- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

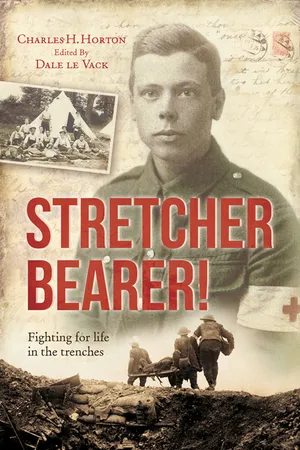

About this book

Among the thousands of men who shivered and suffered in the trenches during the First World War, some did not even have the protection of a weapon. Members of the Royal Army Medical Corps (the RAMC) were there not to take lives, but to save them. Many chose this difficult and dangerous work because of their principles - including volunteer Charles Horton, who went through the horrors of Passchendaele, Ypres and the Somme, fighting to get the injured away from the guns, to the safety of the field hospitals and beyond. After the war, Horton felt that the RAMC and their sacrifices were forgotten, and so in 1970 he wrote down his memories. In this glorious book, full of first hand detail, he takes us back to the trenches in France and the mountains of Italy. This is a wonderful authentic account into one man's struggle to survive - and to keep others alive. With the approval of Horton's family, author Dale le Vack has edited Horton's journals for clarity, and added more text to provide background. The result is a superb memoir of one of the darkest periods in history.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Stretcher Bearer! by Charles Horton, Dale le Vack in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Historical Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

INTRODUCING CHARLES HERBERT “BERT” HORTON

This is a book about a non-combatant in the front line in the First World War who was there not to kill men but to save them. It has been published, long after the death of its author, as a testimony to ordinary men like him who were in the armed forces during the First World War. He set out to explain in his memoirs what it was like to be an ordinary bloke serving as a stretcher bearer in the army during the conflict.

When he wrote about his war, Private Charles Herbert Horton (2305), who served on the Western Front and in Italy, wanted to record for posterity the everyday life of men who volunteered for service and endured the dangerous but often tedious army life on active service, usually without recognition – apart perhaps from a service medal or two. Private Horton was entitled to wear the Victory Medal and the British War Medal but there is no record that he ever bothered to apply for them.

These memoirs are historically valuable because they are among the few personal accounts published about men from the ranks. He writes:

There is an almost complete absence of any personal history of the many thousands who exchanged civvies for khaki to serve in the ranks, to do as authority told them and to accept the ordeal of deadly danger, rough conditions and some ineffable boredom for month after month and year after year, and who were still lucky enough to survive to the end.

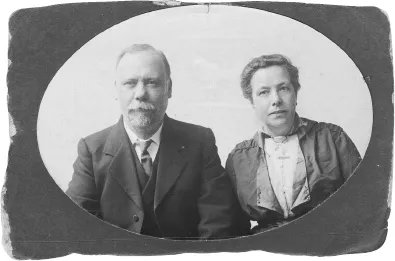

Charles’s father and mother, Joseph and Harriet Horton

Charles Herbert Horton, known to his family as Bert, was a 19-year-old graduate when he joined the RAMC. He came from a deeply Christian middle-class family living in Handsworth, Birmingham, and he attended Handsworth Grammar School, where he was a scholar. His name is to be seen in the school register in the entrance hall. At the outbreak of the war he was about to enter his third year of studies for a degree in commerce at Birmingham University.

Joseph and Harriet Horton brought up their three children, Nellie, Bert, and Joseph Arthur to have Nonconformist religious beliefs.1 Joseph was a preacher on a Methodist circuit2 for much of his life and was associated for thirty years with Asbury Memorial Wesleyan Church, Handsworth, in which he was leader of the Young Men’s Bible Class. In fact he held every office open to a layman. A keen musician, Joseph was a flautist and a member of the Birmingham Choral and Orchestral Society. Bert’s brother, Arthur, became organist at Perry Barr Wesleyan Church.

Bert, an accomplished violinist, inherited from Joseph a strong personal distaste for conventional soldiering, because it would involve him in killing men. He was patriotic, however, and so, after getting his degree in 1915, he opted to volunteer to join the corps in the British Army that was dedicated to saving life rather than taking it – and he did so as a stretcher bearer prepared to serve overseas in front-line duty.

He was also prepared to set aside the possibility of obtaining a commission to which his education had prepared him, because in the Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC) these were reserved exclusively for doctors, dentists, and other professional specialists in the field of medicine. In any case, being an officer in the RAMC would have meant carrying firearms and learning to use other weaponry, a requirement for all who held the king’s commission.

Instead, Bert served in the ranks of the corps and despite his education and intellect was content to remain a private soldier throughout his years in the army, even turning down the opportunity to become a non-commissioned officer. He seemed to want no part of the military command structure, preferring to remain in and around the front line – dedicated to saving life.

His intellect and bilingual skills were finally recognized at the end of the war when he was selected to be a member of a British Army delegation from the RAMC to travel to Vienna, whose mission was the safe return of British prisoners of war.

He came from a generation taught not to express emotion or pass on to others the full horror and butchery of warfare in the trenches, for example, in his letters home. Censorship also ensured he could not do so in these letters. It was expected of young men from a Nonconformist background that they should be modest in both thought and expression. This was the kind of man that Bert Horton was. It comes through clearly in his writing. He told his family that unless illness prevented it, he never missed chapel on a Sunday, even while he served on or near the front line.

In this book the vivid horrors of war are left largely for others to imagine. There are no passages that describe in shocking or dramatic detail what he witnessed in the battlefield. He never tells us of the distress, pity, or revulsion he must have felt at the sights, sounds, and smell of the dead and the soon to die.

Bert Horton knew that death stalked him and his comrades: the fear of it, the horrific sight of shattered bodies, the screams of the dying and the constant shelling. However, we never hear about the physical ordeal of carrying a human being across bog-ridden terrain, the mud, the biting cold and endless drizzle, the disgusting nature of dressing wounds that may have turned septic or been spewing puss. Yet he was familiar with them all in the heat of battle in the advanced dressing stations to which he brought the wounded.

He seems to have preferred that his personal account of the war should sound ordinary, even humdrum. Of course, it was not, but we can only speculate the underlying reason for understatement. It may be that the mental effort required in recalling in detail the horrors he witnessed in the written word was just too painful for an old man. Perhaps he could not bear to relive them. One of the stated reasons for Bert Horton writing his memoirs is protest.

In the aftermath of battle, the RAMC stretcher bearers – as opposed to regimental stretcher bearers – rarely received official recognition for what they had done in the shelling zone where they were usually based. None of the RAMC men awarded the Victoria Cross were stretcher bearers from the ranks. They were all officer doctors.

Several VCs, however, were awarded to regimental stretcher bearers who accompanied combatants into action. These men were ordinary soldiers who had volunteered to augment and work alongside regimental bandsmen, who traditionally did the job on the battlefield. Unlike RAMC stretcher bearers they were also trained to carry and use firearms.

Regimental stretcher bearers were more likely to win medals for conspicuous gallantry than RAMC stretcher bearers, not necessarily because they were more courageous, but because they worked primarily from the regimental aid posts and were right on the front line – and were required to venture into no-man’s-land alongside the fighting men.

By contrast, for much of the time (there were many exceptions), the RAMC stretcher bearers were positioned behind the immediate area of no-man’s-land, taking the wounded to the advanced aid posts. In this area, just to the rear of each of the opposing armies, stretcher bearers were often exposed to continuous shell-fire, but less often to bullets and bombs thrown at close range.

Many RAMC stretcher bearers, including Bert Horton, believed that their war service went largely unrecognized because they did not (and in some cases were not prepared to) bear arms against the enemy. However, no official documents have ever come to light that would confirm this suspicion.

Significantly, after 1916 the RAMC was the chosen corps of thousands of men who refused to fight under any circumstances – the registered conscientious objectors or “conchies” as they were known.

The popular belief that “conchies” were at heart cowards was exacerbated because the post-1916 conscientious objectors were not volunteers – as Horton was – but conscripted men who were required by law to fight for king and country. Many “absolutists” – as some conscientious objectors were known – were imprisoned for refusing even to wear the army uniform and to participate in any form in the war effort. They were marked men, deemed unemployable, for many years after the war when they returned to civilian life.

There were exceptions when a gallantry medal was awarded to an RAMC stretcher bearer who was registered as a conscientious objector. Private Ernest Gregory was a conscientious objector who refused to fight, but he was also a volunteer in the corps, like Bert Horton had been. Gregory “the conchie” – as he was called – won the Military Medal in 1917 during the Battle of Passchendaele. The citation reads:

Pte Gregory of the 1/3rd West Riding Field Ambulance RAMC was awarded his medal for conspicuous bravery in the field for bringing in wounded men in terrible conditions – under fire and through shell holes and mud-filled water up to the armpits.

Although Bert Horton does not reveal in detail the acts of heroism he himself and other private soldiers performed, or actually witnessed, during the summer of 1916 and later in 1917, it is clear that acts of conspicuous bravery, often carried out on the spur of the moment, were taking place all around him – both during the Battle of the Somme and in the Third Battle of Ypres at Passchendaele.

Books and films about the Great War have shown that acts of spontaneous bravery by unsung heroes that might have resulted in gallantry awards took place every day, but were not recognized or recalled in the aftermath of combat, sometimes because no one was left alive to validate them.

At the same time, it would be incorrect to claim that stretcher bearers serving in the RAMC were never recognized for their gallantry in the field – because 3,002 non-commissioned officers and other ranks in the corps received the Military Medal between 1914 and 1918, some with bars. However, the award of the Distinguished Conduct Medal, the Military Medal, and other gallantry awards to other ranks in the RAMC constitutes well under 2 per cent of the 120,000 men and women who served in the corps during 1914–18.

Bravery awards in the First World War were the result of an administrative route which began with the act of conspicuous bravery itself. The system started with someone considered of responsibility witnessing an act and reporting it into the chain of command. At each reported stage, consideration was given to taking it a stage further. Assuming that the full consideration path was followed, the stage was reached where someone in the command structure had the job of confirming the award or denying it.

In old age in the 1970s Horton, who as we know was not a registered conscientious objector, argues that the RAMC is possibly the most overlooked of all branches of the services – rarely referenced by war writers or war records. Humble and modest men like Private Bert Horton of the RAMC remained in the shadows of military existence.

One can detect in Horton’s writing over half a century later a sense of frustration that public interest in the Great War appeared to have diminished significantly as he became an old man. Bert Horton did not live long enough to witness the revival in the public appetite for publications, both factual and fictionalized, about the First World War.

The outbreak of the First World War in August 1914 is now perceived correctly as the setting from which many of the traumatic events of a troubled century sprang during successive decades. The question remains whether the young generation of the early twenty-first century will learn from it. Bert Horton tells us:

Not all the war memorials and Armistice Day Festivals can pay a tithe to the tribute due to those whose lot it was to be offered up as cannon fodder in this most bloody of all campaigns the world has seen.

2

I970: REFLECTIONS ON A CONFLICT

EXTRACTS FROM BERT HORTON’S DIARIES

Over several decades in the twentieth century, a generation grew up who knew little of the anniversaries of the historic episodes of the Great War, such as on 1 July 1916, the first day of the Battle of the Somme. We surviving combatants who served in the trenches in the Great War, now old men, usually felt a sense of reluctance to speak or write about any of the events connected with it, except perhaps the beginning and the end.

Whether the opening day of the Battle of the Somme is one of those events which the student of history, long after my generation has faded away, will ultimately be required to remember, is perhaps debatable.

Nevertheless, it is certain that for the dwindling numbers of us left, the date 1 July 1916 and the four and a half months that followed it, will continue to recall ineffaceable personal memories – as full of emotion as any other date on the calendar, even Armistice Day.

To hundreds of thousands of veterans in all parts of the earth it must always be a day of mourning – for probably on no other single day were so many brave men sent to eternity. They were our band of brothers, whose young lives were cut short.

“Between the rising and setting of one summer sun” as the late Conan Doyle put it, more than 100,000 British, French, Commonwealth, and German combatants became casualties. To those of us who took part in the battle and survived it, the memories of our individual experiences return as vividly after the passage of the years as they ever did. For all this horror the memories have something of grandeur in them which makes us a little sorry, maybe, for those of later generations who may have nothing so vivid to remember.

It is not my intention to recall once more the heroism of the men who went over the top in the great bid for victory, nor do I wish to portray the horrors which my job of Royal Army Medical Corps stretcher bearer gave me a special opportunity to witness. To paint either aspect of the picture more adequately than it has been done before is beyond my powers. The published accounts, which exist from the pens of eyewitnesses and others, make salutary reading. In the following pages, I have set down most of what I remember of the experiences of myself and my ambulance unit in the two and a half remaining years of the war and the months of waiting for release from service.

I want to answer the question why I have troubled, after the lapse of half a century, to set down this record. I think that the urge came upon me in retirement and ripe old age, partly because of the conviction that history is the sum total of the experiences of individuals.

As we learnt it, history is the story of the exalted ones and their ambitions and their rivalries, of governments and kings, of international diplomacy, of the strategy of wars, the causes of victory and defeat. The wars were fought by professional soldiers. The two great wars of the twentieth century were waged mainly by civilians-turned-soldiers.

The Second World War, involving as it did for the first time in this country th...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Introduction: The Royal Army Medical Corps

- 1 Introducing Charles Herbert “Bert” Horton

- 2 1970: Reflections on a Conflict

- 3 Europe Violated

- 4 Arrival in France

- 5 Eve of the Battle

- 6 First Day of the Somme

- 7 Battle of the Somme

- 8 Third Battle of Ypres (Passchendaele)

- 9 Italian Front and Armistice

- 10 Mission to Vienna

- 11 Demobilization

- 12 Bert in Civilian Life

- Appendices

- Notes