- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

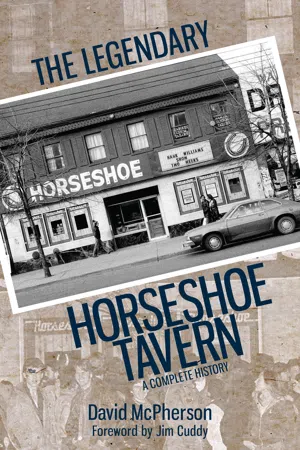

A complete history of Toronto's legendary Horseshoe Tavern, "the Birthplace of Canadian Rock," to coincide with its seventieth anniversary.

Like the Queen Street strip that has been its home for seven decades, the Horseshoe Tavern continues to evolve. It remains as relevant today as it did when Jack Starr founded the country music club on the site of a former blacksmith shop. From country and rockabilly to rock 'n' roll, punk, alt/country, and back to roots music, the venerable live music venue has evolved with the times and trends — always keeping pace with the music.

Over its long history, the Horseshoe has seen a flood of talent pass through. From Willie Nelson to Loretta Lynn, Stompin' Tom Connors to The Band, and Bryan Adams to the Tragically Hip, the Horseshoe has attracted premier acts from all eras of music. In The Legendary Horseshoe Tavern, David McPherson captures the turbulent life of the bar, and of Canadian rock.

Like the Queen Street strip that has been its home for seven decades, the Horseshoe Tavern continues to evolve. It remains as relevant today as it did when Jack Starr founded the country music club on the site of a former blacksmith shop. From country and rockabilly to rock 'n' roll, punk, alt/country, and back to roots music, the venerable live music venue has evolved with the times and trends — always keeping pace with the music.

Over its long history, the Horseshoe has seen a flood of talent pass through. From Willie Nelson to Loretta Lynn, Stompin' Tom Connors to The Band, and Bryan Adams to the Tragically Hip, the Horseshoe has attracted premier acts from all eras of music. In The Legendary Horseshoe Tavern, David McPherson captures the turbulent life of the bar, and of Canadian rock.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Legendary Horseshoe Tavern by David McPherson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Music. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

3

Tom’s Stompin’ Grounds

Come all you big drinkers, and sit yourself downThe Horseshoe Tavern waiters will bring on the roundsThere’s songs to be sungAnd stories to tellHere at the hustlin’Down at the bustlin’Here at the Horseshoe Hotel— Stompin’ Tom Connors, “Horseshoe Hotel Song,” from the gold record Live at the Horseshoe (1971)

Drifter, outsider, larger-than-life, and patriotic to the core — there was no one else like Stompin’ Tom Connors.

Many consider the musician to have been a national treasure. His catchy songs with simple lyrics, which are easy to memorize, are still sung from coast to coast by generations of Canadians. Who doesn’t know the refrains to his timeless tunes such as “Sudbury Saturday Night,” “Bud the Spud,” or “Big Joe Mufferaw,” about everyday characters who embody the spirit of our country? Mark Starowicz captured the essence of Tom’s patriotism in a feature for the Last Post in 1971:

I never thought that nationalism was so deeply ingrained in this country until the first time I saw Connors at the Horseshoe. I’ve seen a packed crowd go wild over a singer before, but I’ve never, never seen so much unrestrained joy and applause as when this rumpled Islander got up and started strumming.

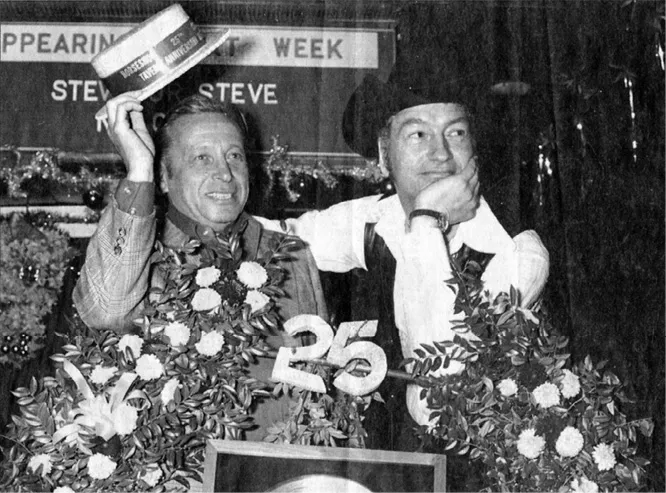

Jack Starr (left) celebrates with Stompin’ Tom Connors on the occasion of the Horseshoe Tavern’s twenty-fifth anniversary in 1972.

As the 1960s started to set, making way for the 1970s, the country singer from Skinners Pond, Prince Edward Island, made up his mind that he wanted to perform at the Horseshoe regularly. So he kept coming in and asking Starr to give him a chance. Again and again he’d get his courage up, only to have it knocked down by Starr. But eventually the young musician’s persistence paid off. Jack Starr saw something others didn’t in the fellow outsider.

Today, Connors’s legacy is as legendary as the tavern itself. You could say, for a while, it became Tom’s bar. “Tom made a big mark in that place,” recalls Johnny Burke.

As this chapter unfolds, it will become clear that those eight words of Burke’s are definitely an understatement. Dick Nolan’s biographer, Wayne Tucker, shares the following anecdote that foreshadows Connors’s lasting legacy:

Willie Nelson played the Horseshoe in the 1960s, backed up by the Nolan-led Blue Valley Boys. Dick was around Willie every night and they raised a few glasses together.

The Blue Valley Boys — circa mid-1960s — who were the house band at the Horseshoe, backing up all the Grand Ole Opry stars. From left: Roy Penney, Bunty Petrie, Dick Nolan, Johnny Burke.

One particular time Dick and Willie were chatting over a beer while another performer who was an unknown at the time was on stage. Dick noticed Willie’s mind was drifting and he kept looking up at the singer. Willie said, “Dick, that guy’s got somethin’ goin’ for him. He’s gonna turn out to be somebody.”

And “somethin’ goin’ for him” he sure did have. Stompin’ Tom went on to set attendance records at the ’Shoe that still stand today, more than forty years on. He recorded a gold record (Live at the Horseshoe) and filmed a feature concert film (Across This Land with Stompin’ Tom Connors) in the bar’s cozy confines, and his record of playing the bar for twenty-five consecutive nights is one that is likely never to be broken. Journalist Peter Goddard, who covered many of the musicians and shows at 370 Queen Street West starting in the early 1970s, provides his take on Tom’s Horseshoe legacy: “If anybody could be said to embody the old and the new, the punk of the Horseshoe, it was Stompin’ Tom. He was louder than any punk band. He came at you like a sledgehammer, which was perfect for the place. He was the real thing.… He also foreshadowed a lot of the punk bands that later tried to emulate him. If the Horseshoe ever reached the nadir of its identity it would be with him.”

Connors’s legacy was solidified at Starr’s tavern. As with many Canadian musicians who came after him, the Horseshoe helped boost his career. “These people really like you, Tom,” Jack Starr told Stompin’ Tom in 1969, one year after Starr gave Connors his first gig. Those genuine words of gratitude came only after Canada’s version of the outlaw country singer — who did not fit the mould of the Grand Ole Opry stars who had graced the stage over the previous decade — had proven his worth and gained the Horseshoe owner’s admiration.

The late 1960s ushered in a new era at the Horseshoe Tavern, and Stompin’ Tom led the charge. Like Starr, Tom was an outsider. Bands had a hard time keeping up with his stompin’ foot and his offbeat rhythms. His songs spoke of blue-collar characters: drifters and dreamers like him. That’s why his stompin’ sounds and often silly sing-a-long lyrics resonated with the Horseshoe’s loyal patrons, since the majority of Starr’s regulars came from Connors’s corner of the world: Atlantic Canada. Beyond his fellow East Coasters, Tom would draw a diverse crowd, a motley mix of beer-drinking regulars — from Toronto Maple Leafs fans, to college students, factory workers, and farmhands, to plainclothes police officers. Tom would sing a corny song filled with off-rhymes about Kirkland Lake, Sudbury, or another rural Ontario town, and the Horseshoe’s patrons would holler, hoot, and pound the tables.

“Tom created a conversation,” recalls Mickey Andrews, who played pedal steel with the Canadian icon for years. “He would always have a song about a town that someone from the audience could relate to. He had a different way of entertaining them, drawing out their animal instincts. They weren’t rowdy, but they were boisterous, and the air was electrifying.”

Stompin’ Tom Connors got his moniker due to his penchant for pounding the floor with his cowboy boot, keeping time. These stomps were so heavy that they started to wear out the carpet and floorboards everywhere he performed. Eventually, Tom came up with the idea to put down a piece of plywood — a stompin’ board, which he bought at Beaver Lumber — down on the stage before each show. As he stomped, dust and chips flew into the air. This was all part of the legend in the making.

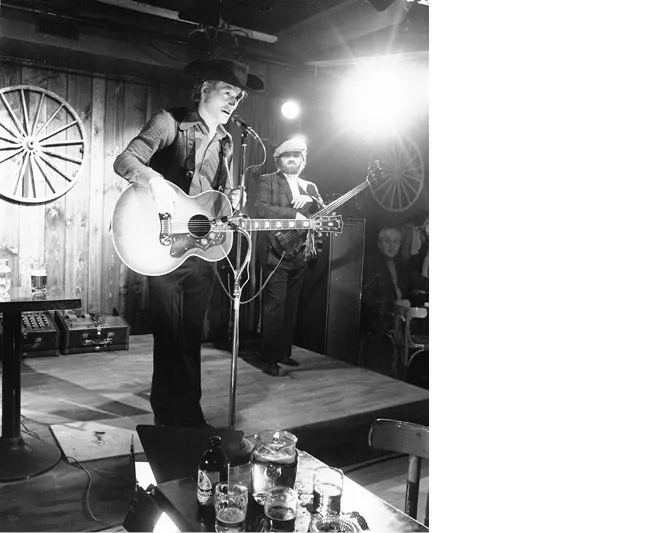

Stompin’ Tom Connors — who still holds the record for the most consecutive nights played at the Horseshoe Tavern — seen here in a still photo from the movie Across This Land.

The country singer from Canada’s smallest province came to the club owners and concert promoters like a thirsty lion, not a shy lamb. Tom was always his own best PR person; the way he landed the gig at the Horseshoe is a perfect example of this dogged determination. Andrews recalls seeing Tom play at an after-hours club before Starr hired him, and thought he was tipping off the club owner to a new act. Not so. Tom had already gathered up his courage and been to see Starr many times, begging for a chance to play that storied stage. In late 1968, Starr finally relented, giving Connors a chance to prove himself by booking him for a one-week stint. It’s something the late musician never forgot. In his memoir Stompin’ Tom and the Connors Tone, the singer devotes an entire chapter, “Landing the Horseshoe,” to Starr’s bar. In it, Connors recalls the seminal moment when he signed his first contract to play the iconic institution on Queen:

On the twenty-eighth or twenty-ninth of November, I got my courage up again and decided to go down to Toronto and try the Horseshoe Tavern, only this time minus the suit. I really didn’t have much faith in landing a job there because the Horseshoe was known all over Canada. Everybody who was a country fan and who landed in Toronto for any reason, either by plane, car, bus or train, for any length of time, sooner or later, wound up paying a visit to the Horseshoe. The owner’s name was Jack Star [sic] and he had kept the place “country” through thick and thin now for over twenty years and the club had a great reputation. There wasn’t hardly a weekend that went by that the place wasn’t packed, due mainly to the fact that he would always bring a big-name act from Nashville, Tennessee, to play Friday and Saturday night. When Jack finally arrived on the scene I was pleasantly surprised to find that he was a very quiet, congenial man, even though he had the demeanour of a person who knew his business very well. He made me feel at ease and I began telling him what I had done, where I had been up until now, and just how much I wanted a chance to play his club to see how well I could fare. “Well,” he said, “I’m trying out a new house band next week and if you want to come in and see if they can back you up, I’ll give you the opportunity to see what you can do. Bring your contract in before you start on Monday night and I’ll sign you on for a week.

Tom could not believe his ears. That weekend he went back to where he was staying, and that’s all he could talk about with the owners of the house. On Monday, at around four o’clock in the afternoon, he returned to the Horseshoe and just sat there for the next five hours, until his set time at 9:00 p.m. The only interruption to his thoughts came when Starr stopped by his table and asked him for his union contract. After signing it, Starr shook Connors’s hand and said, “You must really want to play here. I’ve been watching you sit there for the last three or four hours, and I don’t think you took your eyes off the stage once.”

That first gig established the tone and set up Tom for his legendary run at the Horseshoe. Tom was relaxed and ready to give it his best shot. “This gig is going to be a snap for me,” he said, “because every place [I] had ever played up until now, [I] had to carry the whole ball all by [myself].” At other bars, Tom was used to starting at 8:00 p.m. instead of 9:00, and he would do four one-hour sets, with only a fifteen-minute break after each hour, before finishing up at 1:00 a.m. At the ’Shoe, he had to play for only an hour and a half during the whole night.

From the time he dropped his famed stompin’ board on the stage and started to sing, he never looked back. Initially, the boys in the house band found it difficult to keep time with Tom, but as soon as they realized his left heel was always coming down on the offbeat, rather than on the downbeat, they quickly grasped what was going on and started to have almost as much fun watching Tom as the audience did. Connors recalls the reaction on that memorable night: “Even the waiters who had been there for twenty years or more were seen from time to time to just be standing there wondering how in the hell could I stand on one foot for so long and go through the antics I did without falling down.”

In between sets, Tom used the time to do what he did best: public relations — consuming a beer at every table, talking to everyone, and selling his records. By the time the night was over, the musician knew every patron by his or her first name; he then stood by the front door, as if he owned the place, thanking them for coming as they left.

By the end of that first week, word had spread along Queen Street and out into the suburbs. Many people came back to see the show on the weekend and brought their friends. Even though the place still wasn’t packed, Stompin’ Tom managed to get another contract signed with Starr — this time not just for one week, but for three.

For Tom, the chance Starr gave him that November and the faith he placed in him was the best gift he ever received. It’s also one he never forgot. “This all took place about the first week of December in 1968,” he recalls in his memoir. “It gave me the extra money I needed to buy Christmas presents for everybody, but the best Christmas present of all was the one I got. And that was my opportunity to play the Horseshoe Tavern in Toronto for the first time.”

The following February, Tom returned to the Horseshoe, backed by a new house band. Apparently Jack Starr was trying out different bands at that time, trying to find one he was happy to hire full-time. That return to the ’Shoe for Tom was not what he had expected, because he didn’t click with this band as he had with the one he had played with the previous November. Connors reflects on this lack of chemistry:

From my very first night on the stage, I could see the guys in this band were either very jealous of me, or they just didn’t appreciate what I was trying to do. I was singing my own songs, of course, and doing absolutely nothing from the current hit parade. This they didn’t seem to understand. For the whole week they didn’t talk to me and just kept screwing up my songs whenever they could in an effort to discourage me and get me to quit. During each break they’d just go to a back table and sit by themselves while I was always associating with the people. And practically every table I went to, they’d tell me how the band kept sneering, laughing and pointing at me behind my back in an effort to get the audience to do the same thing. Unfortunately for them, their little scheme wasn’t working. I just ignored the whole thing, did the best I could under the circumstances, and kept right on with my public relations.

At the end of Saturday’s matinee, Starr called Tom into his office and asked him how he liked the new band and how they were getting along. Connors, ever diplomatic when he needed to be, knowing how tough it sometimes was for musicians to get work and not wanting to lessen their chances of keeping their jobs in any way, told Starr that while they did seem to be a bit standoffish, it was probably due to shyness, and while they hadn’t quite caught on to his music yet, they would probably get used to him and do a lot better job next week.

Starr wasn’t fooled. He knew the truth. The tavern owner replied, “Well, Tom, that’s all very decent of you, but you don’t have to give me any crap. These guys have been into my office three times this week trying to get me to let you go. They said you can’t keep steady rhythm, you’re annoying the customers, and your foot is driving them crazy.”

As Starr sat staring at him from behind his desk, Tom tried to defend himself against these allegations. Before long, Jack interrupted him and eased his mind: “Don’t worry yourself about it. I’ve been keeping tabs on the whole situation, and after tonight, you won’t have to work with these guys anymore. I’m keeping you and letting them go.”

Starr then asked Tom how he had gotten along with the previous band he had played with. Tom told Jack he thought they were excellent and that they had all gotten along very well. The good news was that Starr still had that band on standby, and he assured Tom they’d be backing him up the following week and any time he played the Horseshoe thereafter. Then Starr flashed his infectious smile, got up from his desk, shook Tom’s hand, and said, “These people really like you, Tom. Now go and get ’em.”

That band that Tom played with when he returned to the ’Shoe the following Monday had just seen Clint Eastwood’s latest western The Good, the Bad and the Ugly and decided it was a perfect moniker for their trio: Cape Bretoners Mickey Andrews on pedal steel and bassist Randy MacDonald, along with Newfoundlander Gerry Hall on lead guitar. These three musicians were the Horseshoe’s regular house band up until the mid 1970s, shortly before Starr retired from the business in 1976.

In those days, the Horseshoe could seat between 300 and 350 people. By Tom’s third week of regular gigs, the place was packed even before the Nashville guests arrived on Saturday night. Most of the customers were from Newfoundland or the Maritimes, but Tom started to draw lots of patrons from all over Ontario and from western Canada. Tom continued his public ...

Table of contents

- Praise

- HTP

- TP

- CR

- Ded

- Epi

- Contents

- Foreword

- Intro

- CH1

- CH2

- CH3

- CH4

- CH5

- CH6

- CH7

- CH8

- CH9

- CH10

- CH11

- Aft

- Ack

- Sources

- Image Credits

- AbouttheAuthor