![]()

CHAPTER 1

Modernization:

A Case Study

The two decades following World War II witnessed an unflagging concern with the development of economically backward nations and depressed areas within highly developed nations. With these concerns has come an intensification of activities in the various social sciences that directs attention increasingly toward people, whether as direct human-resource inputs into productive processes, as transmitters of information and attitudes conducive to change and modernization, or as carriers of attitudes that dampen or block such processes. These developments have touched every one of the traditional social science disciplines and have also given rise to essentially new interdisciplinary specializations—among them “regional science,” “urban studies,” and a new sort of human geography. The theoretical base of the present study lies at an intersection of these various streams of thought. Empirically the focus is upon the occupational elites of the Kentucky mountains as potential carriers and diffusers of modernization, both to the mountain communities and to those of their residents (young and old) who will migrate to other parts of the nation.

Although this is a case study of one particular area, which in many respects is unique, it is our contention that such case studies are essential if we are to understand the common and the disparate aspects of development processes in a variety of socioeconomic contexts. Such indeed is the rationale of the so-called comparative method in the social sciences; if they are to be other than superficial, comparisons must derive from a better knowledge of each of the entities ultimately to be compared.

In this introductory chapter we will undertake: (1) to propose a working definition of the term “modernization,” relying upon a variety of disciplinary approaches, but at the same time posing many problems that arise from the unavoidable judgments of value involved; (2) to specify those essential environmental and other socioeconomic characteristics of eastern Kentucky that justify its selection for a case study; and (3) to delineate the theoretical sources upon which the communication focus of the interstitial person construct is based.

CONCERNING MORDERNIZATION

Economists have an initial advantage over other social scientists in defining what may be meant by “development.” They have two measures—“growth” in the aggregate (or regional) product and increase in per capita income—both of which would conventionally be regarded as objective indicators of desirable societal trends, other things equal. However, this seeming tidiness begins to crumble when we look further. In the first place the measures are not always as unambiguous as they may seem to be: this is probably better recognized by economists than by other social scientists who criticize a “too narrowly economic” view of things. A long line of thoughtful men from Sir William Petty through Adam Smith, John Stuart Mill, and Alfred Pigou to Simon Kuznets and younger national-income econometricians have wrestled with problems of what elements in the national income should be counted and how—and even with how far measured income marches in step with satisfactions or (not quite the same thing) with the quality of life.

Other problems also arise for the economist, such as the correlation of the aggregate and the per person indicators of growth in a particular case and, crucially in some instances, the “shape” of the distribution of income among a population as opposed to average or per capita values. Increasingly economists who have concerned themselves with this latter problem have emphasized the importance of what happens to the middle or (as in the case of the recent high out-migration area of the Appalachians) the bottom of the distribution of incomes. Whether as a normative goal in itself or as an indicator of solid foundations for sustained progress, a wider diffusion of income gains may be essential for development in many backward areas. Regional economic development entails diffusion of economic benefits and opportunities among the population of the area, including both individuals who will remain and those who will leave to work elsewhere.1 But development is not just an economic phenomenon.

In an earlier article, in which the concepts of regionalism and development were jointly discussed, development was defined as “the enlargement and cumulative diffusion among a population of opportunities to widen the range of experiences and satisfactions and to participate in an on-going national life.”2 The authors went on to point out that, “by this criterion, declining regions with limited economic potentials could still experience ‘development’ provided there is creatively adaptive community planning and an increase of communication with more dynamic centers.”

This view of development challenges the economist’s propensity to set aside ignorance after a few caveats, to disregard the processes by which values and tastes are formed and changed, and to neglect the importance of human interactions in socioeconomic development processes. But when measured economic ends are perceived as means to more subjectively defined ends or satisfactions (as basic economic theory would require), and when economists incorporate “spillover” or “neighborhood effects” in their models, economic development takes on broader connotations. It is then more nearly commensurate with modernization as that concept has been used by social scientists who stress the “socio” in their analysis of socioeconomic change.

Modernization, as the term is currently used,3 refers to a process of change rather than an end. This process is ultimately societal even if, as usually happens in practice, it first affects, or is activated among, an elite or another minority within a society. Types of change in the culture and socioeconomic structures of a society that are seen as progressive are termed modernization, and normally these changes are responsive to elements of change located in or emerging from a “lead” society.4 However, each society or subsociety has its own baseline configuration of established and emergent values, institutions, and resources; and it therefore both carries and combats a particular set of strains in its culture, social structure, and economy. Modernization will never be merely imitative diffusion; the adaptive changes that occur are also in greater or lesser degree creative. Because of this process, with its mixing of imitative diffusion and creativity (including creative conflict), the details of modernization cannot be specified in advance. A problem central to the understanding of modernization and basic to the theoretical and empirical analysis in this study involves identifying and understanding the interplay among diffusive acceptance, conflict, and creative adaptation—and recognizing the possibility that outcomes of this interplay can be stagnation and even retrogression as well as progress.5

For the purposes of discussion the main types of changes that may be said to characterize modernization may be conveniently categorized as changes in scale, in social organization,6 and in access of individuals to satisfying participative roles in a society. Important changes of scale include, for example, nationwide demographic growth, increases in both urban density and spread, and enlargement of the geographic areas over which there is frequent social contact (both face to face and via mass media). These changes are closely interwoven with other aspects of modernization and what it means for an area lagging in material and cultural resources.

The changes in social organization tend to be in the direction of a growing complexity in structure and in communications, with concurrent regularizing of economic and administrative processes, specialization of tasks and roles, and upgrading of skills. These can be seen as virtually unidirectional changes in society, though the speed with which they progress is related not only to the means of their diffusion but also to cultural resistances they may encounter. We would nonetheless expect that in most societies there would be a steady diffusion of changes of this type—changes that are incompatible with the persistence in their full traditional meanings of opposing values such as the familism and personalism of Appalachia.7

Inclusion of the third type of change, which we will term “social mobilization,”8 as a component of modernization is more problematic. Certain normative questions pose themselves in more or less similar fashion in all societies, whatever the particular stage of socioeconomic development. In any society, opinions will be widely divided upon our proposition that progressive social change involves the increased access of individuals to participative roles—whether this comprises increased consultation and communication across sectors of the society, or a shift in the levels of active involvement in the society’s affairs, or both. Examples of the former would be an extension of the franchise (or effective voting rights) to illiterate black people in the United States or to women in Switzerland, or a modification of attitudes leading to new forums for the legitimate discussion and resolution of group conflicts. Active involvement expands with the opening of access to previously monopolized economic opportunities through the widening of apprenticeship openings or with a thrust by newly formed elites or nonelites toward an effective voice in diverse sociopolitical activities.

Clearly, new commitments to propositions about mobilizational changes and the implementation of accompanying value choices in the modernization process present the greatest problems of conflict. While norms of sociopolitical participation are diffused from one society or subsociety to another, any changes in supporting predominant values or institutional arrangements must involve a redistribution of power, to the disadvantage of established decision-makers. Such changes will be subject to dispute according to the intensity or violence of the conflict of interests involved in a particular social context.9 The extent and nature of mobilization is a matter of peculiar interest for Appalachian Kentucky, where it may prove to be the acid test of the modernization process.

THE KENTUCKY MOUNTAINS

Whether one draws the boundaries of eastern Kentucky narrowly, to incorporate only the central subsistence-farming counties and the coal complexes at the river headwaters, or more broadly, to include some or all of the relatively more accessible counties to the north and along the southwestern edge of the eastern coalfield, he is not looking at what the modern regional scientists usually consider a region. This is not a functionally integrated economic area. On the other hand it is decidedly a cultural region with a self-conscious identity, however divided the institutions and subpopulations of that region may be.

Economic & Social Change in the Mountains

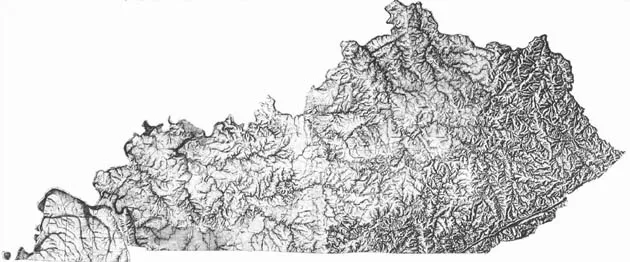

The early development of the timber and coal industries in the Kentucky mountains, although it brought employment opportunities for a wave of migrant jobseekers, never gave a stable economic footing to the mountain population as a whole. The purely physiographic characteristics of the area were decisive. Topography militated first against the laying of asphalt roads, then against the building of railways, and now against the construction of airports. The connections that were established followed the physical contours through the tortuous mountain valleys and passes (Figure 1). Railways, for example, illustrate the geographic problem. Just before World War I, lines were built up the Cumberland Valley through Harlan, from Lexington up the Kentucky River to its headwaters, and from Ashland in the north up the Levisa Fork of the Big Sandy into Pike County, at the extreme southeastern corner of the state. These rail lines were not connected with each other, and each stopped as it reached the headwaters; the system did little to cut through the internal geographic compartmentalization of the mountains. However, the railroads did bring in thousands of workers and profit seekers whose descendants have more recently been leaving the coal valleys with the decline of employment in the mines.

In 1956–1957 eastern Kentucky was just emerging from the shock of a postwar coal boom-and-bust that overlaid long-term economic problems.10 As though that were not enough, the greastest flood in the area’s recent history came in 1957. A surge of national concern with backward regions in general and with Appalachia in particular,11 similar in many ways to that of the 1930s, began at this time to stir the national Congress. In the years since, the Area Redevelopment Act, the Appalachian Development Act, the manpower acts, and the antipoverty legislation have successively been advertised with a fanfare as key measures for the Appalachian area.

FIGURE 1.

Physiographic Map of Kentucky

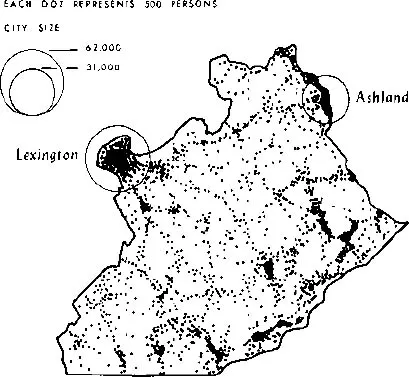

FIGURE 2.

Population Density, Eastern Kentucky Extended

Despite all this legislation the past decade has seen strip mines and huge augers piling their refuse on small hillside farms and poisoning the streams. The short-run effects have included profits but no jobs; the long-run effects are, of course, neither profits nor jobs, but the discouragement of community improvement and stultification of the tourist industry. The same decade has brought interstate highways across northern Kentucky and across the southwestern counties on the routes from Lexington to Knoxville and Chattanooga, along with the state-built eastern Kentucky Mountain Parkway—the latter being the only major road offering mountain people the possibility of greater contact with outside regions. A steady rationalization of local industry has also led to the demise of many small or inefficient manufacturing firms. Community efforts to establish or to encourage new enterprises to employ mountain people have met with almost universal disappointment and frustration, although several enterprises still hang on.12 Meanwhile the rate of out-migration has slo...