- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

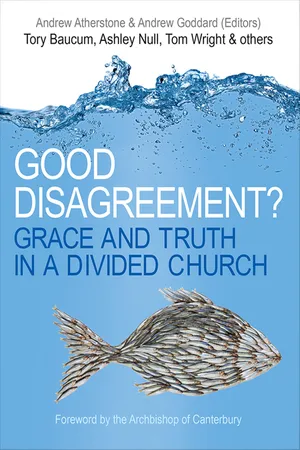

About this book

At every level of church life from the local congregation to worldwide denominations, Christians can find themselves in turmoil and divided over a range of important issues. Many conclude that harmony is not achievable, and never will be. Can we, as Archbishop Justin Welby has asked, transform 'bad disagreement' into 'good disagreement'? What would that look like in practice? This book is designed to help readers unpack the idea of 'good disagreement' and apply it to their own church situations. It doesn't enter into specific contentious debates, but instead considers issues such as reconciliation, division, discipline, peacemaking, mediation and mission. It asks what needs to happen for those from differing viewpoints to both listen and be heard, and does not shy away from hard questions about unity in the gospel and the church's public witness. The book draws lessons from the New Testament, church history, and contemporary experience, with chapters from a dozen theologians and practitioners. They are editors Andrew Atherstone and Andrew Goddard, Tory Baucum, Martin Davie, Lis Goddard, Clare Hendry, Toby Howarth, Ashley Null, Ian Paul, Stephen Ruttle, Michael B. Thompson, and Tom Wright.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Good Disagreement? by Andrew Atherstone,Andrew Goddard in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Christianity. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Disagreeing with Grace

Andrew Atherstone and Andrew Goddard

The history of the church is marred by violent and vociferous disagreements between professing Christians. Even the apostles use language which shocks modern readers, though they also teach grace and gentleness in the midst of conflict. What does it mean to disagree with grace? Shall we simply “agree to disagree”? What about the essentials of the Christian message? This introductory chapter sets the scene for the rest of the book, exploring the language of “good disagreement”. It appeals for greater theological clarity, for the significance of individual disputes to be carefully distinguished, and for the church to demonstrate grace in all things.

Insult me again!

One of the most entertaining and also sometimes disturbing theology websites on the Internet is the Lutheran Insulter.1 It randomly selects an insult from the writings of the great Protestant reformer Martin Luther and then gives you the chance to request “Insult me again”. All of the insults are fully referenced from Luther’s Works. Some are simply childish (“Snot-nose!”), even if presenting amusing similes (“You are like mouse-dropping in the pepper”). Some are highly personal: writing on marriage Luther exclaims, “Go, you whore, go to the devil for all I care.” At times he calls down God’s wrath on those with whom he disagrees, especially in his writings against the Roman papacy where he is at his most vehement with challenges such as “May God punish you, I say, you shameless, barefaced liar, devil’s mouthpiece, who dares to spit out, before God, before all the angels, before the dear sun, before all the world, your devil’s filth.” Little wonder the site’s designer admits, “I, a Lutheran myself, neither approve of nor condone Luther’s insults as appropriate for modern theological discourse, nor most modern discourse for that matter. Some of his insults are inexcusable; a few are so crass as to make me reluctant to put them on this site.”

These examples starkly remind us that throughout the history of God’s people there have been many instances of “bad disagreement”, sometimes involving Christian leaders who nevertheless remain widely respected. Abusive language is only the tip of the iceberg. At their worst – not least during the Reformation – theological disagreements between professing Christians have led beyond violent speech and personal insults to physical intimidation, exile, and imprisonment, even to brutal torture and execution. Five Archbishops of Canterbury have died violently, lynched by the mob, burned at the stake, or beheaded by the axe-man, which has prompted the current archbishop, Justin Welby, to reflect that, mercifully, the worst he has to face is “execution by the daily newspapers”.2 Some divisions between Christians are extremely ancient, propped up by a lengthy list of historic grievances. Competing groups of Orthodox monks (Greek, Armenian, Coptic, Ethiopian, and Syriac) share jurisdiction of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem, and the brawls and fist fights between them over apparently petty squabbles have become a regular source of amusement for the world’s media, but reveal the deeper pain of broken relationships and disagreements handled badly.

The violence of disagreements within the church today – as seen everywhere on the blogosphere – is part of a centuries-old narrative. Professing Christians seem to have an endless capacity for caustic commentary, character assassination, mutual suspicion, and the gushing forth of vitriol, which are signs of a distressing spiritual malaise. As Jesus himself says, “out of the abundance of the heart the mouth speaks” (Matthew 12:34). These internecine hostilities are a public scandal and damage the witness of the church. Christians preach a gospel of grace, but in their own relationships too often demonstrate graceless factionalism. As a result, a watching world grows disillusioned.

Is it possible to transform disagreements within the church from “bad” to “good”? What would it look like for Christians to disagree with grace and to turn cursing into blessing? Can we model relationships which the world finds attractive and countercultural? These are not inward-looking questions for the Christian family, but have massive missional implications.

Christ the controversialist: full of grace and truth

Before you rush to judge the shocking language of theologians like Martin Luther, pause to consider the polemic of the New Testament itself. The apostles never condone physical violence or coercion; rather they call upon believers to suffer with patience for the sake of the gospel, like their Saviour who when reviled did not revile in return (1 Peter 2:23). But when rebuking error they do use extremely strong language, which startles modern readers.

The apostle Paul chastised new converts in Galatia for “deserting the one who called you to live in the grace of Christ” and “turning to a different gospel which is really no gospel at all”. He accused some of “trying to pervert the gospel of Christ” and placed them – along with anyone who copied them – “under God’s curse” (literally, anathema). Later he expressed his wish that such people would go beyond advocating circumcision and “emasculate themselves” (Galatians 1:6–9; 5:12). And this is not just a one-off aberration from the apostle. He warned believers in Philippi to watch out for “those dogs, those evildoers, those mutilators of the flesh”, describing them as “enemies of the cross of Christ” whose “destiny is destruction, their god is their stomach, and their glory is in their shame. Their mind is set on earthly things” (Philippians 3:2, 18; NIV).

Indeed, the New Testament never uses soft words for those who lead God’s people away from the gospel. Its language would often fail our contemporary tests for “good disagreement”:

- “May your money perish with you… You have no part or share in this ministry, because your heart is not right before God” (Acts 8:20; NIV).

- “These people blaspheme in matters they do not understand. They are like unreasoning animals, creatures of instinct, born only to be caught and destroyed, and like animals they too will perish” (2 Peter 2:12; NIV).

- “Certain individuals whose condemnation was written about long ago have secretly slipped in among you. They are ungodly people, who pervert the grace of our God into a license for immorality and deny Jesus Christ our only Sovereign and Lord” (Jude 4; NIV).

- “Any such person is the deceiver and the antichrist” (2 John 1:7).

- “a synagogue of Satan” (Revelation 2:9).

John the Baptist assaults the religious leaders as “You brood of vipers” (Matthew 3:7 and Luke 3:7). But most surprisingly, Jesus himself uses identical language: “You brood of vipers, how can you who are evil say anything good?”, “You snakes! You brood of vipers! How will you escape being condemned to hell?” (Matthew 12:34; 23:33; NIV). He pronounces woes on his opponents whom he describes as “blind guides”, “blind fools” (moroi in Greek, from which we get the word “moron”), and “whitewashed tombs” (Matthew 23:16–17, 27). In John’s Gospel, Jesus confronts those who oppose and reject him with the words, “You belong to your father, the devil, and you want to carry out your father’s desires” (John 8:44; NIV). Such strong language can even be directed at his closest followers, as in his rebuke to Peter: “Get behind me, Satan!” (Mark 8:33; NIV).

So within Scripture the boundaries of how we express “good disagreement” do not always fall where we might expect. Some of this can be explained – as with Martin Luther – by setting these specific examples in their wider literary context and also the culture of the time and its particular standards and patterns of rhetoric and polemic, which are different from our own. There is, however, an important principle driving such strong approaches to disagreement. It is one to which we perhaps give less attention in our postmodern context where pluralism and relativism are such powerful forces: gospel truth matters and is a blessing to the world, so should be defended against errors that obscure the gospel and can be seriously detrimental for people’s spiritual health. Error is dangerous and needs to be strenuously resisted and named for what it is – a powerful force that opposes the God of truth and threatens to damage the life and mission of the church.

In his classic study Christ the Controversialist John Stott writes:

In our generation we seem to have moved a long way from this vigorous passion for the truth displayed by Christ and his apostles. But if we loved the glory of God more, and if we cared more for the eternal good of other people, we would surely be more ready to engage in controversy when the truth of the gospel is at stake. The command is clear. We are to “maintain the truth in love” [Ephesians 4:15] – being neither truthless in our love, nor loveless in our truth, but holding the two in balance.3

The apostle Paul also warns us to have nothing to do with “foolish and stupid arguments because you know they produce quarrels” (2 Timothy 2:23; NIV), on which Stott comments:

There’s something wrong with us if we relish controversy… Controversy conducted in a hostile way, which descends to personal insult and abuse, stains all too many of the pages of church history. But we cannot avoid controversy itself. “Defending and confirming the gospel” [Philippians 1:7] is part of what God calls us to do.4

Nevertheless, this passion for truth must always be deeply imbued with grace, because Jesus Christ himself embodies both grace and truth (John 1:14). The letters of the apostle Paul, despite his reputation for straight-talking, are also shot through with grace and gentleness. He is clear that there are ways of disagreeing and patterns of conflict which, although they arise among believers, have no place in the Christian community. To the Galatians he warns that “if you bite and devour each other, watch out or you will be destroyed by each other”; and counsels that “if someone is caught in a sin, you who live by the Spirit should restore that person gently” (Galatians 5:15; 6:1; NIV). Similarly in Philippians his attack upon opponents in chapter 3 is sandwiched between a call for the church to imitate the humility of Christ (chapter 2) and a plea to two Christian women, Euodia and Syntyche, to put their disagreement aside and “be of the same mind in the Lord”, calling on the wider church to help them in doing this (chapter 4). In Romans, Paul calls on believers to “accept the one whose faith is weak, without quarrelling over disputable matters”. In response to these disagreements he asks, “Who are you to judge someone else’s servant?” and urges, “Let us therefore make every effort to do what leads to peace and to mutual edification” (Romans 14:1, 4, 19; NIV). He exhorts the Ephesians to live in a manner worthy of their Christian calling, “with all humility and gentleness, with patience, bearing with one another in love, eager to maintain the unity of the Spirit in the bond of peace” (Ephesians 4:2–3; ESV).

In his final letters, preparing the next generation of leaders, Paul remains clear on the imperative to uphold and defend the truth, but also the need for care in handling and distinguishing between different types of disagreement. Grace and gentleness remain a keynote. To Titus, he writes that believers should be “peaceable and considerate, always gentle toward everyone” (Titus 3:2; NIV). To Timothy he gives similar instructions:

The Lord’s servant must not be quarrelsome but must be kind to everyone, able to teach, not resentful. Opponents must be gently instructed, in the hope that God will grant them repentance leading them to a knowledge of the truth, and that they will come to their senses and escape from the trap of the devil, who has taken them captive to do his will. (2 Timothy 2:24–26; NIV)

Timothy is told to pursue both “righteousness” and “gentleness” (1 Timothy 6:11). Patience and gentleness are both part of the fruit of the Holy Spirit (Galatians 5:22–23), and reflect the character of God who “is patient with you, not wanting anyone to perish, but everyone to come to repentance” (2 Peter 3:9; NIV).

A biblical approach to “good disagreement” in the contemporary church needs to hold together these different strands of the New Testament witness. When Christians are shaken by the disagreements that sometimes drive at the heart of belief and discipleship, can we hold firmly to a life of both grace and truth? Of righteousness and gentleness? What does that look like in practice?

Agreeing to disagree

Faced with disagreements in the church, Christians frequently polarize into two camps, one stressing “truth” and the other stressing “grace”. The first camp rejects the possibility of maintaining fellowship across our disagreements, insisting that the only proper response is continued disputation, defending truth, combatting error, and some degree of division or separation. The second camp claims that Christian agreement is unobtainable, perhaps even undesirable. Instead it welcomes diverse views and practices within the church, to be tolerated and perhaps even celebrated, often with the motto “Let’s agree to disagree”.

“Agreeing to disagree” is not a postmodern, relativist invention, but has a long Christian heritage. George Whitefield, the eighteenth-century evangelist, was an ecumenist at heart. An Anglican by ordination and inclination, he travelled thousands of miles across Britain and North Am...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Contributors

- Foreword

- 1. Disagreeing with Grace

- 2. Reconciliation in the New Testament

- 3. Division and Discipline in the New Testament Church

- 4. Pastoral Theology for Perplexing Topics: Paul and Adiaphora

- 5. Good Disagreement and the Reformation

- 6. Ecumenical (Dis)agreements

- 7. Good Disagreement between Religions

- 8. From Castles to Conversations: Reflections on How to Disagree Well

- 9. Ministry in Samaria: Peacemaking at Truro Church

- 10. Mediation and the Church’s Mission

- Notes