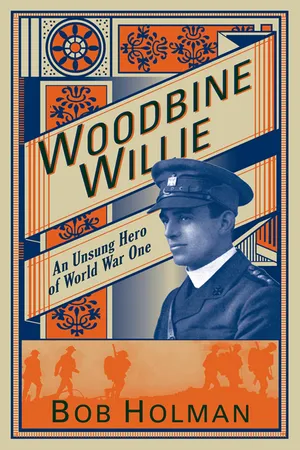

The writer of these words did get through the shells and bullets. The wounded got the morphine, and the writer was awarded the Military Cross. His name was Geoffrey Studdert Kennedy, although he was nicknamed “Woodbine Willie” because of his habit of doling out cigarettes to the troops.

These troops who lived in the trenches and survived the First World War did not just remember the fighting. Some could always smell the stink of buckets used as toilets. Others always shuddered at the thought of thousands of rats who chewed anything, including dead bodies, and licked the sweat off the faces of sleeping men. For some it was the freezing cold which, on guard duty, was so intense that they lost movement in their legs. For Studdert Kennedy it was the screams of wounded soldiers, particularly as he dragged them from the front line to the hospital.

Geoffrey Studdert Kennedy was a Church of England priest who in 1916, at the age of thirty-three, had volunteered to be a chaplain. Very quickly he was on the front line, helping doctors treat the injured, trying to staunch the blood, holding them during operations, and offering words of hope. Frequently he advanced with the men when they went over the top towards enemy fire. He would drag back the badly wounded, pray over the dying, and bury the dead. He was sometimes described as ugly. He might have lacked good looks but he never lacked courage.

His Childhood

Geoffrey Anketell Studdert Kennedy was born in a vicarage in Leeds on 27 June 1883. He was thus a Victorian, part of a Britain noted for its industrial wealth and worldwide empire. But there was another side of Britain – people in poverty. At this time, studies of poverty were few. One of the first was Seebohm Rowntree’s survey of York, for which he interviewed a large sample of people and took precise measurements of their incomes and expenditures.2 In 2007, Gazeley and Newell used newly discovered material from 1904 which had been based on the Rowntree approach. They revealed that in northern towns such as Leeds, some 16.8 per cent of the wage-earning class was in primary poverty; that is, their income was not sufficient to meet “the necessities of life”. For a couple with three children this meant their weekly income was below 21s. 8d. a week.3 The area of Quarry Hill, where Studdert Kennedy was born, was characterized by back-to-back housing with the grim workhouse, the Cemetery Tavern, and the parish church of St Mary’s in the midst.

Geoffrey Studdert Kennedy’s father, the Reverend William Studdert Kennedy, was the vicar of St Mary’s. Born in 1826, he was an Irishman and the son of a clergyman. He served at churches in Ballymena and Dublin before moving to a church in Forton, Lancashire, and then to St Mary’s. With his first wife, a Miss Russell from Malahide in Ireland, he had five children, named Mabel, Norah, Eve, Frances, and John Russell. After the death of this wife, the Reverend William married nineteen-year-old Joan Anketell, also from Ireland, by whom he had a further nine children who were, according to age, Rachel, Kathleen, William, Robert, Hugh, Maurice, Geoffrey, Cecil, and Gerald. The family was large even by Victorian standards and included William’s mother for a while.

Of the seven boys, four were ordained into the ministry. Most of Geoffrey’s siblings were academically able, with two taking degrees at Trinity College, Dublin, and they no doubt stimulated his own educational progress. He kept in touch with his siblings as they all grew up, and some of them left affectionate records of him and his childhood, including his brother William. Commenting on Geoffrey’s early years, William wrote:

In turn, Maurice wrote:

He added, “There were lots of good natured family jokes at his expense – particularly in regard to his capacity for becoming entirely lost and absorbed in every sort of book.”6

His sister, Rachel, commented:

These loving commendations all came from siblings but Geoffrey does come over as a loving and kindly young man.

Joan Studdert Kennedy was an exceptional woman. The census records show that some of the children from the first marriage still lived with the family at various times. John Russell was there for a while and, in 1901, so were Mabel, Norah, and Eve, although they were all over thirty and may well have made practical and financial contributions to the home. The census of 1881 also shows a cook in residence and the census of 1901 mentions a nurse. But it was Joan who oversaw the running of the home and ensured that harmony was maintained. She also cared for her husband, managed the large vicarage, helped in parish work, and participated in a secular choir in Leeds – perhaps that was her relaxation. Clearly she was a woman who was devoted to her family, and Geoffrey later displayed a similar characteristic.

Remembering his mother in later years, Geoffrey wrote:

Little is recorded of how his father related individually to Geoffrey. He led a busy life with so many children and a large parish, so his time must have been limited. But it is clear that he participated joyfully in family gatherings, debates, and celebrations. Geoffrey’s best friend from secondary school, J. K. Mozley, who later became an Anglican minister and well-known writer, spent much of his time at the Studdert Kennedy home. He recalled that he never had to knock on the door but just walked in and always received a warm welcome from the family and then enjoyed “the deep harmony which prevailed among them”.9 Brother Gerald especially treasured Christmas at the home and wrote:

The Church of England has had many unknown clergy who devoted their lives to serving their parishioners. The Reverend William Studdert Kennedy was one such, a priest who would now be almost forgotten had he not been the father of Geoffrey. His church was a very large building which was rarely filled to capacity. He worked hard and diligently, never seeking and never gaining distinction. Years later, Geoffrey observed that his father did not win many to Christianity but those he did tended to stay faithful for life.

J. K. Mozley noticed from his stays at the vicarage that “The district was very poor… When I first knew it, before large measures of slum clearance was carried out, it was, especially near the church, a region of poor and ill-lighted streets and alleys.”11 The Reverend William Studdert Kennedy did not neglect his parishioners, and Mozley also noted that he had a core of loyal, working-class worshippers. This must have affected Geoffrey. Michael Grundy, in his book on Geoffrey, commented that during the days at St Mary’s:

It is important to note that his concern for the working class did not start when he was a chaplain. From childhood onwards, it was as though he was being prepared for it.

Geoffrey started his formal schooling at the age of nine, when he joined a small private school run by a Mr Knightly. At some point, probably with the aid of coaching from Knightly, he also studied for Trinity College, Dublin, where it was possible to take its exams without being a regular resident. It is of interest that by 2012 the college did list him as one of its well-known students.

At the age of fourteen, he transferred to Leeds Grammar School under the headship of the Reverend John Henry Dudley Matthews. The school was over three centuries old and was local, independent, and for day pupils. The number of boys had declined in the 1880s and Matthews was appointed in 1884. Educated at Rugby and Oxford University, he was only forty but already had experience as a headmaster. He improved the libraries, the conditions of the buildings, the teaching of languages, and put an emphasis on science. By 1896, the roll showed 161 pupils. Fees were modest and thirty-five scholarships were available, and it is possible that Geoffrey obtained one of these.

He soon settled as a bright student ready to participate in all the school’s activities. A school contemporary, Alfred Thompson, commented that Geoffrey was “a very valuable member of the school, a fellow with a really good brain, a hardworking and intelligent Rugger forward with plenty of strength and grit, and a good long distance runner. He was by no means a bad gymnast, being very evenly balanced in bodily development.”13 In the 1901 school sports competition he won the quarter mile race.

Nor was he just interested in sport: he was also a leading member of the school’s Literary and Debating Society, and during his last debate there, according to Mozley, he seconded the opposition to the motion “That England has mainly herself to thank for her unpopularity abroad”. Mozley then quotes from the school magazine, which said that “he made an excellent speech, which again took the debate out of the domain of hard fact to the region of abstract ideas”. Commenting on his school career overall, Mozley added: