eBook - ePub

Industry in the Wilderness

The People, the Buildings, the Machines — Heritage in Northwestern Ontario

Frank Rasky

This is a test

Share book

- 128 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Industry in the Wilderness

The People, the Buildings, the Machines — Heritage in Northwestern Ontario

Frank Rasky

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Filled with photographs, both historic and contemporary, this engaging book looks at the industrial pioneers of northwestern Ontario, and the activities which brought them to the wilderness: surveying, railroading, lumber, gold, bush piloting, transportation, and hydro power. Rasky lets the pioneers tell their own story, through their own reminiscences, and by the monuments they have left behind. Published with the assistance of the Ontario Ministry of Citizenship and Culture, and the Ontario Ministry of Northern Affairs.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Industry in the Wilderness an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Industry in the Wilderness by Frank Rasky in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Geschichte & Nordamerikanische Geschichte. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

GeschichteSubtopic

Nordamerikanische GeschichteThe Goldseekers

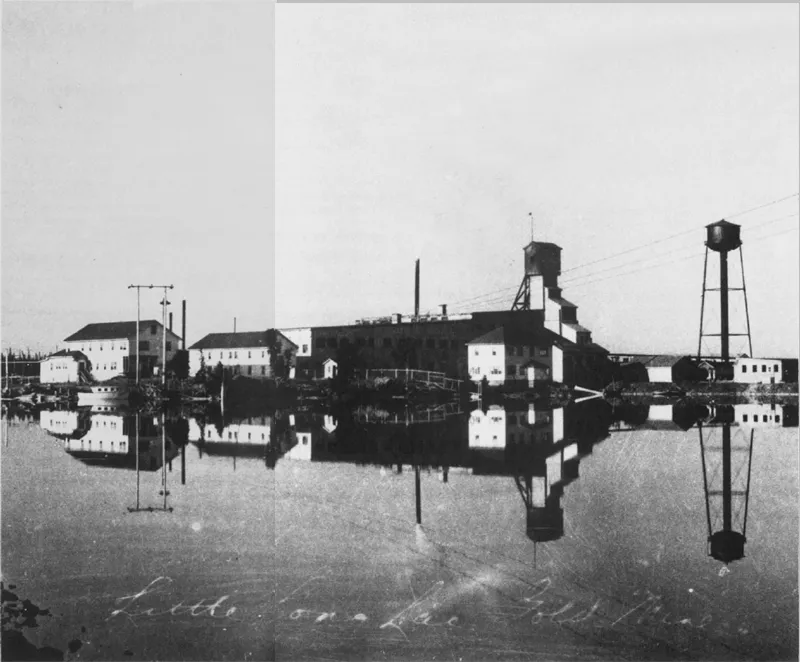

Little Longlac Gold Mine, 1930s.

The Klondike of New Ontario

Through Lac Seul they came o’er the Ear Falls terrain

Up the Chukuni to Pakwash and Snake,

To Twin Island Lake, through Gullrock and Keg

To the waters now known as Red Lake.

Then lo and behold, the discovery of gold

Brought people by hundreds to prospect and stake,

Planes flew day and night, a prospector’s delight,

And boats almost covered the lake ...

“The Ballad of Red Lake” by Robert O. Stark

“Look at this visible gold!” said excitable Lome. “Looks like we found it!”

“Ain’t that what we come for?” said taciturn Ray. “Just take a look at mine.”

With that exchange of dialogue, the brothers Lome and Ray Howey ushered in what was billed at the time as the Klondike of New Ontario. It was 25 July 1925, and the pair of amateur prospectors from Haileybury had spent the past two weeks on a futile treasure hunt. They had chanced upon a geological report from the Ontario Department of Mines. It hinted of gold-bearing quartz veins evidently visible in the greenstone layers of Precambrian rock on the shores of Red Lake, 2011 kilometres northwest of Toronto.

With their picks and pans they had searched vainly the southeast end of the lake — a lobster-shaped, reddish muddy body of water, 40 kilometres long, three kilometres wide, extending claws into 250 kilometres of indented shoreline — and were ready to give up. But then a bolt of lightning literally helped them make a lucky strike. It struck a spruce tree which toppled not far from their camp.

Before leaving, the two brothers decided to make one last try, each from a different direction. Thanks to the uprooted tree, they stumbled upon exposed outcroppings of quartz glittering with yellow filigrees of gold. “I was so happy,” Lome later said, “I could have wept with joy.”

He confided the secret to Jack Hammell, a breezy former prizefighter under the boxing ring name of “Whirlwind Jack,” who had become one of the shrewdest mining promoters on Bay Street in Toronto. Invited to come up and examine the lucky find himself, Hammell performed like a whirlwind. He promptly staked out additional claims for the Howey Syndicate, and got a promised $500,000 backing under option from the rich Dome Mines of Porcupine. The word leaked out, and in January of 1926 the stampede was on.

Ultimately an estimated 8000 greenhorns and sourdoughs were infected with Red Lake gold fever. They scrambled to stake more than 10,000 claims in lake-pocked, swampy and granitic gold fields stretching from Favourable Lake on the west (which proved to be most unfavourable) to Pickle Crow on the east (as quirky as its name and as erratic as its promoter, Jack Hammell, but which eventually produced $35 million).

Altogether, since the original Howey discovery, fifteen productive mines in the Red Lake region have yielded $800 million worth of gold bullion. Of that total, the present Campbell Red Lake mine, ranked as the richest producer in North America, has been responsible for $500 million alone.

But the last of the great gold rushes was significant not merely because it was a financial bonanza. It gave rise to innovations in the milling of hard rock gold and transporting heavy equipment in the north country. It cradled commercial aviation in Canada and parented the whole field of bush piloting. And, in the phrase of that master promoter, Jack Hammell, it “cracked open the north.” It drew world attention to the mineral potential waiting to be wrested from the bush country in the far reaches of the Canadian Shield.

A headline in the Boston Post in 1926 blared: “‘Mush On’ Goes Out the Cry — While Yet Another Impatient Prospecting Party Hits the Trail for Red Lake.” From the four corners of the earth they came to mush to the new Klondike. They seemed to be seized with an uncontrollable wanderlust, abandoning wives, jobs, orderly lives, for what purpose?

“I think many of us were romantics, seeking the escapism glamourized by Jack London and Robert W. Service,” says Don Parrott, who admits to being influenced by both. Now retired at 67 after close to half a century of prospecting in the bush country, the Winnipeg-born author of The Red Lake Gold Rush sits in his modest apartment in Thunder Bay beside the railway tracks. He browses through his scrapbooks of yellowing news clippings and faded snapshots, and reminisces about the great adventure of his life.

He believes it took a certain kind of dogged, strong-minded individualist to persist in scrabbling for hard-rock gold. He thinks many of his fellow Red Lakers had the traits of the wild brier rose that thrives tenaciously on the granitic Canadian Shield.

Dog teams hauled people and goods along snowy trails to places that were inaccessible by plane or boat.

The Café Hotel, and the Red Lake Laundry were town landmarks in 1920.

Prospector John Jones, third from right, posed with a group of Indians for a picture taken in Red Lake, 1925.

A lone inhabitant wanders along MacKenzie Island’s rolling Main Street in the early 1940s.

This “Duck Walk” crossed the swamp in the foreground over to Howey Mine. In front of the mine are the Catholic Church and the Provincial Police Station.

“Call us eccentrics, if you will,” said Parrott, a lean, flinty man, with a liking for cowboy boots and bright shoelace ties, a rat-trap memory for geological details, and a passion for preserving Canadian history. “But whatever you call us, you’ll have to grant us a lot of colour and character. It sometimes seemed that everybody who settled in Red Lake was a bigger-than-life character. And God knows, plenty of us were naive characters, when we set out to mush north up the Red Lake trail.”

The trail began in Hudson, a whistle stop at the end of steel named after a builder of the Canadian National Railway. In January of 1926, this pinprick of civilization in the virgin bush was invaded by the first wave of stampeders. They were a motley rabble, bearing picks and pans and 40-kilogram packsacks, but most of them woefully unequipped for the gruelling, five-day trek over frozen lakes and rivers to Red Lake 85 kilometres north.

“Some journalist said the slogan on everyone’s lips was ‘Red Lake or Bust.’ But I’m willing to go on record that it was ‘Mush, you S.O.B.’s!’” That was the vivid recollection of Gordon Shearn, an immigrant from Bristol, England, who was deafened by the bedlam in Hudson. “Every train was loaded with gold seekers, many suffering from a bout with John Barleycorn,” he wrote. “The din of dogfights, drunks, howling dogs, whistling trains and roaring planes made Hudson the noisiest town on earth. It was hard to find a tree stump without a dog attached to it.”

He didn’t dispute the estimate, of another journalist that the trail to Red Lake was blazed with 3000 dead husky dogs. But he doubted whether the mutts pulling the sleds were genuine husky dogs. Huskies were in such short supply that they were fetching up to $200. Consequently, entrepreneurs were cleaning up, it was said, by dognapping bulldogs and fox hounds from as far away as Winnipeg and selling them to greenhorn prospectors at premium prices.

Shearn got up the nerve to hire himself out as a professional dog team driver. Eventually, he wound up with $100,000 by staking Red Lake’s other present producer, the Dickenson Mines Ltd.

He was luckier than Hans Pokolm, a bumbling greenhorn from Gdansk, Poland, who walked all the way up the Red Lake trail with another Polish newcomer, Otto Reinfandt. “We had no map, no compass, no parkas, and we were carrying two suitcases each,” Pokolm recalled dolefully. They wore ordinary overcoats and had one pair of snowshoes between them — which they didn’t know how to use. “We put on the snowshoes backwards — I never saw a pair before in my life — so after a while we carried them, too, because as soon as we’d take two or three steps, we’d take a header into the snow.”

They finally stumbled upon a huddle of tents and shacks and asked a man how far it was to Red Lake. “This is it,” he said. “That’s all there is.”

“My God, I can never tell you the disappointment I felt,” Pokolm later recalled with amusement. “When I left my little village in Europe, I dreamed of picking up nuggets of gold off the streets like hen’s eggs. Instead, I found a couple of shacks, a frozen lake, wolves, everything buried in snow. And far from there being gold in the streets, there were no streets! The hard-rock gold you had to dig deep out of a mine only ran about five dollars’ worth to one ton of ore.”

Nevertheless, Pokolm zealously joined the throngs of newcomers staking claims optimistically named “Big Lode,” “Rajah,” “Zeus” and “Red Lake Tiger.” Only veteran prospectors were able to get a chuckle out of the claim named “Sanshaw.” It was an inside joke, signifying that the staker was going ahead with the diamond drilling and sinking of a shaft, though the mine did not have the blessing of John Shaw. He was the Nova Scotian mining engineer, so severe in his appraisal of a mine’s potential that he was nicknamed “Turn ’Em Down” Shaw. (One claim that did win his approval was the McKenzie Red Lake mine, from which, according to his son, Toronto engineer George Shaw, his late father made “a tidy sum.”)

Though the majority of stampeders did not strike it rich, they earned themselves some picturesque names. Parrott recalls that there were four Bill McDonalds in the Red Lake gold camps, and to distinguish between them, miners nicknamed them “Windy Bill,” “Cranky Bill,” “Happy Bill” and “Squeaky Bill” McDonald.

The nickname that most tickled Parrott was the one awarded to a promoter named George S. Clark. “He was a good talker, and when buying and selling claims, was admired as a champion bull-shooter,” says Parrott. “So everybody called him B.S. Clark instead of by his initials of G.S. He was so widely respected under that monicker that Clark himself proudly signed his cheques with a ‘B.S.’ “

To Murray (The Hairy One) Watts, who recently died, aged 72, probably the best-known of the stampeders, the heroic figures of Red Lake were its prospector-promoter pugilists. “They had the real pioneer spirit, wouldn’t be beaten by the odds, and used their wits as well as their fists,” he said shortly before his death in October, 1982. It is a pretty good summation of Watts himself. A modest millionaire, he had retired to his hometown of Cobalt, after an illustrious career in mine exploration across the Canadian Arctic that began 55 years ago in Red Lake.

He was then 17 and visited the region’s gold camps as an apprentice prospector for a mining syndicate. Later, in the mines he explored from Ungava to the Coppermine, travelling via canoe and dogteam, the Eskimos named him Merkooleek, meaning The Hairy One. But his boxing skill had already won him the nickname of The Cobalt Kid, and he was thrilled at the prospect of meeting his prize-fight idols who had rushed to stake claims at Red Lake.

There was Jack (The Nova Scotia Kid) Munroe, former mayor of Elk Lake, Ontario, and heavyweight boxer. He won knockout bouts with the mat king, Kid McCoy, and laid out world heavyweight champion Jim Jeffries for the count of nine in Butte, Montana in 1903. Though...