidential. The lawyers had to go back to the judge to request the documents be declassified so they could be made public. The judge consented in 2017, and thus, the Monsanto Papers were born.3 Baum Hedlund, the original law firm involved in the affair, working with other law firms in the United States, took on one sick plaintiff after another. All the work was done contingently, advancing the costs and only getting paid if they won.

Thinking it was being clever, Monsanto had in fact completely opened itself up to legal scrutiny. Little by little, the press began to publish front-page stories about their almost unprecedented corruption of science, of regulatory systems, public health agencies, government officials and academies.4 Their “rotten-science” is the cause of sickness and death around the globe. I became increasingly nauseated as it became clear that the “experts” paid by the company knew all along about the toxicity of their products, but were time and again duplicitous.

Their number one priority was to falsify the scientific evidence in regulatory documents. Indeed, they hid the deleterious effects of their products in several elaborate ways. It became clear to us that these were adopted by other companies around the world. We exposed several elaborate procedures they used to fabricate their “evidence.” They didn’t stop there. In various ways, they also permanently destroyed the reputations—even possibly the lives—of researchers who discovered the toxicity. These lies were gobbled up by the press or other underlings, who whipped up fake stories up to and including the “Seralini Affair” itself. This is how I ended up at the center of this unbearable havoc, which continues to this day. It pains me to read the details of the innumerable misdeeds of these so-called “experts.” They are responsible for delaying any political decisions that might have banned toxics that daily poison not only more and more humans, but also biodiversity itself.

Our meeting with the lawyers and associates of the Los Angeles5 law firm Baum Hedlund in November 2018 shows how I became the worst nightmare6 of one of the largest international manufacturers of GMOs, pesticides, and pharmaceuticals in the world. And it didn’t stop there. In June 2019, a...