![]()

1

THE WORLD OF JESUS’S FIRST FOLLOWERS

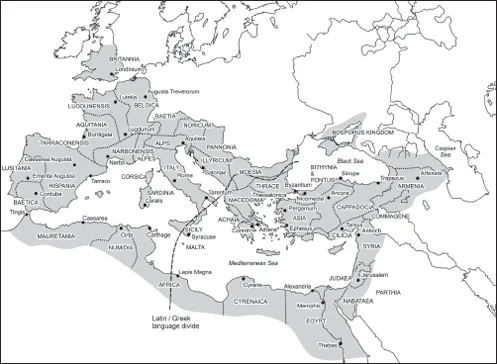

The Roman Empire

The first followers of Jesus lived in a world in which there was only one real political, military, and economic superpower—Rome. The Roman Empire encompassed almost the entire Mediterranean region and spanned vast tracts of three of the world’s continents. In the first century, Rome’s territory extended from the shores of the English Channel in the north1 to Egypt in the south, from the straits of Gibraltar in the west to Mesopotamia in the east. It covered all of Europe south and west of the Rhine and the Danube, much of North Africa, and a large swathe of Asia Minor, as well as Syria and Palestine. This empire constituted the whole of the civilized world; outside of it lay only barbarian or desert regions, subject, as far as Rome was concerned, to forces of lawlessness and savagery.

A system of rule over the whole of this territory by a single individual was created by the great-nephew of Julius Caesar, Octavian, who came to be known as Augustus (31 B.C.–A.D. 14).2 Adapting structures and terminology inherited from the Roman Republic (established ca. 509 B.C.), Augustus had set up a regime in which ultimate political authority rested squarely in the emperor’s hands. A formal configuration of traditional decision-making bodies such as the Roman Senate continued, and the running of the empire naturally required a bureaucratic apparatus, but the emperor himself held final control over the armies, the diplomatic channels, the fiscal system, and the public finances. In reality, the whole system was a huge military dictatorship, sustained by vast armed might and presided over by a figure who, although he eschewed the title of “king,” had absolute power and whose commands amounted to law.

The Roman Empire around the middle of the first century A.D.

The great majority of the empire’s inhabitants lived in the countryside, but, as in most societies, political power was concentrated in the cities. Rome itself had three-quarters of a million or more inhabitants, and it was in every sense the capital of the civilized world. It was the city like no other: the home of the gods, the heart of government, and the center of cultural sophistication. In the second quarter of the first century, the next most important place was Alexandria in Egypt, which had possibly 400,000 residents, followed by Ephesus with around 200,000, and Antioch with perhaps 150,000. Most other cities, such as Corinth, Sardis, and Carthage, had populations of little more than 100,000 to 120,000 at best, and many were much smaller. The most significant urban centers were melting pots of diverse cultural influences, made up of peoples of various ethnic backgrounds and many different beliefs.

In general, cities were left to run their own affairs with a fair degree of local autonomy, but they were also required to conform to Roman law and pay their dues to the Roman treasury. Their status was closely tied to the degree to which they possessed imperial privileges. It was also linked to where they were located in strategic terms. The so-called “senatorial” provinces were peaceful enough to be administered by the Senate in Rome via proconsuls or governors drawn from the ranks of former Roman magistrates. A majority of the provinces required an army presence, and much of Rome’s military might was concentrated on the frontiers of the empire, where there were frequent problems from outside forces.

Roman military might was considerable. Across the empire as a whole, around 100,000 legionaries—highly trained forces, volunteers not conscripts, well-equipped, well-paid, and honored for their services—were kept in a position to fight at any one time. The legionaries were supported by as many as 150,000 auxiliary troops, drawn from confederates and subjects, who served as cavalry and light infantry. Colony cities, populated with retired soldiers, were dotted all over the empire as strategic outposts of loyal subjects dedicated to maintaining the Roman way of life in the provinces. The role of the armies in the imperial structure was vital; in the end, they alone could uphold the pax Romana, the Roman peace, upon which all cultural stability depended.

Forces of Unity

For all its vastness, the Roman Empire possessed various unifying forces. Among the most important of these were languages. In a world that embraced Africans, Asians, Europeans, Arabians, and Celts, it was possible to communicate from one side of the empire to the other with a knowledge of only two tongues: Latin and Greek. These were the two official languages of government, law, and commerce throughout the empire—Latin in the western part, Greek in the east, assuming a division roughly along a line running southward from the confluence of the Danube and the Sava rivers across Europe and into Africa. Regional vernaculars and dialects remained standard for most people in the countryside, but the educated members of urban society would learn at least Latin or Greek, and in many cases both, and a knowledge of either of the recognized tongues could carry a person a long way in geographical terms.3

In addition to language, there was law. Rome’s legal system provided, in principle, a common system of rights and responsibilities throughout its dominions. Imperial legislation was a unifying force for all of Rome’s subjects, providing a basis for the evolution of developed conceptions of natural justice. Legal structures were naturally allied to bureaucratic and economic organization. The empire saw an increasingly centralized system of control over regional administration, and various taxes had to be paid to Rome from all parts of the world, especially on agricultural produce, commercial activities, and property transactions. The operation of the legal and fiscal systems was heavily weighted in favor of the educated and the well-to-do, and tax collection in particular was pursued with a rigor that provoked popular resentment and sometimes revolt in the provinces. But however obnoxious its demands, the role of taxation as an integrating force in the imperial order was undeniable.

In terms of cultural influences, art, architecture, literature, and ideas naturally crossed boundaries. Both public and private buildings often reflected generic trends in their style and decoration, and intellectual culture in both Greek and Latin spread through the agencies of a flourishing book trade and the influences of itinerant teachers, rhetoricians, and philosophers. All of these movements were made possible by the empire’s developed systems of communication. The Roman world was crisscrossed by a vast network of roads, the total length of which amounted to around a quarter of a million miles. There was considerable variety in the quality of the road system, but a large proportion of Roman roads were skillfully engineered and constructed, well-maintained, and durable. Their long, straight stretches cut a swathe through all kinds of terrain, using ingenious feats to overcome the difficulties posed by natural phenomena such as marshland or rock. Many of the basic routes chosen by the Romans are still in use today, and the remains of Roman bridges and aqueducts testify to the remarkably advanced character of Roman technical know-how.

Transportation along these roads was very slow by modern standards; progress was limited to the speed of the mules or donkeys employed to pull the various types of carts and carriages in use, and most people were obliged to go on foot. There were perils from roadside bandits, the discomforts of staying in dubious inns, and the costs of various tolls to pay. Nevertheless, for all the problems, travel and trade were more efficient in the Roman world than at any time prior to the nineteenth century.

Sea travel was much swifter than road transport and was a standard means of communication, despite widespread fears about safety. The major shipping lanes had been cleared of the worst threats from pirates in the first century B.C., and they were busy with a constant stream of commercial vessels. There were no special passenger ships, and travelers by sea had to book passage on merchant ships where facilities for passengers were often very basic. Schedules in the modern sense scarcely existed; in general, ships set sail whenever winds were favorable (see Acts 21:1–3). Routes tended to hug coasts wherever possible as vessels moved from port to port to deliver their cargoes. Larger grain ships, such as those plying the vital grain trade between Rome and Alexandria, had to venture onto the open sea, catching the summer winds from the northwest, which would take them from Italy to Egypt in around two weeks. They then had to labor back via a more circuitous route along the coast of Palestine and around Rhodes, Crete, Malta, and Sicily.

Generally there was much less sailing in winter, though ancient literature contains frequent criticism of merchants who were prepared to risk all in pursuit of extra profits off-season, and winter journeys inevitably did take place with fare-paying passengers and important shipments of military personnel. Even in summer the risks could be considerable, because the majority of ships, designed to maximize cargo space, were fairly unwieldy in any sort of rough weather and were furnished with rigging that was ill-equipped to sail in conditions other than a following wind. There were also some lingering dangers from piracy, in spite of the campaigns to reduce this problem.

All forms of travel facilitated the transmission of news, both in person and in writing. Letters were a favorite method of communication among the elite, both for business and the conveying of personal news. They were carried usually by private couriers, acquaintances, or anyone going in the right direction who might be trusted to pass them on. Designated officials had the right to use the Roman imperial post, which used the same dispatch carrier and a variety of means of conveyance to bear important information from person to person across the empire. Nevertheless, the writing and reading of letters or books was confined to a small portion of the population. It is likely that only 10 to 15 percent of the inhabitants of the Roman world were literate, and fewer could write than could read. For the great majority, news traveled by word of mouth, gossiped by merchants, officials, tradespeople, soldiers, and slaves, who carried ideas and stories of current events from place to place as they moved around on their business.

Social Structures

Amid all the outward signs of international unity, the Roman world was in reality a highly stratified and very mixed society. Significant social and cultural snobberies operated with regard to imperial geography, and there were many tensions between the rulers and the ruled. The diverse peoples of the empire could be variously viewed by the Romans as allies or subjects and could in turn regard their ultimate masters as either the guarantors of political stability or the repressors of personal freedom. Degrees of Romanization varied considerably, and there were widespread differences in the degree to which Roman cultural influences were accepted and the ease with which Roman authority operated.

In the social system as a whole, status was primarily determined by ownership of land and property. The elite were drawn from the Roman senatorial class, membership of which was determined by an onerous property qualification. From their ranks came the emperor’s inner council of advisers and the most senior administrators of the empire. Some senators were able to trace their ancestry to the patricians who constituted the traditional nobility of Rome, but the numbers who could do so were declining, and senatorial status was increasingly available to those who won imperial favor, regardless of their family origins.

Below the senatorial order were the knights, or the equestrian class, a much larger group, whose property qualification was less than half that required of senators. Many equestrians, however, became very rich; direct engagement in business and trade was conventionally considered to be beneath the dignity of senators, and this left a lot of the most lucrative commercial opportunities open to knights. From this group many of the military, financial, and administrative posts of the empire were filled.

In local cities there were municipal aristocracies made up of councillors and other officials, who had to be rich enough to pay for public works and the running of civil society at a local level. Beneath all of these were the overwhelming majority of the empire’s inhabitants: first its free persons, who were themselves made up of a variety of classes according to background, ethnicity, means, and opportunities; then the countless numbers of slaves (perhaps a fifth of the overall population) upon whom Rome’s advanced agrarian form of economy critically depended.

There was a vast gulf between those at the top of the social pyramid and those at the bottom, though the position of individuals within the system would become more flexible in later centuries than it was in the first or second century. The ruling elite made up little more than 2 percent of the total population. They controlled the means of economic production, and they typically took a large slice of the economic surplus in order to sustain lives of considerable luxury. Their urban houses were frequently elaborate and well furnished, and they would usually own a country retreat as well. They enjoyed vastly better educational advantages than the majority and possessed a measure of control over the cultural opportunities available to others, not only because of their financial dominance but because they were able to monopolize the services of teachers and scribes. Alongside the privileges went obligations: the elite were obliged to pay significant taxes (though some of these were exacted in turn from their subordinates), finance public-works schemes and entertainments, and provide for the well-being of their extended households.

Compared with those at the opposite end of the spectrum, however, the ruling elite were highly privileged. For a large proportion of the slaves who did almost all the work in the households and large agricultural estates of the rich, there were very few rights other than the provisions of occasional legislation supposed to protect them from particular forms of abuse. In essence, slaves were chattels to be used by their owners as they saw fit. In practice, not all slaves were poor or weak, but their circumstances were closely affected by the status of their masters. Slaves of rich owners had the best chances of a reasonable life and of obtaining their freedom, and servants of powerful people, including the emperor himself, sometimes wielded a good deal of influence in the policies of their household. Those owned by less exalted people had a much worse lot.

Many slaves were able to earn or buy their freedom, and the liberated slave formed an important social type on the lowest rung of the ladder of the free. Many thousands of such individuals existed in first-century society. Some did very well and bettered themselves considerably; though barred from holding magistracies, their sons were capable of progressing as far as equestrian status. In practice, however, a majority lacked the opportunities to advance very far, and many continued to work for their former owners. Whether people were slave or free, there was no welfare provision if they were unable to work on account of illness, old age, or infirmity.

For the great majority, life in the towns and cities was cramped, squalid, and unhygienic. People lived in very overcrowded conditions, generally in small tenement apartments constructed around narrow streets with no sanitation or garbage-disposal systems other than the nearest window. Privacy was minimal, disease was rife, violent crime was common, and the destruction of poorly constructed buildings through fire or natural disasters such as earthquakes was a frequent occurrence. Food shortages were well-known among the general urban populace. The rich and those we might loosely think of as the upper-middle classes may have enjoyed some remarkable luxuries and benefited from the splendid aqueducts, baths, and heating systems for which Roman architecture and technology became famous. But for around 90 percent of the empire’s residents, life was a dangerous, dirty, hand-to-mouth existence. The majority of the wealthy enjoyed a reasonable life span; for the poor, average life-expectancy was well under thirty years.

Imperial law may have been a unifying factor in geographical and cultural terms, but the full safeguards of Roman law were available only to Roman citizens, who had a right of appeal to Rome against the judicial decisions of local authorities and exemption from the most degrading forms of punishment, such as flogging (see Acts 16:37; 22:25–29). Citizenship was traditionally a highly valued prize, reserved for individuals and their families who were deemed to have served Rome well or demonstrated an appropriate degree of “Romanness.” As a means of cementing provincial loyalties, the bestowal of citizenship was to be much used in the empire. In the first century, it was already being extended much more widely, especially under the emperor Claudius (41–54); nevertheless, it remained at this stage a status possessed by only a limited portion of the populace. In time it was necessary to develop new classifications of the legal privileges of citizenship, especially after the early third century, when it was extended to all free people of the empire.

Society at every level was underpinned by an intricate web of patronsubject relationships, the emperor himself being the supreme patron, through whose generosity—so the theory went—...