- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

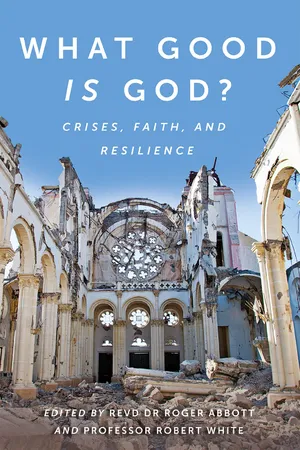

In a world where natural disasters are increasingly impacting our lives, this insightful book brings together a variety of voices to discuss how we can respond practically and faithfully to such tragedies.

Consciously making room for the perspectives of survivors, responders, and academics, it provides a multi-layered and compassionate examination of a difficult and often underexplored subject. As we try to make sense of a seemingly chaotic world that features earthquakes, tsunamis, and pandemics, readers will find this unique conversation a truly ispiring resource for thought, prayer, and action.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access What Good is God? by Roger Abbott,Robert White FRS in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Christian Theology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

DISASTERS: NATURAL OR UNNATURAL?

ROBERT WHITE

There is no such thing as a natural disaster.1

The world seems to be full of disasters, appearing on our TV screens and newspapers on a weekly basis. Some are clearly caused by humans: bridges fall down; buildings catch fire and incinerate many people; dams collapse and drown folk; terrorism and war inflict terrible suffering and atrocities. Others seem to be arbitrary, just “acts of God”: earthquakes; volcanic eruptions; floods; outbreaks of highly infectious diseases. They are things that we feel should not happen in a well-ordered world. Yet they persist.

From a Christian perspective, the problem is especially pointed. Christians believe in an all-powerful, sovereign God, who is perfectly just and completely loving: so why does he permit disasters to happen? Indeed, all the monotheistic religions face the same knotty problem. Arguably, those with no faith commitment ought not to be so troubled, since there is then no reason why the world should be a just or a moral place; yet of course the pain, the suffering, and the tragedies are just as bad for everyone.

The problem has been debated and written about for millennia, so I do not claim to give any pat answers here. But nevertheless, there are some things we can say about the reasons for disasters. I will also review briefly what the writers of the Bible had to say about disasters: and they certainly knew all about them, because people in the Middle East where the biblical narrative unfolds have always experienced disasters, including famines, floods, earthquakes, and volcanic eruptions, on top of conflict and warfare.

In short, the message of this chapter is that what we call “natural” disasters − the floods, volcanic eruptions, and earthquakes − are the processes that make this world a fertile, habitable place where humans can thrive. These generally beneficial natural processes are frequently turned into disasters, primarily by the actions, or inactions, of humans. Thus, we might term them “unnatural disasters” rather than “natural disasters”.

In the case of earthquakes, this is captured well by the aphorism “first the earthquake, then the disaster”.2 It has been applied many times, possibly starting with a 1970 earthquake in Peru which killed over 70,000 people. The disaster in Peru to which locals referred was the way in which subsequent heavily funded reconstruction and development programmes were directed from outside the affected communities by remote and aloof managers, with minimal regard for local leadership, organization, or community participation. In effect, they destroyed what had formerly been vibrant, self-driven, and motivated local networks and communities. We found exactly the same phenomenon in Haiti after the devastating 2010 earthquake that killed around 230,000 people: external aid agencies which flooded into the country often ignored local expertise and knowledge, then in a relatively short time left the country, leaving the communities worse off than before (for more, see my co-authored title with Roger Abbott, Narratives of Faith from the Haiti Earthquake).

The good Earth

On Christmas Eve 1968, the three crew members of the Apollo 8 spacecraft – Frank Borman, Bill Anders, and Jim Lovell – broadcast a last message before they traversed behind the Moon for the tricky manoeuvre of firing the retro-rockets manually to get them out of Moon orbit and on the way home. Anders began: “For all the people back on Earth the crew of Apollo 8 has a message we would like to send you”. Then they read through the first ten verses of the book of Genesis, each in turn. Borman ended the broadcast: “From the crew of Apollo 8, we close with good night, good luck, a merry Christmas, and God bless all of you − all of you on the good Earth”.

At the time, it was the biggest broadcast ever, estimated to have attracted an audience of about a billion people – one quarter of the global population. The iconic photograph taken on that same flight showing the earthrise of a richly coloured planet above a barren moonscape has become the most widely reproduced image in the world. It has been credited with kick-starting environmental concerns.

The sentiment the astronauts expressed of the inherent goodness of the Earth mirrors exactly the biblical view of creation. Six times in the first chapter of the Bible, after each creative day, God is reported as seeing all that he had made as “good”. Then after he had made humans, “God saw all that he had made, and it was very good” (Genesis 1:31, NIV). There is not much mistaking the message of the goodness of creation.

There is, however, a catch. In the light of the disasters we experience around us, the world does not always feel as if it is good: it feels broken, somehow out of kilter. And the blame for that lies with humankind’s rejection of God: what is often termed the “fall”. The “goodness” of creation as described in Genesis is sometimes explained as a fitness for purpose. The created order fulfils, or begins to fulfil, God’s intentions. Genesis and other biblical passages that describe the origins of creation provide the indispensable basis for any Christian discussion of how we relate to the rest of creation (for more, see my co-authored title with Jonathan A. Moo, Hope in an Age of Despair).

What about those natural processes that often create disasters: floods, volcanic eruptions, and earthquakes?

The most common disaster, which kills by far the most people, is flooding. Yet floods are a crucial means of distributing fertile soils eroded off mountains and deposited in river valleys, then used for agriculture. For millennia, it was the annual flood of the Nile that enabled Egypt to prosper. When the Nile flood failed, as for example in 1784, one-sixth of the population died.3 A French traveller reported that “the Nile again did not rise to the favourable height, and the dearth immediately became excessive. Soon after the end of November, the famine carried off, at Cairo, nearly as many as the plague”.4

Another natural hazard, volcanic eruptions, are crucial to the fertility of the Earth. They continually cycle to the surface from deep inside the Earth huge volumes of minerals essential for life. Volcanic islands such as Hawaii support lush growth of plants and animals, and are some of the most biodiverse areas on Earth. Volcanoes also provide the geological source of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. Without that, the planet would probably have been frozen for most of its history. The average surface temperature in the absence of greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide in the atmosphere would be about –6°C or lower.5 This would have prevented the existence of most and maybe all of life, including humans. Yet volcanic eruptions may be explosively fatal to humans caught up in them.

Considering earthquakes as the last of this trilogy, they occur with a suddenness that is frequently catastrophic if they are near major cities. Yet without earthquakes there would be no plate tectonics and no mountain ranges. The continual building and erosion of mountains and the eruption of molten rock as part of the plate tectonic cycle provides a steady supply of nutrients which allows life to thrive. Another example of the role of mountains produced by the action of plate tectonics is that without the Himalayan mountain range the annual monsoons which provide water for 1 billion people in India would not occur. Mountain ranges, which grow through frequent earthquakes as the Earth’s crust deforms, cause rainfall which in turn makes the land fruitful and habitable. These examples can be multiplied many times.

Although natural processes are beneficial in generating a suitable home for humanity, it is when humans interact poorly with them that a natural process can turn into a disaster.

Disasters

A major factor, which makes disasters more devastating today than in the past, in terms of the numbers of people killed or affected, is the exponential increase in global population: there are almost five times as many people alive today as there were a century ago. Add to this the fact that more people now live in cities than in dispersed rural areas and that those cities are usually in river valleys or by the coast, and it is inevitable that large numbers of densely packed people are far more vulnerable to natural hazards than in the past.

Another critical factor is poverty: high-income nations and rich people can generally buy themselves out of trouble, either by building safe homes before a flood or earthquake, or by rebuilding afterwards. Poverty makes that much more difficult, though not impossible. In terms of losses, the lowest-income countries bear the greatest relative costs of disasters. Human fatalities and asset losses relative to gross domestic product are higher in the countries with the least capacity to prepare, finance, and respond to disasters.

Set against that vulnerability caused by population increase is an equally rapid increase in scientific understanding of how the natural world works. In principle, this means that natural hazards can be recognized and understood better, and as a result appropriate mitigation or adaptation strategies put in place. Key to this is education. Even the seemingly minor fact that 10-year-old Tilley Smith had heard about tsunamis from her geography teacher meant that she recognized the devastating Indian Ocean tsunami on Boxing Day 2004 as it approached the beach they were on. She was able to persuade her family and then others on the beach to move off it, saving maybe 100 lives.6 The passing on of folk knowledge from previous generations who have faced similar hazards also has huge value.7 Although the same tsunami killed over 230,000, people living on Simeulue island off the Sumatran coast, and the Moken people living in the Surin Islands off the coast of Thailand and Myanmar used knowledge passed on orally from their elders to survive it, despite being so close to the most affected areas. They knew that when the sea retreated suddenly, especially when it followed a period of earthquake shaking, then they should run immediately to high land. That knowledge saved their lives.

Earthquakes

Earthquakes cannot be predicted, but areas at risk are becoming understood better. Buildings and infrastructure can be built to be resilient against earthquakes, and to protect people. One of the triumphs of the 2011 Tohoku earthquake in Japan is that despite the magnitude 9.1 earthquake being 30 times larger than the maximum expected in this region, no one in Tokyo was killed by the earthquake because buildings did not fall down. And early warning systems that automatically detected the earthquake 12−15 seconds before the damaging surface seismic waves arrived applied emergency brakes that stopped 33 bullet trains travelling at average speeds of 300 km/hr. This saved many lives. Some 23,000 people unfortunately died from tsunami flooding: this wasn’t due to a lack of awareness of the dangers of tsunami, but rather because it was even larger than expected or planned for. Ironically, some people lost their lives, despite there being adequate warnings, because they trusted too much in their tsunami protection walls, so did not try to escape to higher ground: indeed, some actually went down to the tsunami walls to watch the spectacle, with fatal consequences.

More shockingly, the likelihood of dying in an earthquake depends primarily on your poverty level or that of your country. A stark example is that the magnitude 7.0 earthquake in the low-income country of Haiti in January 2010 killed around 230,000, despite having 1,000 times less energy than the 2011 Tohoku earthquake. The deaths were caused primarily by poorly built buildings collapsing on top of people. It isn’t that we don’t know how to build earthquake-resistant buildings, as was demonstrated graphically by the fact that a 13-storey plate-glass-windowed skyscraper owned by the Digicel telecommunications company in Port-au-Prince survived without a single window being broken, while the newly built adjacent four-storey Turgeau hospital collapsed on top of many patients and medical workers (see Figure 1.1).

Volcanoes

In general, volcanoes give warning signs before eruption which often allow people to evacuate safely. However, those warnings are sometimes purposely ignored, in which case there is no doubt that there is human culpability in the resultant deaths and injuries. A notorious example was the Mount St Helens eruption in 1980. Throughout March, seismic activity increased, with a small summit eruption on 27 March. By 30 April, local authorities had defined an exclusion zone extending 2–18 miles (3−30 km) from the volcano. But 83-year-old Harry Truman, who had lived at Spirit Lake for decades with his 16 cats, refused to leave. He was killed and buried under 150 ft (45 m) of ash when a cataclysmic eruption occurred on the morning of Sunday 18 May.

In Harry Truman’s case, it was his own decision to stay, despite the efforts of the law enforcement officers to persuade him to leave. But a worse example, and the biggest volcanic disaster of the twentieth century, occurred on 8 May 1902. An estimated 26,000-36,000 people died when Mount Pelée in Martinique erupted violently at eight o’clock in the morning (according to Thomas and Morgan-Witts’ The Day Their World Ended). All but one person died in Saint-Pierre, the largest city of Martinique, which was only 4 miles (6 km) from the foot of the volcano (see Figure 1.2). Yet there had been ample warning: the volcano had been spewing out ash and mud flows, with numerous earthquakes, for over two weeks. The city was chaotic, with water and food supplies failing, civil unrest, an outbreak of fever, and an influx of people from surrounding rural areas. Yet the governor actively prevented people leaving, even stationing soldiers to stop them walking the 11-mile (18 km) trail to the safety of the nearby commercial capital of Fort-de-France.

Why was the governor so keen to prevent people evacuating Saint-Pierre, against all common sense? The reason was that elections were due on 11 May, and the new socialist party which spoke primarily for the island’s black and mixed-race majority looked set to wrest power from the conservative elite of white and French expatriates. A large majority of the conservative voters lived in Saint-Pierre. The minister of colonies in France may have ordered the governor to keep Saint-Pierre’s voters in town until the election was over (according to Solange Contour’s Saint-Pierre, Martinique, Vol. 2, La Catastrophe et ses suites, 1989). In partial mitigation of the governor’s actions, the ferocity and speed of the burning pyroclastic flows which overwhelmed Saint-Pierre was not well understood prior to the eruption. In fact, the volcano, Mount Pelée, thereafter gave its name to such volcanic flows: Peléan eruptions. In any case, it was an avoidable tragedy because the authorities first discouraged, then prevented, people leaving.

Floods

Floods affect more people than all other natural disasters combined. On 12 November 1970, half a million people died in a single night from a flood in East Pakistan when the Bhola cyclone hit the coast. Numerous other examples occur every week, right down to the deaths of one or a few people when rivers burst their banks.

Floods disproportionately affect low-income countries and poor people, because high-income countries can protect themselves more effectively. Following tidal surges in 1953 which inundated large areas of eastern En...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Chapter 1. Disasters: Natural or Unnatural?

- Chapter 2. Disasters, Injustice, and the Goodness of Creation

- Chapter 3. “What Good is God?” Disasters, Faith, and Resilience

- Chapter 4. Physician Heal Thyself: His Grace is Sufficient

- Chapter 5. Disasters, Blame, and Forgiveness (with Special Reference to the “Lockerbie Disaster”)

- Chapter 6. Haitian Womanhood, Faith, and Earthquakes

- Chapter 7. Disaster: What Survivors Think, and How Best to Help

- Chapter 8. How One Church Survived Hurricane Katrina (and What They Learned, with the Help of God)

- Chapter 9. Climate Change: A Disaster in Progress

- Chapter 10. COVID-19 Pandemic: A Christian Perspective

- Afterword

- Author Profiles

- Picture Acknowledgments