![]()

Chapter One

Getting to Know Steven Truscott

June 9/1959

6:30 p.m.

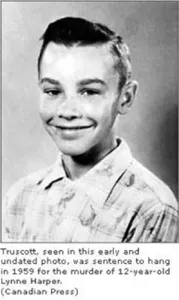

Steven Truscott leisurely biked around the grounds of Air Vice Marshal Hugh Campbell School—the main academic institute for young children whose parents worked at the Royal Canadian Air Force base in Clinton, Ontario. It was a humid night—Clinton was in the middle of a heat-wave and it hadn’t rained in a month. Truscott wiped his brow and vaguely thought about going swimming or fishing. A good-looking 14 year-old boy, Truscott had brown hair slicked down in the style of the day. He wore red pants and had a green bike. Tall for his age, Steven exuded the confident air of an adventurous teenager who loved sports and being outdoors. The previous November, he led his school football team to victory in a competition called the Little Grey Cup.

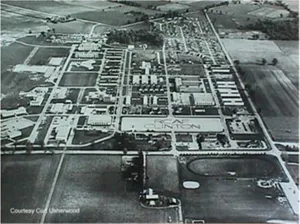

There were no planes at this RCAF installation; it served as a teaching center, where air force men and women studied radar, radio, meteorology, and telegraphy, among other disciplines. The base was located a few kilometres from Clinton, a small, conservative community in southwestern Ontario. Three hours west of Toronto and minutes away from Lake Huron, Clinton was a dry town, with no beer or liquor stores.

At its peak, the RCAF base accommodated 3,000 personnel. Among their ranks was Truscott’s father, Daniel, an RCAF warrant officer. His mother Doris largely devoted herself to looking after her boisterous family, which included first-born son Ken (who was 16) and two siblings, Bill and Barbara who were younger than Steven. The family lived at 2 Quebec Road in the Permanent Married Quarters (PMQs) on the base. The PMQs was a community within a community for RCAF members with families. Single enlisted RCAF personnel had to make do with barracks.

While Steven Truscott was popular with his peers, he was wary about getting too attached to any one set of friends. As an army brat, he had moved with his family from base to base across the country, at the direction of army prerogatives. The Truscott family had been living at RCAF base Clinton since the summer of 1956.

Truscott was due back home at 8:30 p.m., to babysit his little brother and sister. In the meantime, he took advantage of the unseasonal warmth by roaming. Most of the other kids in the base PMQs had the same idea, and the evening air was filled with the sounds of children at play. Adults also enjoyed the fine weather, firing up barbeques or just sitting outside, cold drinks in hand.

Truscott continued his somewhat aimless rambling. He biked away from A.V.M. Hugh Campbell School, towards the county road, the main thoroughfare in the community. The paved, two-lane county road led north from the RCAF base. The road bordered the property of Bob Lawson, a local farmer. He owned 150 acres of farm and brush directly east of the county road. Bob was a genial man and local children liked to hang out at his property, to play and watch the farm animals. Kids also frequented a wooded patch called Lawson’s Bush set on the northern end of his property. Lawson’s Bush could be directly accessed from the county road by a rough lane known colloquially as the tractor trail.

“The Lawson’s were really nice to us,” Joan Tyre recalled, decades later, in a police interview. “We were like their kids. We could go and look at the cows. They had a big barn, and they had a radio up there, so we’d go and listen to all the latest dance tunes. It was just fun.”

Like Truscott, Tyre grew up on the RCAF Clinton base in the late 1950s.

Several hundred feet past Lawson’s Bush, the Canadian National Railway tracks crossed the county road. And just a short distance from the tracks was the Bayfield River, which was a popular spot to swim and fish on hot days. The county road followed a bridge over this river and led to King’s Highway 8. To the west, King’s Highway 8 led to Clinton. To the east, it led to the town of Seaforth.

Truscott was seen biking around the bridge over the Bayfield River by a handful of people, including Beatrice Geiger, an air force base mom out for a bike ride of her own. At some point, Truscott bicycled back to the school grounds, where a pack of Brownies were having a scavenger hunt. Truscott causally watched the Brownies, in no great hurry to get home. A young girl named Lynne Harper, who had been chatting with one of the adults supervising the Brownies, noticed Truscott, and sauntered over. At 12 years-old, Harper was a petite (five foot three, 100 pound) schoolgirl in the same mixed grade seven and eight class at A.V. M. Hugh Campbell to which Truscott belonged. Her family also lived in the PMQs section of the RCAF base. She wore turquoise shorts and a white blouse.

Harper walked up to Truscott, who stood by his bike, and began bantering with him. She sat on his front bike tire as they causally made small talk. At some point, the girl made a request.

“I was going towards [the Bayfield River] to see some of the boys who were going fishing,” Truscott recounted later in a statement to police. “She asked if she could have a ride down to the highway.”

Truscott said sure, and the pair strolled away from the playground. Truscott, who was walking his bike, looked inside a kindergarten classroom and spotted a clock, which read 7:25 p.m. Once the pair reached the county road, Harper seated herself on the crossbars of Truscott’s bike and he gave her a ride to the highway.

Truscott said Harper asked him about a little white house outside of town where a local recluse lived. The recluse raised ponies and local children liked to go to his house and look at them. Harper seemed in a buoyant mood, even if she admitted to quarrelling with her parents, recalled Truscott.

“She said she was mad at her mother ‘cause she didn’t let her go swimming. That is all she said on the way down. She wasn’t mad. She was care-free. It took about three or four minutes. She just asked if she could get off and she got off and I went back to the bridge,” Truscott told police.

Truscott estimated he dropped her off around 7:30 p.m.

He said he stopped on the bridge to look back at his passenger. He noticed that Harper was hitchhiking by the side of the highway.

“I just turned around to see if she had a ride yet and a grey Chev picked her up. She had her thumb out. A car swerved in off (the) edge of the road and pulled out,” stated Truscott.

The vehicle stopped on the side of the highway, giving Truscott a good opportunity to examine it. He noticed “an odd licence plate” on the vehicle, which he further identified as a 1959 model. The plate in question had a yellow background. Like many teenage boys, Truscott was a car buff. He cited several pertinent details about the Chevrolet in his police statement. The car had “quite a bit of chrome, white wall tires … it was something like a Bel Air,” read his statement to police.

According to Truscott’s police statement, Harper “got in the front seat and the car pulled away, going towards Seaforth … I just stayed down at the bridge and watched boys swimming then went back to the school. Boys were (Arnold) George, (Doug) Oates, (Jerry) Durnin, (Garry) Gilks (sic). On the way down I waved to (the) boys. On way back I waved at Arnold George, a school chum. I stopped for about five minutes. The boys were about 150 feet away … I stayed at the bridge about five minutes. I didn’t see the car again. I looked at (the) highway once and didn’t see anything.”

Truscott proceeded to bike home, past the school grounds where some kids were still playing. Truscott got off his bicycle and mingled with the boys, whose ranks included Ken, his older brother.

Eleven-year-old Stewart Westie, a grade seven student at the school, was one of several children who saw Truscott upon his return. Westie was playing baseball that night and importantly, was wearing a watch.

“I saw Steve and Lynn (sic) about 7:30 p.m. but I would allow 20 minutes either way,” read Westie’s statement to police. “The first I saw them they were walking between the white fence and the school, Steve pushing the bike and Lynn (sic) walking beside him. They walked up past the school and right up the county road just above the bend, and then Lynn (sic) got on the bike and Steven got on and they rode in the direction of the river. I didn’t see them talking. I just turned and saw them going up. We were playing baseball. About half an hour later Steven came down the road on his bicycle alone … one of the boys called to him, ‘What did you do with Lynn (sic), feed her to the fishes?’ and Steve said, ‘No. I just let her off at the highway.’”

More teasing followed, then Ken reminded his sibling that it was his turn to babysit. Ken, who was riding Billy’s bicycle, suggested that he and Steve change bikes. This was done, and Truscott rode home, on his younger brother’s bike. He got in around 8:25 p.m., according to his mother who was chatting with a neighbour. It was still remarkably warm and light out. The sun would not set until 9:08 that evening.

Truscott’s parents left the house shortly after their second-born son arrived. Steven checked the refrigerator to see if there was anything good to eat. He selected some food then prepared for an uneventful evening of babysitting.

![]()

Chapter Two

Getting to Know Lynne Harper

Flying Officer Leslie Harper, his wife, Shirley, and their three children, lived on 15 Victoria Boulevard in the Permanent Married Quarters (PMQs) of RCAF Station Clinton. Their 12 year-old daughter, Lynne, was the middle child in the family. Born in 1946, her full name was Cheryl Lynne Harper. In June 1959, she had a 16-year-old brother named Barry and a five year-old brother named Jeffrey.

The Harper home had a large lawn and was shaded by trees in both front and back. The lawn was kept orderly and trim (army regulations demanded frequent mowing and maintenance). Clean-cut Lynne was active in Girl Guides and enjoyed helping around her home. Her mother had rheumatism in her hands, so Harper frequently assisted with household chores. By all accounts, Harper was eager to be liked and accepted.

Until You Are Dead—author Julian Sher’s brilliant account of the Truscott story—quotes one Maynard Cory on this aspect of Harper’s personality. Cory was the proprietor of a convenience store on the RCAF base that was patronized by kids in the area.

Cory described Harper as a “tiny little thing … I guess you notice people who wanted to be noticed, and she wanted to be noticed. She was pretty in a plain way. Kind of coquettish. You couldn’t help but like her.”

Joan Tyre went to the same school as Harper but was two years older than the girl. In a 2005 police interview, Tyre recalled what Harper was like.

“Lynne used to come over to our house even though she was younger. We’d have parties in our basement and she’d want to come so sometime I’d invite her … but you know when you’re 14 and she’s 12—it’s kind of a big age difference … we were friends, but we didn’t hang out a lot together,” Tyre told police.

“She just wanted to belong. She wanted to do what the other kids did and not so much the little kids but more the older kids. She just wanted to have a friend … I don’t know if she got a lot of attention at home … I don’t think she got a lot of attention because she was very, I don’t know, clingy. She wanted to be with the bigger kids,” continued Tyre.

On June 9, 1959, Lynne Harper left the RCAF base with some other girls to play baseball.

“Lynne was on my team,” said Tyre. “She hit the ball and she didn’t run fast enough so she didn’t make it to first base. So, I gave her heck. I said Lynne, you run like an old lady and she goes ‘Well, I’m going home.’ She started to cry, and she left, and I thought, oh great, you know, here we are off base. I’m going to get in trouble for this.”

Harper apparently recovered her composure. She left the ball game and returned home. At 5:30 p.m., she ate a turkey dinner. Once dinner was done, Harper got into an argument with her parents. She wanted to go swimming at the pool on the RCAF base. Problem was, as a minor, she required adult supervision or a military pass to swim there. Harper went off to see if she could secure a pass from a base official but failed. She returned home in a huff, did the dishes then left the house again around 6:15 p.m. She did not tell her parents where she was headed.

In addition to her turquoise shorts, white blouse and brown shoes, Harper wore a locket around her neck with an RCAF crest on it. The locket had been a recent present from an aunt.

Harper walked up Victoria Boulevard and Winnipeg Road in the PMQs. Then she went north to a park area by A.V.M. Hugh Campbell School. She arrived at the school grounds at 6:30 p.m. A Brownie meeting was going on, and Harper eagerly joined in a scavenger hunt. Harper helped organize the little girls and chatted with an adult Brownie leader named Anne Nickerson.

“Lynn (sic) asked if she could stay, and about 6:40 p.m., I sat down under a tree and talked with Lynn (sic),” said Anne Nickerson in her police statement. “She said she didn’t want to go home; her mother was cross with her … I must have talked with her about 20 minutes. At about five after seven Lynn (sic) walked away and then a boy came along with red trousers and red shirt on. He had a bike and parked it and Lynne sat on the side. I didn’t know the boy, not by name, but by sight, and now believe it to have been Stephen Truscott (sic). They walked away together … him pushing the bike.”

This was not the first time Harper had approached Truscott. A few days earlier at a house party for local teens, the grade seven student had walked up to Truscott and asked him to dance. Truscott accepted and the two cut a few steps. All witnesses to the event stated that this was the full extent of their intimacy.

Now, at the school grounds, Harper had another request. According to Truscott, she wanted a ride down to Highway 8. She idly mentioned something about maybe seeing some ponies owned by a recluse who lived in a white house outside town. Several witnesses, including Nickerson, saw Harper and Truscott walk off together. When they reached the county road, Harper seated herself on Truscott’s handle bars and the two descen...