- 368 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The average age of churchgoers in Britain is now 47. Almost every denomination is experiencing steady decline. How sure can we be that we are still offering something people want to hear? Alison Morgan identifies four clear reasons to be confident: 1. The gospel still speaks to confused teens and weary sceptics. By embracing doubts and welcoming questions it remains open to us to present something which answers people's real needs. 2. The word of truth and the Spirit of power still exercise authority and compel attention. Alison's own experience of ministry in the UK and abroad provides illustrations. 3. Spiritual gifts, given not to excite individuals but in order to renew the church for its core task of mission, are powerfully present and widely recognised and practised. 4. In a time of rapid cultural change, new expressions of church are constantly emerging: this is necessary to guard against vital spirituality sliding into drab religion.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Word on the Wind by Alison Morgan in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Christian Ministry. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

A Confident Gospel

Chapter 1

Understanding the issues

It’s possible to live in a place and not notice the changes which take place all around you. Sometimes we don’t notice because there are so many of them that only the biggest and boldest stand out. Everyone noticed Canary Wharf as it thrust its way into the skies of London, its summit winking red in the sunlight to warn low-flying aircraft of its sudden intrusion into their domain; but few observed the quiet passing of a row of old brick terraced houses in nearby Greenwich, or the careful fencing of an ancient oak in the park. And sometimes we don’t notice because change comes to a place slowly, imperceptibly: a new sign here, a freshly weeded garden there – minor things compared with the passing of the seasons with their shifting shapes and colours, and mere human wrinkles on the surface of a world which is itself in constant motion.

The city of Leicester is the first kind of place. I lived there for eighteen years, and watched the redevelopment of the river with its new university buildings and waterside plazas, the shiny silver rising of the National Space Centre beside the old Abbey Pumping Station, the sleek arrogance of the windowless casino built in curious anticipation of changing legislation. And yet other things I did not notice. One of these was the Holiness Chapel. Despite its location on the London Road, the old Victorian artery leading from the southern suburbs down into the city centre, and despite its fluorescent green poster proclaiming that those who wait upon the Lord shall renew their strength, the Holiness Chapel remained curiously unobtrusive. Until one day in 2006 a large notice went up: For Auction.

I looked it up. Properly known as Thanksgiving Hall, the chapel opened in 1925 as the first building of the Independent Holiness Movement, a charismatic renewal movement of which Leicester became the founding centre and which was to spread all over the United Kingdom. I was not the only person to have failed to notice it; although meetings were still being held there, those occupying the buildings on either side were unaware of them. One report noted that ‘No recruitment or ecumenical initiatives have ever been known.’ The chapel was sold for £500,000 and is now home to the halal Al Mashriq restaurant, whose owners are happy to comply with the clauses written into the documents of sale which forbid drinking, gambling, and lap dancing.

And yet this quiet, nondescript building had been, in its heyday, the thriving headquarters of a national renewal movement. ‘God First’, proclaims a carving over the door. It became, for me, something of a symbol: the symbol of a church which failed to adapt, and perhaps more widely of a society in which the Christian faith is in decline. What happened to these people who believed that those who wait upon the Lord shall renew their strength, and yet who seemingly disappeared without trace in little more than a generation or two? And will that same thing happen to us, so that what even today seems alive and vibrant will tomorrow look like the established habit of a bygone era?

It is often said that we must change in order to remain the same. What may appear static rarely is; even the ground on which we stand is spinning, despite all apparent evidence to the contrary, at an alarming rate beneath our feet.1 Leicester’s motto is ‘Semper eadem’ – ‘always the same’. And yet of course Leicester has not been always the same. Turn back the pages of its history and you find a Celtic tribal settlement, Roman baths, a Norman castle, an Augustinian abbey, and grand new Victorian parks. Its streets have been at different times full of sheep, of fighting Parliamentarians and Royalists, of ragged factory workers, of the carriages of comfortable Victorian middle-class families, and of Gujurati-speaking immigrants. Today Leicester is home to seventy language groups and many religious faiths. Stay the same and you will find that everything changes around you, that the rushing waters will sweep on and leave you high and dry; that you leave no greater trace than that left by the faithful members of the Independent Holiness Movement.

I work now for ReSource, a small but ambitious charity whose aim is to support ordinary churches as they seek to minister confidently and effectively in a changing context. Sometimes it is hard to know what should change and what should remain the same; hard to know how to keep a constantly sharpened cutting edge whilst remaining faithful to a shared history which goes back 2,000 years. Some of us in the church seem to want change for change’s sake – is it possible to be authentically Christian in today’s society without an amplification system, a youth band, a programme of social engagement? Others of us resist change doggedly, as if our faith somehow resides in the medieval flagstones, seventeenth-century liturgies or Victorian pews of buildings, which in fact mostly date from well over a thousand years after the death of Jesus. To change or not to change easily becomes an argument about style, the style not of our discipleship but of our gatherings. It’s all very confusing.

Over the last seven years ReSource has worked in dioceses, deaneries, and local churches, with Anglicans, Baptists, Methodists, Catholics, and New Church denominations all over the country. For me it’s been a fascinating process, after years given primarily to writing and ministry in a single parish. What is the issue the church finds most difficult today? Tim Sledge put his finger on it as we ate sandwiches together in Northampton. It’s confidence. We live in a culture which dents and knocks our confidence as Christians. And so ‘does this stuff really work?’ is probably the question to which most ordinary Christians in this country would like to hear a convincing answer. It’s expressed in different ways, but whether people are asking us to help them to know how to find ways of reaching out to others, or to deepen their relationship with God, or to pray for healing, what they really mean is perhaps just this: can we actually have confidence in this ancient faith of ours? Do we really have something which people out there need and want – or not?

I think we can answer that question in two very different ways. Firstly, we can answer it through experience – it has changed me; let it change you. We all have our own story to tell, and it is important that we tell it; the good news is not just something we believe but something we live – it changes us, and therein lies its power, its attractiveness, its uniqueness. We are not those odd people with a peculiarly antiquated sense of how to have a good time on a Sunday morning, we are – or should be – living witnesses to the power of God to bring healing and transformation to ordinary lives.

Often I meet people who have encountered Jesus in this way. I think of Kevin, who told me he’d just become a Christian. How did that happen? I asked. Kevin is an ordinary bloke, an odd job man, not very articulate. He didn’t want to tell me, he said; it’d cause a riot. No, go on, I said. Kevin explained that his life had been in a mess. His wife had run off with another man and he’d been forced to find himself lodgings. He was having nightmares – dark figures running towards him, with faces like the face in The Scream, he said, twisting his face into a contorted, open-mouthed expression of anguish. One night Kevin was having this nightmare, and suddenly he was aware of another figure, and a great sense of being overwhelmed by love. He woke up. “I thought it was a woman,” he said. “I thought it meant I was going to find another woman. I’ve only ever known that kind of love with a woman – but this was different. I can’t describe it, but it was bigger, much stronger.” The couple he was lodging with were Christians. Kevin realised the figure offering him this love was Jesus. He’s a rough and ready kind of guy, not the kind of guy you’d expect to find in church. But there he was, three weeks later, talking about how love is the only thing that matters.

But important and encouraging though Kevin’s story is, it’s not enough. If we have no story to tell, perhaps we have not yet grasped the full potential of what is available to us in Christ. But even if we have, we need to be able to look critically at the bigger picture. So secondly, we need to be sure that we are talking not just about our own experience, something that worked for me but might not work for you, but about something universal; something much bigger, something into which our individual stories fit like pieces of a jigsaw. To do this, we need to be able to understand and respond with confidence to some of the intellectual challenges our culture throws up to the gospel, to know why and how it is that we genuinely do have something powerful and true to offer. We need to be able not just to encourage those around us with our real life stories, but also to help them through the tangle of voices which press in on all of us, voices which offer illusory and ultimately unsatisfactory answers to the big questions of human existence. In many places that’s just what’s happening. In others it is, as yet, not.

What stops us? Many things, of course, but I think that two in particular erode our confidence. The first is to do with the church itself, and in particular with our experience of steady numerical decline. Falling numbers are not good for morale, and in particular they are not good for the morale of church leaders. The second is to do with the fast-changing cultural environment in which we live, and the wide acceptance of values which are in direct conflict with those of the gospel. These all too easily slip under the radar of ordinary Christians who do not have the skills or theological experience to evaluate them, and who therefore find themselves giving in to the invisible pressure to conform to the norms which surround us, or subsiding into an unwilling but confused silence. To put it another way, we are so unnerved by Richard Dawkins – who is not interested in the possibilities of the gospel – that we fail to offer it to Kevin, who is.

Life on board the Titanic

Perhaps the biggest challenge to our confidence comes from the visible weekly reminder that church is losing its appeal; such is the scale of the problem that statistician Bob Jackson warns that the figures should not be read by those of a nervous disposition. The basic facts are these. Peak attendance in the UK in the twentieth century was in the year 1904, when 33% of adults were to be found in church on any given Sunday; this already represented a steep decline since the mid-nineteenth century. By 2006 weekly attendance had fallen to just over 6% (see Figure 1). Membership of the Church of England declined by 14% in the 1990s alone (28% for children).

Figure 1: Proportion of UK population in church on a typical Sunday.

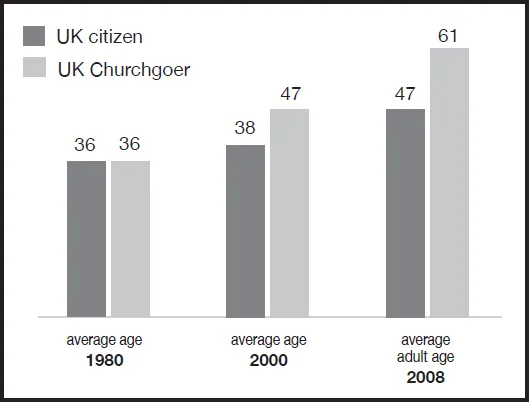

Figure 2: Rising average age of UK Churchgoers compared to the national average (2008 figure relates to the C of E).

Some denominations are doing a little better than that, others a little worse. The average age of churchgoers in all denominations is rising: in 1980 it was 36 (the same as the national average), but by 2000 it was 47 (compared to 38 nationally). The most recent figures available for the Church of England relate to the year 2008, and show that the average adult Sunday Anglican is now 61 years old (compared to 47 in the general population), and that two thirds are female (see Figure 2). Half of all Anglican churches have no work amongst children and young people, and only one in three hundred 18–24 year olds now attends a weekly Church of England service.2 Whilst thousands of young people gather each year at the inter-denominational Soul Survivor and Momentum events in Somerset, they come from a tiny minority of mostly urban churches, and represent a fraction of their generation. It’s a small community – my son Edward was one of 3,500 students attending Momentum last year; expecting anonymity, he reported the curious experience of constantly bumping into people he knew from all over the country. And it’s not just the overall numbers but, more worryingly, the proportion of young people in church which is shrinking. Often it’s not so much hostility to the gospel as ignorance of it. I was talking recently with Eleanor, a vicar in Carlisle. Eleanor had just been approached by a woman who wished to have her baby baptised. What do you know about God, Eleanor had asked gently. “Well, nothing really.” What about Jesus, then, do you know anything about him? “Well, no, not really.” Looking for common ground, Eleanor suggested she did know something about Jesus, because she knew about Christmas. “Oh yes, I suppose I do,” said the woman, furrowing her brow in puzzled thought.3

Meanwhile those who do know these things continue to leave – the fastest growing sector of the Christian community is said to be those Christians who no longer attend church. A recent survey concludes: ‘Britain is currently experiencing an unprecedented cultural and social change. The nation, Christian, at least in theory, for the last 1,300 years is demonstrably no longer so. The last fifty years have seen churches empty, the Christian worldview cannibalised and abandoned, Christian institutions lose their historic influence, and the birth of generations almost completely ignorant of the Christian story.’ It has been suggested that if the current rate of decline continues, there will be no institutional Christian presence in this country by 2050.4

With the best will in the world it’s hard to feel positive about these statistics. Lesslie Newbigin remarked long ago that the Christian faith is now regarded as ‘a good cause in danger of collapsing for lack of support.’ The Bishop of Durham has written that it’s seen as ‘an upmarket version of day-dreaming for those who like that sort of thing.’ And that’s the charitable view. A member of a lively church in Maidstone suggested more robustly that ‘the church has done for Jesus what Jaws did for swimming lessons.’5 Whatever the cause, public interest in church is probably at its lowest ever point. Church leaders who try to reverse the trend by dint of sheer hard wor...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Praise

- Dedication

- Contents

- About the Author

- Acknowledgments

- Foreword

- Introduction

- Part I: A Confident Gospel

- Part II: The Tools of Our Trade

- Part III: Doing Things Differently

- Appendix: Further resources

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index