eBook - ePub

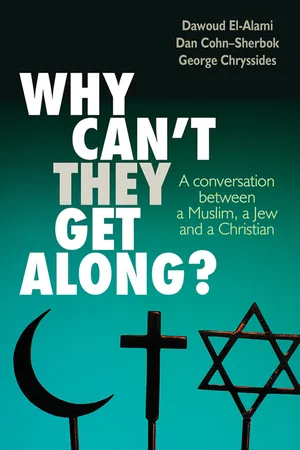

Why can't they get along?

A conversation between a Muslim, a Jew and a Christian

- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Why can't they get along?

A conversation between a Muslim, a Jew and a Christian

About this book

Christians, Muslims and Jews all stem from one man, Abraham, and yet relations between them are so often strained. Three men of faith: one Jew, one Muslim and one Christian debate the differences between them. The result is a compelling discussion: What do their faiths teach on the big issues of life? What can be done to make for better relationships in the future? What can be done on the big global areas of conflict and tension? How can they get along? For hundreds of years, many of the biggest global conflicts have been fuelled by religious hatred and prejudice. It is evident, in the early part of the 21st century that not much has changed. Whether it is fundamentalist Muslims waging jihad in Afghanistan and Pakistan, or the perpetual low scale hostilities between Israel and the Palestinians, to the man in the street, religion seems to make people more likely to fight each other, not less. Why is this? Why Can't They Get Along? is a powerful and much needed account. Current, passionate and compelling it is essential reading.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Why can't they get along? by Dan Cohn-Sherbok,Dawoud El-Alami,George D Chryssides in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Comparative Religion. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

TEACHINGS

CHAPTER 1

PREDICAMENT AND HOPE

Religions are seldom complimentary about human nature. They typically identify a very serious condition from which escape seems difficult, even impossible. For Christians the predicament is sin – a condition inherited even before birth. Why can’t they lighten up and look at humanity’s good side? Why couldn’t God simply forgive Adam for his disobedience, as Muslims claim? And why did God, as Jews believe, create human beings with a good and evil inclination? Is there a way out and, if so, where to? Is it a heavenly paradise, a messianic age, or a world of love and justice?

1(A) DAN:

For Jews, the human predicament is rooted in human nature itself. Rabbinic literature teaches that there are two tendencies in every person: the good inclination (yetzer ha-tov), and the evil inclination (yetzer ha-ra). The good inclination urges each person to do what is right, whereas the evil inclination encourages sinful acts. At all times, a person is to be on guard against assaults of the yetzer ha-ra. It is not possible to hide one’s sins from God since God knows all things. In the words of the Mishnah (the earliest code of rabbinic law), “Know what is above thee – an eye that sees, an ear that hears, and all the deeds are written in a book” (Mishnah Avot 2:1). Thus God is aware of all sinful deeds, yet through repentance and prayer it is possible to achieve reconciliation with Him.

In rabbinic sources the yetzer ha-ra is often identified with the sex drive, which embraces human physical appetites in general as well as aggressive desires. Frequently it is portrayed as the force that impels human beings to satisfy their longings. To some degree, it resembles the Id in Freudian psychology. Human beings are thus engaged in a constant struggle with the evil within. For the Jew, there is only one cure to this universal malady: obedience to God’s will. The Talmud (a later code of rabbinic law) declares that the Torah is the antidote to the poison of the evil inclination. The implication is that when human beings submit to the discipline provided by the Torah, they are liberated from its influence. In this regard, the rabbis tell a story about a king who struck his son and subsequently urged him to keep a plaster on his wound. When the wound was protected in this way the prince could eat and drink without coming to harm. But if he removed the plaster, the wound would grow worse. For the rabbis the Torah is the plaster that protects human beings from their own sinful nature.

Rabbinic literature also teaches that this struggle is unending. All that one can do is to subdue it through self-control: no person can destroy it. Arguably such a view parallels the Christian concept of original sin, yet unlike Christian scholars, the rabbis interpreted Genesis 2–3 as simply indicating how death became part of human destiny. According to the rabbis death was the direct result of Adam’s disobedience. Although they did not teach a doctrine of original sin on this basis, they did accept “how great the wickedness of the human race had become on the earth, and that every inclination of the thoughts of the human heart was only evil all the time” (Genesis 6:5). They explain this by positing the existence of the evil inclination within every person.

In this context, the concept of repentance is of fundamental importance. Throughout the prophetic books sinners are admonished to give up their evil ways and return to God. According to traditional Judaism, atonement can only be attained after a process of repentance involving the recognition of sin. It requires remorse, restitution, and a determination not to commit a similar offence. Both the Bible and rabbinic sources stress that God does not want the death of the sinner, but desires that he return from his evil ways. Unlike Christianity, God does not instigate this process through grace; rather, atonement depends on the sinner’s sincere act of repentance. Only at this stage does God grant forgiveness and pardon.

This account of sin, law, and redemption would not be complete without saying something about the coming of the messiah. Traditional Judaism teaches that at the end of time, the king messiah will bring about the resurrection of the dead, the ingathering of all those Jews outside Israel to the Promised Land, and a golden age of human history. Clouds of glory will then spread over these returning exiles, and all humankind will be united in peace. This is the Jewish view of a hopeful future. I should stress in this connection that from the first century until the present, the Jewish community has rejected Christian claims about Jesus’ messiahship. Instead, strictly observant Jews pray for the coming of God’s anointed, a human king who will bring about the redemption of the world.

So far I have briefly outlined the central tenets of traditional Judaism as it evolved over the centuries. Yet, I should stress that non-Orthodox Jews do not fully subscribe to these doctrines about the human predicament and hope for the future. As I will explain later in much more detail, only the strictly Orthodox believe that all the Law in scripture and in rabbinic codes is binding. Further, the belief in messianic redemption has for many Jews seemed implausible in the light of scientific and secular knowledge. Nonetheless across the Jewish religious spectrum, the belief in humankind’s sinful nature and the need for redemption continues to play a central role in Jewish life.

1(B) GEORGE:

When the interfaith dialogue movement began, it tended to focus on points of similarity, probably because dialogue partners wanted to get to know each other, and because they felt that differences between religions were not quite as great as they had supposed. The time has come to move forward.

There is much in Dan’s exposition that strikes a chord. I agree that many Christians, if asked about such matters, would express a variety of views, while others would profess ignorance. We can also acknowledge important points in common: Jews and Christians share common scriptures, and both religions acknowledge sin and repentance as key concepts. Although the Bible does not explicitly mention sex in the Adam and Eve story, Saint Augustine and others have taught that humankind’s fall was bound up with sexual desire.

Some Christians, particularly Protestant fundamentalists, regard the story of Adam and Eve as a piece of literal history, explaining how sin entered the world. Others regard the story as symbolic and look to its spiritual meaning, namely that sin is endemic in human nature. Such a message may seem to paint an unduly black picture of humanity, reminiscent of the street preachers we still see occasionally with their sandwich boards proclaiming, “The wages of sin is death.” Such people no doubt give Christianity a bad name, and perhaps Christians could afford to emphasize the good side of human nature a bit more. Matthew Fox, in his Creation Spirituality, refers to “original virtue”, emphasizing the fact that God saw that his creation was “very good” (Genesis 1:31). However, Christian teaching draws attention to the way in which humans have marred God’s creation, and the Adam and Eve story highlights sin’s seriousness and its inescapability. One only has to glance at our daily news reports to be reminded of the prevalence of war, violence, crime, and poverty – all the results of sin.

So what is the remedy for sin? Dan suggests that it is obedience to the Jewish law. I think that Christians have at least two problems with this. First, most Christians do not see the point of obeying long lists of regulations about not boiling kids in their mother’s milk (Deuteronomy 14:21), not wearing garments that mix linen and wool (Deuteronomy 22:11), being circumcised, or avoiding pork and shellfish. The Gospels portray the Pharisees as being obsessed with this kind of detail, rather than with the spirit of the Law.

Second, Christians have long recognized the impossibility of fulfilling the Law. Early apostles like Peter wanted to retain the Jewish law, but the Bible recounts an acrimonious argument about this with Paul, in which Paul’s views prevailed (Galatians 2). Particularly in the Protestant tradition, Christianity has preached grace rather than works. This does not mean that one’s deeds are unimportant, as our subsequent discussion will make clear. What it does mean is that more than human effort is required to make one’s life acceptable to God.

Sin is the bad news. However, the word “gospel” means the opposite (“good news”), which is the assurance that sin and death can be – and have been – overcome. Regarding the Christian hope, Christians are less specific than Dan. The phrase “kingdom of God” occurs frequently in Jesus’ teaching. Its exact meaning has been much debated. Some Christians look forward to life in a supernatural realm, while others expect a renewed earth. The word “kingdom” is better translated as “rule”, and the concept therefore connotes a state in which human beings are subject to God’s sovereignty. According to Jesus’ teaching, acceptance of God’s rule can begin here and now within one’s heart (Luke 17:21), although the vast majority of Christians expect it to extend beyond death, after the resurrection.

I have to take issue with Dan on two important points concerning his “golden age”. First, I find it somewhat worrying that he should identify Jerusalem as its focus. If it involves repatriating Jews to this “Promised Land”, what is to become of the Palestinians? Has not this Jewish sense of entitlement to the land of Israel contributed to so much of the conflict in the Middle East and beyond? Second, Christians would agree that the messiah has an essential role in their final hope, but of course we would claim that he has already come in Jesus Christ – a topic we shall discuss more fully in subsequent chapters.

1(C) DAWOUD:

In the Qur’an God says, “O mankind, indeed We have created you from male and female and made you peoples and tribes that you may know one another” (49:13). In this there is both an acknowledgment of diversity and emphasis on the importance of knowledge of each other. As Dan and George have both emphasized, knowledge means not only identifying the things we agree on, of which there will no doubt be many, but also the areas where we must accept that we will always disagree.

On the whole it is probably true to say that the majority of Muslims have a general grasp of the key tenets of Islamic theology and law because they are familiar with the Qur’an and because the theology is so deeply entwined in the culture. I have a sense that while Western culture is permeated and patterned by its Judeo-Christian heritage in ways of which people are not always aware, Islamic theology is much closer to the surface of everyday life.

Muslims believe the Qur’an to be the literal and infallible word of God as revealed to the Prophet Muhammad and the duty of human beings is to obey its commands and injunctions and avoid those things that it prohibits. The core message of Islam is belief in one God, and the greatest offence is the ascription of any partners to God.

In the Qur’an, Adam is the first man and God commands the angels to bow down before His creation. The angels are created to obey God and have no free will, unlike mankind and the jinn. Iblis, described as one of the jinn whom God created from smokeless fire, defies God and refuses to prostrate himself before Adam, who is created from clay. Iblis is condemned to hell for all eternity, but persuades God to postpone his punishment until the Day of Judgment. Iblis makes it his purpose during this time to tempt mankind into sin, to whisper evil into the hearts of human beings; he is therefore identified with al-Shaytan or Satan.

In the Qur’an Adam and Eve are both tempted by Iblis to eat the forbidden fruit and they bear the responsibility equally. Having repented they are then forgiven by God and sent out of the garden to go forth and populate the earth. There is then no concept of original sin in Islam. The slate has been wiped and it is the responsibility of each individual to avoid sin in his or her own life.

Muslims believe that God sent His message to mankind through prophets of the past starting with Adam and including Abraham, Moses, Jesus, and many more of the biblical prophets. Islam is then the continuation and perfection of Judaism and Christianity. Muslims revere the prophets of the Bible, including Jesus, although they do not recognize him as divine and they deny his crucifixion and resurrection, claiming that God replaced him on the cross with a substitute. Muhammad is, however, the Seal of the Prophets, the last ever to be sent by God.

Muslims refer to the pre-Islamic period, particularly with the regard to life in the Arabian Peninsula at the time of the revelation of the Qur’an, as Al-Jahiliyya, the age of ignorance. Although the historical evidence does not entirely support the received view of this period, this is popularly understood to mean an age of idolatry and barbarity in which gambling, drunkenness, and sexual immorality were rife. Muslim belief is that Islam came to sweep all of this away and bring in a new era of peace and justice, although there is an alternative interpretation of the age of ignorance simply as a time of not knowing, that is, before mankind was made aware of the One God and His purpose for humanity.

For Muslims the purpose of creation is to worship God and obey His will. This begins with the profession of faith: “There is no God but God and Muhammad is the Prophet of God”, which is all that is required to be acknowledged as a Muslim. The word “Islam” itself means submission, specifically submission to the will of God. This does not mean the submission of the broken or oppressed but the act of faith in entrusting one’s life and destiny to God through following His law. Obedience to God’s law will bring eternal reward in the hereafter, while disobedience will result in eternal punishment. Both of these are graphically described in the Qur’an, although there is disagreement whether this is literal or metaphorical. There is no suggestion that Muhammad will return, but there is a popular belief based on an interpretation of a Qur’anic verse that ‘Isa or Jesus will return immediately before the Day of Judgment. There are also verses that refer to a gathering of the Children of Israel in the Promised Land in the Last Days, and some Muslims believe that the Ka’aba will be transported to Jerusalem for the gathering of the dead on the Day of Judgment. I am sure, however, that we will talk in greater depth about eschatology later on as well as our respective attachments to the Holy Land.

1(D) DAN:

In my last exchange, I stressed that modern Judaism in its various forms is very different from Judaism in previous centuries. The vast majority of Jews no longer feel obliged to accept the central tenets of the faith nor observe the manifold commandments in the Bible and rabbinic legal sources. Instead, most Jews feel free to select from the tradition those elements that they find spiritually meaningful. It should be remembered too that many Jews in Israel and in the diaspora (countries outside Israel) are totally secularized. Thus, in responding to the various points you both make about the human predicament and hope, I need to distinguish between the traditional Jewish view and modern theological interpretations of the Jewish heritage.

It is true as you both point out that Jews, Christians, and Muslims share the same scriptures. In the past Jews viewed the Torah (Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy) as divinely revealed to Moses on Mount Sinai. In this light, the account of Adam and Eve in Genesis was regarded as a true story about the origin of human beings (although it should be noted that some rabbinic exegetes rejected such fundamentalism). Today most Jews believe that the Torah (and the rest of scripture) is a mosaic composed of elements written by ancient Israelites over centuries of development. In this light the story of Adam and Eve is perceived as a myth – rather than a factual account.

This of course has important consequences for what you both say about human nature. George referred to the Christian belief in humankind’s fall as a result of Adam and Eve’s disobedience. Protestant fundamentalists, he points out, regard this narrative as literal history. Certainly most Jews today would reject such an idea, and view the notion of original sin as mistaken. As I pointed out in my previous exchange, it is not because of Adam and Eve’s rejection of God’s command that human beings are subject to sin, but because of human psychology: the inner struggle between the good and evil inclination is unending. For this reason, Jews would similarly reject the Islamic belief that Adam is the first man. Further, Dawoud’s description of Iblis tempting Adam and Eve to eat forbidden fruit in the garden (which parallels the account of the snake tempting Adam in Genesis) would be perceived as myth rather than historical fact.

Let me turn next to what George has said about Jesus. At the end of his exchange he notes that Christians believe that Jesus as messiah has a crucial role to play in humanity’s final hope. Here the paths between Judaism and Christianity diverge fundamentally. As I noted in my previous exchange, through the centuries Jews have a...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Praise

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Foreword by Marcus Braybrooke

- Preface

- A Word from the Authors

- Part I: Teachings

- Part II: Religious Practice

- Part III: Ethics and Lifestyle

- Part IV: Societal Issues

- Glossary

- Bibliography