- 352 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

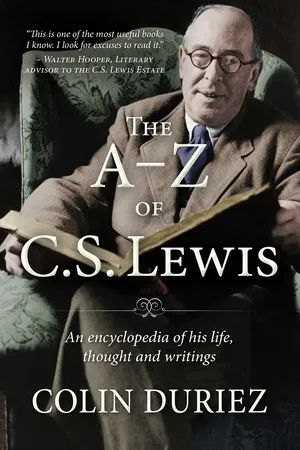

About this book

This fascinating volume brings together all the aspects of C S Lewis's life and thought.

It will delight anyone who is interested in C S Lewis and wants to learn more about him. Arranged in alphabetical order The A-Z of C S Lewis begins with The Abolition of Man - a book written in 1943 and described by Lewis as "almost my favourite" - to Wormwood, a character in The Screwtape Letters. Lewis's work is widely known and regarded, but enthusiasts are often only aware of one small part - his children's stories and his popular theology - and yet he wrote so much more, including science fiction and literary criticism. This is an enormously readable and attractive work that will be read time and time again.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The A-Z of C.S. Lewis by Colin Duriez in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literary Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

A

Abhalljin See: Aphallin

Abingdon A small town not far from Oxford* at whose nearby RAF base C.S. Lewis gave his very first talk on Christianity to wartime personnel of Bomber Command. He considered the experience an abject failure. Working at communicating more successfully in such talks helped him when the BBC* invited him to give national radio broadcasts, which were published and eventually collected into the bestselling Mere Christianity*.

The Abolition of Man (1943) C.S. Lewis considered this one of his most important books, a view that was shared by Owen Barfield*, who commented that it is “his most trenchant and valuable philosophic statement” and contains “much of his best and hardest hitting thought”. The small book is concerned with the education* of children, and in it Lewis developed his argument against what he saw as an alarming tendency in modern thinking. In a letter in 1955 he ruefully commented that The Abolition of Man “is almost my favourite among my books but in general has been almost totally ignored by the public”.

This powerful tract defends the objectivity of values like goodness and beauty against the already by then modern view that they are merely in the mind of the beholder, reflecting the social attitudes of a culture. Lewis argues that “until quite modern times all teachers and even all men believed the universe to be such that certain emotional reactions on our part could be either congruous or incongruous to it – believed, in fact, that objects did not merely receive, but could merit, our approval or disapproval, our reverence, or our contempt”.

If values are objective, argued Lewis, one person may be right and another wrong in describing qualities. If one says that a waterfall is beautiful, and another says that it is not, that “beautiful” does not merely describe emotions within the beholder. Only one of them is right; their opinions are not equally valid. A similar situation exists over the goodness or badness of an action. Judging goodness or badness is not simply a matter of opinion. Lewis argued indeed that there is a universal acknowledgment of good and bad over matters like theft, murder, rape, and adultery, a sense of what Lewis called the Way, or Tao*. “The human mind has no more power of inventing a new value than of imagining a new primary colour, or, indeed, of creating a new sun and a new sky for it to move in.”

Abandonment of the Tao spells total disaster for the human race, argued Lewis. Specifically human values like freedom and dignity become meaningless, he felt; the human being is then merely part of nature*. Nature, including humanity, is to be conquered by the technical appliance of science. Technology, with no limits or moral checks upon it, becomes totalitarian. An elite plans the future generations, and the present generation is cut off from the past. Such an elite is conceivably the most demonic example of what Lewis called the “inner ring”*, a theme he explored in an essay written in the war years and in his science fiction story That Hideous Strength*. It is a social and cultural embodiment of what, in an individual, would be deemed self-absorption and egoism.

Lewis elsewhere sums up the urgency of the point he makes in The Abolition of Man:

At the outset, the universe appears packed with will, intelligence, life and positive qualities; every tree is a nymph and every planet a god... The advance of knowledge gradually empties this rich and genial universe: first of its gods, then of its colours, smells, sounds and tastes, finally of solidity itself as solidity was originally imagined. As these items are taken from the world, they are transferred to the subjective side of the account: classified as our sensations, thoughts, images or emotions… We, who have personified all other things, turn out to be ourselves mere personifications. (“The Empty Universe” in Present Concerns, 1986)

In such thinking, the human being has become nothing. An objective morality, he concludes, is an essential property of our very humanity. See also: subjectivism

Adam and Eve in Narnia In the Bible*, Adam and Eve are the first humans, with all people in every part of the world descending from them. Narnia* is a land of talking beasts*, but humans are there from the beginning, having come from our world. The original humans who witness the creation of Narnia in The Magician’s Nephew* are Digory Kirke*; Polly Plummer*; Digory’s uncle, Andrew Ketterley*; and a London hansom cab driver, Frank*. Jadis*, late of Charn*, is also with them; it is through her that evil is introduced into Narnia at its very beginning. Frank is chosen to be the first king of Narnia by Aslan*. Aslan decrees that all kings or queens of Narnia have to be human (“Sons of Adam or Daughters of Eve”*), reflecting a hierarchy by which Narnia is ordered. Frank’s wife, Helen, is the first human to be drawn into Narnia by Aslan’s call. From Frank and Helen many humans, including future kings and queens, are descended, but other humans, the Telmarines*, stumble into Narnia through a portal, in this case a cave in a South Sea island.

Adonis In Greek mythology, a beautiful youth dear to the love goddess Aphrodite, mother of Cupid*. He is killed while boar hunting, but is allowed to return from the underworld for six months every year to rejoin her. The anemone springs from his blood. Adonis was worshipped as a god of vegetation, and known as Tammuz in Babylonia, Assyria, and Phoenicia. He seems also to have been identified with Osiris, the Egyptian god of the underworld.

Lewis was interested in Adonis, partly because of his respect for pre-Christian paganism*, and because the myth embodied the idea of death and rebirth explored in Miracles*. See also: myth became fact

The Aeneid of Virgil This classical epic poem was considered by Lewis one of the books that most influenced his vocational attitude and philosophy of life, and he partly translated it (see: reading of C.S. Lewis). Written between 29–19 bc, it embodies Roman imperial values in its Trojan hero, Aeneas. He is destined to found a new city in Italy. After the fall of Troy, the home-seeking Aeneas roams the Mediterranean with his companions. Making land in North Africa, he falls in love with Dido, Queen of Carthage. He later abandons her and establishes the Trojans in Latium, where the king offers him his daughter, Lavinia, in marriage. Turnus, a rival suitor, opposes him until killed in singlehanded combat. The poem builds upon a rich tradition of classical epics, including Homer’s Odyssey and Iliad.

Lewis read from his never-completed translation of The Aeneid to the Inklings*. The readings must have had a powerful effect, as the translation seems designed to be read aloud. What has survived, which was only recently discovered, has now been published, edited, with commentary, by A.T. Reyes. It includes all of Book 1, most of Book 2, much of Book 6, and fragments from the other Books of Virgil’s poem.

Further reading

A.T. Reyes, C.S. Lewis’s Lost Aeneid: Arms and the Exile (2011)

Aesthetica A southern region of the world in The Pilgrim’s Regress*, charted on the Mappa Mundi*. In it lies the city of Thrill.

affection See: The Four Loves

“After Ten Years” An unfinished piece published in The Dark Tower and Other Stories*. Lewis abandoned it after the death of Joy Davidman Lewis*. It concerns Menelaus (called “Yellowhead” in the story) and his wife Helen of Troy, after the Trojan War. The intended novel appears to reflect themes of love deepened by Lewis’s friendship with Charles Williams*, particularly the impact of Williams’s Descent into Hell* (1937). It would have carried on the exploration of paganism* most realized in Lewis’s Till We Have Faces*. Menelaus, it appears, would have had to choose between true love and an idealized image of Helen, as Scudamour has to choose between two Camillas in the flawed but powerful fragment “The Dark Tower”.

agape See: charity

Ahoshta An elderly Tarkaan and Grand Vizier in the Narnian* Chronicle The Horse and His Boy*. He is due to marry Aravis* in an arranged marriage. Baseborn, he works his way up the social hierarchy by intrigue and flattery. His appearance has little to attract the reluctant Aravis: he is short and wizened with age, and has a humped back.

Alambil One of the Narnian planets whose name means “Lady of Peace” in The Chronicles of Narnia*. When in conjunction with the planet Tarva* it spells good fortune for Narnia. See also: Narnia: geography

albatross In The Voyage of the “Dawn Treader”*, this large seabird leads the Dawn Treader* out of the terrifying blackness surrounding the Dark Island*, after Lucy Pevensie* calls in desperation to Aslan* for help. It is one of many signs of Aslan’s providence in Narnia*. There is a long maritime tradition of the albatross as guide and harbinger of good fortune (featured in Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner”).

Alcasan, Francois A distinguished radiologist in That Hideous Strength*. An Arab, Alcasan cut short an otherwise brilliant career in France by poisoning his wife. His severed head is rescued by the N.I.C.E.* after his execution on the guillotine and kept alive, perched on a metal bracket in a laboratory at Belbury*. He is (in Lewis’s grim joke) the head of the Institute, embodying its belief that the human body is now an unclean irrelevance in mankind’s evolutionary development, and revealing that physical immortality is a possibility. It is, in fact, uncertain that Alcasan himself has survived, because the macrobes, the bent eldila*, speak through his head, needing human agents for their devilish activities. He parallels the dehumanization of the Unman* of Perelandra*, illustrating Lewis’s belief in the gradual abolition of humanity in modern scientific society.

Alcasan’s bearded head wears coloured glasses, making it impossible to see his tormented eyes. His skin is rather yellow, and he has a hooked nose. The top part of his skull has been removed, allowing the brain to swell out and expand. From its collar protrude the tubes and bulbs necessary to keep it alive. The mouth has to be artificially moistened, and air pumped through in puffs to allow its laboured speech.

Mark Studdock* is introduced to the head as a sign of his deeper initiation into the N.I.C.E. Dr Dimble* speculates that its consciousness is one of agony and hatred. See also: The Abolition of Man

Aldwinckle, Elia Estelle “Stella” (1907–1990) While reading theology at Oxford* University, South African-born Stella Aldwinckle came under the influence of Lewis’s friend Austin Farrer*. In 1941, she became a member of the Oxford Pastorate, devoted to serving Oxford undergraduates. Later that year she founded the Oxford University Socratic Club*, choosing Lewis as its first president.

Alexander, Samuel (1859–1938) A realist philosopher who was important in the development of C.S. Lewis’s thought. Alexander was Professor of Philosophy at Manchester University, England, 1893–1924. He sought to develop a comprehensive system of ontological metaphysics, leading to a theory of emergent evolution. He proposed that the space– time matrix gestated matter; matter nurtured life; life evolved mind; and finally God* emerged from mind. His books include his Gifford lectures published as Space, Time and Deity in 1920. He later worked on aesthetic theory and wrote Beauty and...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Dedication

- Preface

- C.S. Lewis A–Z

- Bibliography of C.S. Lewis