- 72 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This report explains how the quality of infrastructure investments in developing Asia can be enhanced and why this is vital for the region's sustainable recovery from the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. It emphasizes the need to balance urgent demand for infrastructure financing with governance approaches that focus on boosting efficiency and integrating infrastructure systems. The report also explores how the Asian Development Bank can strengthen its support for quality infrastructure in the region through its financing instruments, programs, and projects.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

SECTION 1

THE IMPACT OF COVID-19 ON ASIA AND THE PACIFIC

The coronavirus disease (COVID-19) has disrupted the construction, operation, and maintenance of infrastructure projects in countries around the world. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has labeled this economic downturn the “worst economic downturn since the Great Depression.”1 The IMF World Economic Outlook Update for 2020 characterized the pandemic as a “crisis like no other, an uncertain recovery.” The Asian Development Outlook (ADO) 2021 projects that combined gross domestic product (GDP) in the United States, euro area, and Japan will decrease by 4.8% in 2020 and expand by 5.3% in 2021.2

Central banks in advanced economies have taken policy measures to provide liquidity and restore investor confidence. In many Asian Development Bank (ADB) developing member countries (DMCs), central banks have relaxed monetary policy and provided fiscal support far exceeding those enacted during the 2008–2009 financial crisis. In addition, governments have mandated mitigation measures such as lockdowns and restrictions on travel to reduce COVID-19 infection and ease the stress on health systems. All these have curbed consumption and investment, disrupted production, and impacted global trade, supply chains, travel, and tourism.

The ADO 2021 reports that developing Asia will contract by 0.2% in 2021. Table 1 shows that growth will rebound to 7.3% in 2021, but GDP will continue below its pre-pandemic trend. The restrictions on economic activities needed to address the pandemic have triggered recessions across advanced, emerging, and developing economies. This has lowered investment, eroded human capital, and disrupted supply chains (footnote 2). ADB estimates that the Asia and Pacific region could suffer losses from $1.7 trillion to $2.5 trillion under different containment scenarios.3 In response, governments and international finance institutions have provided unprecedented funding of at least $10 trillion. ADB is helping DMCs respond to the immediate impacts of COVID-19 through an initial $20 billion response package (footnote 3).

Table 1: Asian Development Outlook April 2021 Gross Domestic Product Growth Rate

NIEs = newly industrialized economies.

a Includes Hong Kong, China; the People’s Republic of China; the Republic of Korea; Singapore; and Taipei,China.

Source: Asian Development Outlook database; ADB April 2021 estimates.

Throughout Asia and the Pacific, the economic slowdown has contributed to delays in infrastructure financed as traditional public sector projects and by public–private partnerships (PPPs). Airports, for example, provide a grim picture of revenues for 2020, with a 50% drop in total passenger traffic (to 4.6 billion) and nearly 57% in airport revenues (to $97.4 billion), compared to pre-COVID-19 forecasts. A 58.9% drop in revenues from pre-pandemic levels in the Asia and Pacific region in 2020 was forecast by the International Finance Corporation (IFC) in May 2020 (footnote 3).

In order to respond to the immediate challenge, governments will have to reallocate spending requirements and reduce spending. Although infrastructure investment has been useful in stimulating growth, the impact of COVID-19 will reduce capacity to fund infrastructure from government budgets due to lower revenues. While increased infrastructure spending will help stimulate economic recovery in some countries, other countries may not be able to provide enough fiscal support due to their debt and revenue positions leading to reduced infrastructure investment or prioritizing spending on more immediate needs.

Governments need to balance infrastructure investment with the need for debt and fiscal sustainability though the top priorities are public health and the need for continued fiscal support. Governments have launched a large fiscal response to address capacity in the health sector, provide income support to households, and avert mass bankruptcies. A rebound in growth in 2021 spurred by low interest rates should help stabilize debt-to-GDP ratios, but ensuring sustainable fiscal balances will be necessary for countries with elevated debt and low growth.

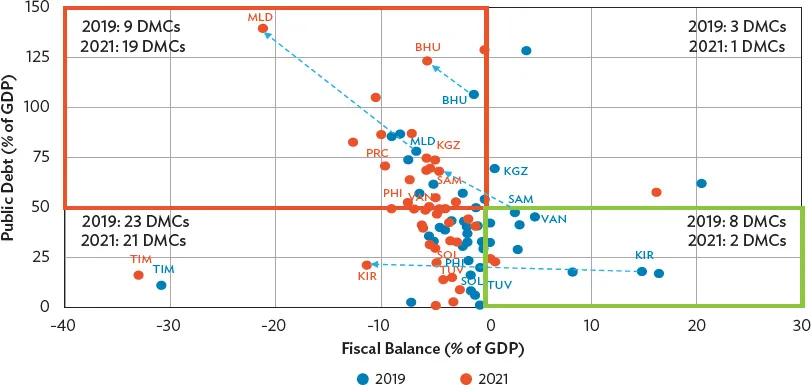

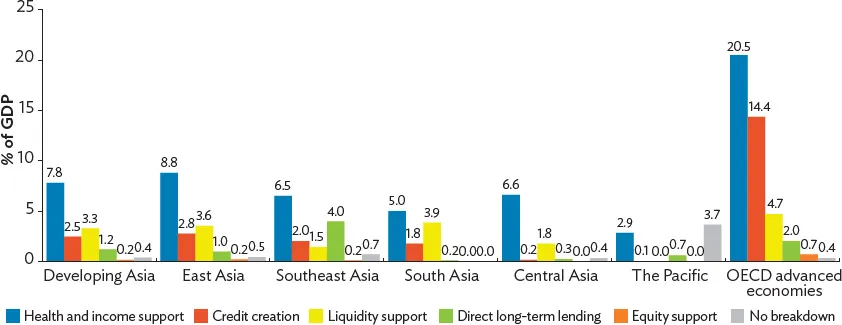

The ability of governments to fulfill infrastructure needs will be stressed, especially in low-income countries, given the collapse in economic activity and revenues and the expansion of other spending needs—most notably social support and health spending. Figures 1 and 2 show the increase in public deficits and debt because of the economic contraction and the increase in policy support, with governments spending about 8% of GDP on income support. There is much less room for public infrastructure spending, and countries need strong debt-management capacity. Indonesia, for instance, has issued (domestic or international) bonds, including a pandemic bond for $4.3 billion, to respond to the COVID-19 crisis and support economic recovery. Prior sound fiscal and debt management capacity has made this possible with a deficit under 3% and a debt-to-GDP ratio around 30%.4

COVID-19 has also decelerated progress in achieving the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). With scarce public resources channeled toward addressing the current public health crisis, DMCs have become even more constrained in delivering the infrastructure investment needed to achieve the SDGs. The pandemic affects the most vulnerable, especially in densely populated informal settlements and slums. However, progress in reducing slum populations has slowed in some regions.

Even before the onset of the pandemic, the Asia and the Pacific region was not well-positioned to achieve the SDGs by 2030. According to the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (UNESCAP), income inequality, measured by the Gini coefficient, increased by over 5% between 1990 and 2014.5 Close to 80% of the Asia and Pacific population live in countries with widening inequality (as measured by Gini coefficients).6 Despite significant progress on some goals, such as quality education (Goal 4), the region is likely to underperform on all the 17 goals by 2030. In particular, the region is sliding backwards and needs to reverse trends on climate action (Goal 13). Globally, current emission reduction commitments are insufficient and would lead to a 3.2°C rise in temperature this century—well above the Paris Agreement target of 1.5°C.7 The Asia and Pacific region emits half of the global greenhouse gas emissions, with the number doubling since 2000. The region’s share of renewable energy as a percentage of total final energy consumption has dropped from 23% in 2000 to 16% in 2016, one of the lowest rates among world regions. In 2018, natural hazards affected the livelihoods of 24 million people in Asia and the Pacific.8

Global poverty rates are rising for the first time since 1998 due to the pandemic. The April 2021 ADO shows that poverty would have continued its decline in developing Asia as in the past 2 decades.9 Poverty rates, defined as people living on a maximum of $1.90 per day, should have gone down to 104.1 million people by the end of 2020, but COVID-19 reversed this. The ADB report estimates the number of people living in poverty increased to 182.4 million by the end of 2020 using the $1.90 poverty line. Based on current GDP forecasts for a rebound in growth in 2021, the number of people living in extreme poverty in Developing Asia will decline to 132.5 million in 2021 and 104.4 million in 2022.

The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals Report 2000 estimates that South Asia will be one of the most affected regions with an additional 32 million people living below the international poverty line due to COVID-19.10 While these estimates may vary depending on the pace of recovery, they reveal the economic distress of the pandemic. Households in the affected sectors will suffer disproportionately. Poverty rates, for example, could double in Viet Nam for workers in manufacturing, dependent on imported inputs, and in some Pacific island countries where tourism is the largest employer.11 Women are more likely than men to work in sectors requiring face-to-face interaction, such as tourism, retail, and hospitality. These sectors are the most affected by social distancing and mitigation measures and suffer a disproportionate impact from shutdowns due to COVID-19.

Governments have turned to the task of restoring long-term and sustainable economic growth. The initial reaction to COVID-19 centered on meeting immediate needs, like supporting medical first responders and ensuring that hospitals had necessary medicines, supplies, and equipment. The economic stimulus that followed aimed to achieve economic recovery through such measures as cash transfers, subsidies, and increased spending to support specific sectors. In 2021, there are signs that the Asia and Pacific region is reversing the impact of COVID-19 and resuming positive rates of economic growth. The Asian Infrastructure and Investment Bank studied a sample of 24 engineering, procurement, and contracting (EPC) companies across the region.12

They found that despite devoting more resources to immediate COVID-19-related needs affecting project financing, completion, and future project development, the infrastructure sector nonetheless remained resilient in most Asian markets. EPC firms also showed signs of stock price recovery, strong revenues, and sound financials.13

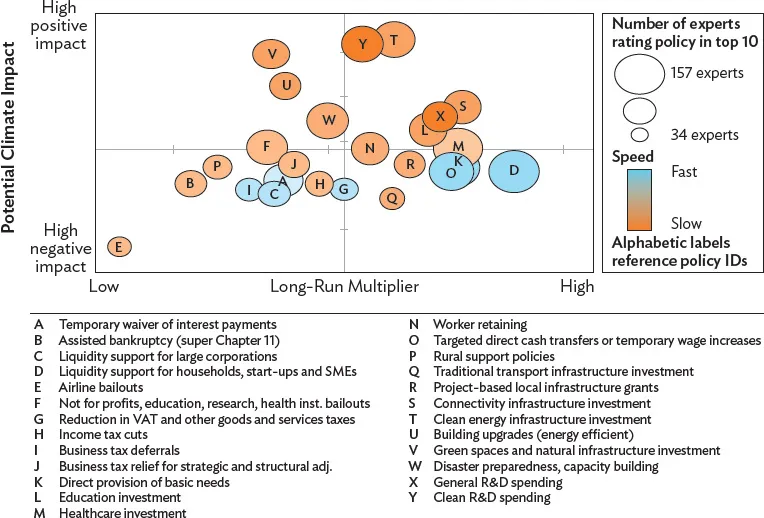

COVID-19 may give the region a prime opportunity to not only catch up on environmental targets, but also lay the foundation and build back better for a green, inclusive, and resilient transition. A recent survey on emergency fiscal response shows that strong support for green investments within stimulus packages will accelerate the speed of economic impact. The survey of 231 officials from central banks, finance ministries, and economic experts from G20 countries looked at the relative performance of 25 fiscal recovery policy models across four categories: economic multiplier, climate impact, speed of implementation, and overall desirability.

The survey identified five models demonstrating the most impact on the economic multiplier and climate impact: energy retrofits, clean physical infrastructure, education and training, natural capital investment, and clean energy research and development.14 Figure 3 shows which relief policy measures have the most impact on recovery according to the survey. Investments located in the center right of Figure 3 show good performance regarding implementation speed and the long-run multiplier. These policy measures include liquidity support for startups, small and medium households (D); support for basic needs (K); and direct cash transfers (O). Non-conditional airline bailouts did not appear in any of the experts’ top 10 policy measures.

The challenge after COVID-19 lies in having the resources to increase green investment and sustain it at higher levels, including adaptation and resilience against pressing fiscal and financing constraints. This requires effective domestic resource mobilization for infrastructure and basic services, as well as sustainable development finance and poverty alleviation. Building back better requires policies, institutions, and skills to build social resiliency, and resource mobilization and economic growth policies to support social and productive infrastructure and technology development. It will also require policy changes to ensure the correct market signals, supporting policies to sustain “green investments” such as subsidy reform/subsidy swaps ...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Tables, Figures, and Boxes

- Foreword

- Acknowledgments

- Abbreviations

- Executive Summary

- 1 The Impact of COVID-19 on Asia and the Pacific

- 2 Public Investment Efficiency in Infrastructure

- 3 Public Investment Management: Driver for Restoring Sustainable Economic Growth

- 4 Quality Infrastructure Investment: Knowledge Products, Tools, and the Infrastructure Governance Framework

- 5 Key Drivers of Quality Infrastructure: Efficiency, Accessibility, and Sustainability

- 6 Quality Infrastructure Investment: From Principles to Practice

- 7 Assessment and Performance of Quality Infrastructure Investment

- Footnotes

- Back Cover

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Supporting Quality Infrastructure in Developing Asia by in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Infrastructure. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.