- 96 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

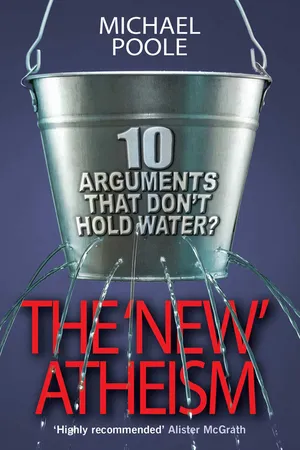

About this book

The new atheists are putting out new books and articles, bus adverts and TV programmes like there's no tomorrow. They've gained a large amount of public attention and media exposure - but do their arguments really hold water? Using the analogy put forward by the esteemed philosopher Anthony Flew, Michael Poole examines the new atheists' use of the 'ten leaky buckets' tactic of argumentation - presenting readers with a sum of arguments that are each individually defective, as though the cumulative effect should be persuasive. This closer look at the facts reveals that the buckets are, indeed, leaky.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The New Atheism by Michael Poole in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Christian Theology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Un-natural selection or ‘Down with sex!’

A1 Religion is evil because many bad deeds have been done by religious people.

In a two-part television documentary entitled Root of All Evil?1 Richard Dawkins selected many examples of odd, quirky or evil deeds associated with various religions in order to support his overarching thesis that ‘Religion is… bad for our children and it’s bad for you.’[R] To be fair, he later wrote that he disliked the title since no single thing, religion or otherwise is the root of everything. The programmes were criticized on the grounds that bad things being done in the name of religion doesn’t mean that all religion is bad. If he had taken different examples, such as the evangelical William Wilberforce and the abolition of slavery, the starting and foundation of schools and hospitals, or recent testimonies of religious believers forgiving appalling deeds against them and their families, one would have seen a different – and more balanced – view of religion.

In a radio interview Richard Dawkins fairly admitted, ‘I do think that’s a good point and in a way that’s a shortcoming of television that it’s almost forced to do that.’2 That may be, but by September of that year, his 400-page book The God Delusion was published, including many more negative examples.

Drawing the battle lines?

Dawkins made his purpose in publishing the book transparent, intending that ‘religious readers who open it will be atheists when they put it down.’[5]

Christopher Hitchens’ blunt message is along the same lines: ‘Religion poisons everything’ ‘Religion kills.’ Perhaps he should have qualified the word ‘everything’, in the same way that Dawkins qualified the word ‘all’ in the television title. It only needs one good deed to falsify ‘all’ and ‘everything’! Hitchens adds, ‘… the mildest criticism of religion is also the most radical and the most devastating one. Religion is man-made.’[10] This assertion is paralleled by Daniel Dennett, whose book Breaking the Spell starts from the assumption contained in his subtitle: Religion as a natural phenomenon. As with Dawkins, a delusion is envisaged, a spell to be broken, since it is assumed from the start that there is no transcendent Being, only natural factors. Actually, Dennett’s ‘spell’ turns out to be not one but two. Of the first he says, ‘The spell that I say must be broken is the taboo against a forthright, scientific, no-holds-barred investigation of religion as one natural phenomenon among many.’ The second ‘spell’ is ‘religion itself’.[18] It seems surprising that the first should be counted as a spell that needs breaking. Psychologists and sociologists of religion, themselves having religious beliefs or none, have long engaged in the scientific analysis of religious behaviour as individual and group phenomena. Applying the blanket term ‘scientific’ to such investigations merits a word of caution, for although the types of psychological and sociological investigation I refer to are scientific ones, the Science Curriculum of one country points out that ‘there are some questions that… science cannot address’.3

On truth

The truth, or otherwise, of the existence of God is one of these questions, a point considered further in Chapter 7. Investigators may choose to disregard the truth or falsity of religious beliefs while examining the function religious beliefs fulfil in the life of an individual or the structure of a society. But it must not be overlooked that the truth or falsity of the beliefs themselves is itself a valid and important study, even if it is not the immediate concern of the particular investigator. I wonder whether Dennett seems to be doing this by taking it for granted from the outset that religious beliefs about God must be false and can only have ‘natural’ origins, upon which he speculates.

The investigation of the functions served by religion – functionalism – is not, in principle, a threat to the truth-claims of religion. It is a partial, but valuable, study of one aspect of the behaviour of individual and collective humankind. Given Dennett’s beliefs, he suggests

The three favourite purposes or raisons d’être for religion are

- to comfort us in our suffering and allay our fear of death

- to explain things we can’t otherwise explain

- to encourage group cooperation in the face of trials and enemies.[102f.]

Religion serves these three functions, and why not? They say nothing about the truth or falsity of the beliefs themselves. Something that comforts us in suffering can also be true, for which we should be thankful; explanations outside the competence of science can also be true. Science cannot answer the question ‘Why is there something rather than nothing?’ but if God exists, it would be perfectly true and rational to say that God’s activity ‘explains’ it, something addressed in Chapter 6.

Anyway, whether there are ‘delusions’, ‘poison’ or ‘spells’, the claims of these books is clear: down with religion! But all religion? All aspects of all religions? How do these writers go about their chosen task? The first two authors have collected large quantities of reports of ugly or evil things that have been associated with religion in some way. Indeed, Hitchens says, ‘I have been writing this book all my life,’[285] and the quantity of bizarre stories he has amassed is large. Dennett also contributes a share but fairly comments that ‘The daily actions of religious people have accomplished uncounted good deeds throughout history, alleviating suffering, feeding the hungry, caring for the sick.’[253] But neither Hitchens nor Dawkins appears to have supplied a balancing list of good acts prompted by religious beliefs.

This strategy of trawling the human race for evil deeds associated with religion results in a bad argument for dismissing religion as evil. A similar point can be made about atheists – one need only look to the mass murders of Russian communism under Stalin, Cambodian communism (Khmer Rouge) under Pol Pot, and Nazism under Hitler – but that does not mean (and it would not be fair to claim) that all atheists are genocidal or amoral.

Sex

A different example may highlight why such argumentation is bad. Suppose someone collects all the bad stories associated with sex, produces page after page of stories about broken promises, rape, adultery, promiscuity, paedophilia, lust, bestiality and pornography, and concludes that sex is bad for you and sex poisons everything. What might a happily married husband and wife think? Both religion and sex involve powerful feelings, and, where these are abused, the results can be outstandingly vile. But, equally well, they can be outstandingly good.

So I agree with Dawkins’ and Hitchens’ revulsions over the horrors of ‘Harmful religion’. I am not defending such things; I agree with much of what they say. Neither am I giving blanket approval to every practice of all religions. Each must ‘stand before the bar’ for itself. People need to assess where truth lies.

Need for discernment

‘Harmful religion’ has much to repent of, including such Christian corruptions as the Crusades. In this example, a key question is: if something claims to be Christian, does it meet the criteria of its founder? Forgiveness is a key factor in Christianity, though not exclusively so. Furthermore, Jesus is reported as saying

My kingdom is not of this world. If it were, my servants would fight to prevent my arrest by the Jews. But now my kingdom is from another place (John 18:36).

By their fruit you will recognize them. Do people pick grapes from thornbushes, or figs from thistles? Likewise every good tree bears good fruit, but a bad tree bears bad fruit (Matthew 7:16–17).

In short, he is saying: if people don’t do (or try to do, since we are all fallible) what I teach, don’t believe them if they claim to have faith in me and to be one of my followers.

As to what ‘faith’ is, that is the subject of the next chapter.

CHAPTER 2

‘Faith is believing what you know ain’t so’

A2 ‘Faith is irrational’[R] and ‘demands a positive suspension of critical faculties.’[R]

A well-known radio interviewer provocatively said that ‘science is based on evidence… and religion is, by definition, a matter of faith’, something echoed in the title of this chapter by Mark Twain’s famous ‘schoolboy’ quote. Views like this are all too common as can be seen from the following quotations: ‘Religion is about turning untested belief into unshakeable trust’ ‘Religious faith discourages independent thought’ ‘The process of non-thinking called faith’ ‘If we can retain our faith against the evidence, in the teeth of reality, the more virtuous we are.’[R] Hitchens comments:

If one must have faith in order to believe something, or believe in something, then the likelihood of that something having any truth or value is considerably diminished. The harder work of inquiry, proof, and demonstration is infinitely more rewarding …[71]

… let the advocates and partisans of religion rely on faith alone, and let them be brave enough to admit that this is what they are doing.[122]

In Professor Dennett’s view, people ‘believe in belief’, while, for Professor Grayling, ‘Faith is a commitment to belief contrary to evidence and reason.’1

So, then, are the many religious academics involved in the sciences, some Fellows of the Royal Society, some knighted, using Dawkins’ words, ‘dyed-in-the-wool faith-heads’, ‘immune to argument’, suffering from ‘childhood indoctrination’, not ‘open-minded’, ‘whose native intelligence’, by contrast with ‘free spirits’, has not been ‘strong enough to break free of the vice of religion’?[5f.]

In a couple of words, it is being claimed that faith is unevidenced belief. But we already have a word in the English language that precisely encapsulates those qualities, and that is ‘credulity’. So why not use it, rather than confusing it with ‘faith’?

It is puzzling to see where this cluster of idiosyncratic ‘definitions’, these caricatures of faith, come from. How many religious believers would recognize any of them as remotely describing their own position? Are we being misled by what philosophers call ‘stipulative definitions’, in the hope that, if they are uttered often enough, we will believe them?

Faith as ‘trust’

The above views of faith do not reflect how the word is generally used in everyday life. In common parlance, we might express our faith in a surgeon, a close friend’s reliability, a particular medicine, a bungee rope and the integrity of a husband/wife.

Of course, faith can turn out to be misplaced, even though sincerely held. Sincerity, though praiseworthy, is not enough. Someone might take from their garden shed a bottle of what they sincerely believed was water, to extinguish the glowing charcoal of a spent barbecue. But their sincerity would not help if the colourless liquid in the bottle was petrol for the lawnmower. Or again, until recently most people would have sincerely believed that faith in a bank’s secure keeping of their savings was beyond question.

So, what about Dennett’s phrase about having ‘faith in faith’? Could one then have faith in faith in faith? Somehow these phrases sound linguistically odd. That is because ‘faith’ is a word that cannot stand alone. Faith has to be in something or somebody, and the reliability or otherwise of the object of faith is of key importance.

A group of Scouts constructed a rope bridge across a river. Pleased with what they had done, they had enough faith in their efforts to believe they could safely cross the river. and they were not disappointed. But this act of faith drew upon earlier experience, perhaps of failures, knowing about the required thickness of the ropes and the best positioning of the guy-ropes. Similarly, faith in entrusting our lives to an anaesthetist draws on some understanding of medical practice and the testimonies of those who have come safely through operations under general anaesthetics.

So, wh...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- About this book

- Chapter 1 Un-natural selection ‘Down with sex!’

- Chapter 2 ‘Faith is believing what you know ain’t so’

- Chapter 3 People who live in glass houses…?

- Chapter 4 ‘…and may be used in evidence’?

- Chapter 5 Ancient.doc

- Chapter 6 Explaining explaining

- Chapter 7 Where do we draw the boundary?

- Chapter 8 An endangered species?

- Chapter 9 Back to the drawing board – but whose?

- Chapter 10 Unpeeling the cosmic onion

- Summary

- Notes