- 352 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

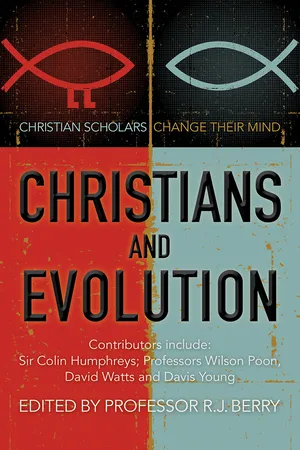

About this book

The debate surrounding creation and evolution divides Christians, particularly evangelicals. It has been a stumbling block for young Christians and a point of contention for the new Atheists. Professor R. J Berry assembles a wide range of distinguished contributors, all convinced, committed and orthodox Christian believers, each of whom has undertaken a conceptual journey, based on sound science and careful theology, from a creationist position to one in which God's creation and the processes of evolution are properly and credibly integrated. Christians and Evolution is a luminous volume that offers a pathway for doubters, sceptics and conservative Christians to embrace the overall scientific consensus of the evolutionary approach, while holding solidly and without reservation to the doctrines of God's creation and God's omnipotence. This text is a must-read for anyone interested in the creation v evolution debate.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Christians and Evolution by R J Berry in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Religion & Science. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Theology & ReligionSubtopic

Religion & ScienceCHAPTER 1

He’s Still Working on Me

Nick Higgs is a postdoctoral fellow at the Marine Institute of Plymouth University. He was born in the Bahamas but came to Britain for his schooling, going on to read Marine Biology at the University of Southampton, and then to study for a PhD at the University of Leeds in collaboration with the Natural History Museum in London. His research is on the ecology of chemosynthetic ecosystems.

He’s still working on me,

To make me what I ought to be.

It took him just a week to make the moon and stars,

The sun and the earth and Jupiter and Mars.

How loving and patient He must be,

He’s still working on me.

To make me what I ought to be.

It took him just a week to make the moon and stars,

The sun and the earth and Jupiter and Mars.

How loving and patient He must be,

He’s still working on me.

Joel Hemphill

I begin with a confession. This story is not about a radical change of heart or mind. At no point in my life could I honestly say that I did not accept the truth of evolution; rather it is about how I came to accept evolutionary theory despite growing up around people who were hostile to the very idea of evolution. I suspect that quite a few people experience exactly the same set of circumstances as I did, and I hope that my story may resonate with them.

Childhood perceptions

My childhood was spent on a tiny tropical island, one of the 700 or so which make up the Bahamas. “My” island was inhabited by around 1,500 other people that made up a close-knit fishing community. Christianity was intricately woven into its fabric. Virtually everyone on the island was a professing Christian, or at least believed in the Christian God – atheists were an alien curiosity. Depending on your particular inclination, you had a choice of Brethren, Southern Baptist or Methodist churches. My parents were active members of the last, and I have many happy memories growing up as part of a loving church family. This church environment, and to some extent that of the other churches on the island, shaped my early attitudes to faith, the Bible, and the world around me.

The Bahamas was a British colony until 1973 (my father was a British citizen) and undertones of British Methodism permeated the church culture. That said, the geographical proximity of the southern United States exerted a strong influence, and determined the flavour of the Christianity with which I grew up. All three denominations were pretty conservative in their teaching (the Methodist church perhaps the least of the three) with a wholly literalist understanding of the Bible and a strong emphasis on personal salvation. The Sunday school curriculum and teaching materials were imported wholesale from the American Bible belt. Evolution would have been seen as irrelevant at best and atheistic or wicked at worst. I have no recollection of evolution ever being discussed in my early childhood years, and later events (described below) suggest that my memory is accurate.

One of the great blessings of growing up in this environment was the hearty singing tradition. I grew up with traditional hymns, and many of the words still spring to mind in different situations. When I was a child, one of my favourite Sunday school songs was “He’s Still Working on Me”. I have no idea why it appealed to me, but it has stayed with me through the years. In many ways it encapsulates the tensions that I later faced when thinking about how evolution related to my faith. The first lines emphasize God’s ongoing work in personally transforming my life while the following lines recall God’s “week” of creation.

As well as a strong Christian upbringing, my childhood home afforded a close relationship with the rest of God’s creation. I spent my early years in the Bahamas immersed in nature, whether chasing lizards, or hunting giant hermit crabs in the bush or watching fish at our dock. Like most men in the community, my father was a fisherman and I spent a lot of time on boats and diving on reefs. I wanted to be a marine biologist for as long as I can remember. This passion was responsible for getting me where I am today. Firstly, it drove my pursuit of a career in the natural sciences, inevitably plunging me into the maelstrom surrounding evolution and the Christian faith. Secondly, it allowed me to fully appreciate evolution when I was introduced to it later on. It seems to me that the better one’s grasp of actual organisms and natural systems the easier it is to comprehend why evolution is such an elegant and powerful theory.

At the age of eight, I had no doubt that God created the world, and this took six literal days. But around the age of ten or twelve I noticed that some things in the Bible didn’t quite add up. I still have my Youth Explorer Bible with carefully handwritten notes in the back pages highlighting discrepancies that I had noticed between the different Gospel accounts of Jesus’ genealogy and also the events of Easter morning in the garden where Jesus was buried. It struck me that in each regard one Gospel must be historically accurate and one not; obviously there was either one angel or two. Perhaps the Bible was not an inerrant factual textbook? Then there was the time when my older brother was told that the Bible was not literally written by God, but by humans inspired by God: “Huh! Well I don’t believe any of that,” he replied. He was being flippant but I remember thinking that there was a point here: humans are fallible. In addition, what I was reading in English seemed to vary depending on which Bible I looked at: I’d certainly never heard of “the prophet Jeremy” before (Matthew 27:9, King James Version)! There seemed to be more uncertainty in the Bible than I had been led to believe.

Of course, I now know that there are numerous possible explanations for the apparent incongruities. At the time though, none of this caused me to give up on studying the Bible or doubt its authority as the Word of God, nor was I disturbed enough to question an adult about these vagaries. Instead, I mulled these ideas over in my mind. I gradually began to understand that the Bible was a complex compendium of documents, each with a historical context. At some point I realized that when it “took him just a week to make the moon and the stars”, it did not need to be taken literally to be meaningful. After all, the persons who wrote the text of Genesis could not have actually witnessed the creation that they describe.

Encountering evolution

At the age of twelve, my life took a different turn. I entered a boarding school in England. The school was located in rural Suffolk, and was surrounded by extensive parkland and woods where we were allowed to play and get our fill of the outdoors. I am thankful for this “right to roam”, which maintained my connection with the natural world, albeit in a very different set of habitats from those of my earlier years. The school had been founded by the Methodist Church, which meant a certain amount of continuity in my Christian upbringing. However, few students were practising Christians. The school was a very different environment for me from both the religious and the social point of view. I had to learn how to talk and think about my faith from a new perspective.

My first encounter with evolution must have come during my GCSE year, when we had a few biology lessons on ecology and evolution. I cannot recall them, but I do remember my sixth form biology teacher instructing anyone who wanted to know more about evolution to read Richard Dawkins’ book The Selfish Gene. The summer following my AS-level exams, I read with fascination and marvel about the intricacies of evolution in that well-crafted book. I was completely ignorant of Dawkins’s views on faith, and I am grateful that I was able to read it without prejudice. I wonder if the same would be possible today, given his high-profile atheism. I am also grateful that my teacher (a devout Quaker) did not hesitate to recommend the book.

It is worth pointing out that at this stage, I had no indication that science and faith might be at odds with each other. I had a solid (albeit immature) grasp of the Christian faith, and I was beginning to understand evolution and other aspects of science in earnest, yet there was no conflict in my mind. I suspect this was because the two strands of my thinking were developing in parallel to each other and failing to intersect.

My first introduction to the science-religion dialogue was a rather obscure one. During my A-level course in philosophy and ethics I had to write an essay and prepare a poster on a significant thinker, chosen from a select list. I opted for the Jesuit priest Pierre Teilhard de Chardin (1881–1955), included for his attempts to synthesize evolution and Christianity. The concept intrigued me – I had not considered the two together. Writing the essay and reading about Teilhard’s work forced me to realize that my science and my faith were not two distinct phenomena but were actually closely linked. Both must be taken together. This monism, that the physical and spiritual aspects of nature are not distinct phenomena, was at the heart of Teilhard’s writings. I was no expert on his philosophy, but I read enough of Teilhard’s works to make a lasting first impression that helped me to understand how science, and evolution in particular, impacted my Christian faith.

There was another aspect of Teilhard that appealed to me: his frequent altercations with church authorities. At this time my adolescent liberalism was bringing me into strong disagreements with authority figures in my churches over issues such as female leadership; I felt a sense of solidarity with anyone who “pushed the envelope”. Teilhard’s thoughts were deemed too radical by the Roman Catholic Church of his time, which led to frequent bans on teaching and publishing his work. This culminated in a 1962 monitum (warning) by the papal office on his work “to protect the minds, particularly of the youth, against the dangers presented by the works of Fr. Teilhard de Chardin and of his followers”. Was this not the same charge levelled at Socrates? Teilhard was as much a hero of free thought to me as Socrates. I admired his self-conviction while at the same time maintaining the humility to submit to his superiors. These episodes in Teilhard’s life also alerted me to the fact that contemporary Christians might possibly have problems with a worldview that held Christianity and evolution together.

Testing the faith

Anti-evolution attitudes became increasingly obvious to me on my visits back home. Although much of my education was taking place in England, my holidays were spent in the Bahamas; indeed, most of my reading was done working on a fishing boat over the summer. On one occasion a fellow fisherman chastised me for reading Carl Zimmer’s excellent book, Evolution: The Triumph of an Idea,1 which he dismissed as “foolishness”. I was not quite ready for confrontation and justified myself on the ground that whether I agreed with it or not I had to at least know about it for my undergraduate course in marine biology. I was more candid with some of my friends, who were shocked and perplexed in equal measure. During a discussion about evolution, the age of the earth, and how it all related to the Bible, one friend said to me, “I’ve always wanted to meet someone who believes in all that stuff.” She went on to question me fiercely, seemingly incredulous as to whether I could actually believe that humans had evolved from a common ancestor with the other great apes. Another friend – my closest friend – thought that my acceptance of scientific orthodoxy was a bit wacky but could see my point and respected my “opinion”. He later told me that one of the Sunday school teachers had considered asking me to teach a class on the topic of evolution, since she knew I was studying science and assumed that I could deliver a defence of literal creationism. She changed her mind, though, when my friend informed her that I was an evolutionist. Perhaps I was a potential danger to the minds of the youth!

It was not only Christians in the Bahamas that seemed hostile towards evolution. A significant contingent of students in the Christian Union at my university in the UK were suspicious of evolution and its perceived atheistic undertones. It was one thing for folk back home to be sceptical, where evolution was fairly irrelevant to daily life, but I was astounded that people studying at degree level (some of them in science) could flatly reject a fundamental tenet of biology. I recall an evening in the pub with men from my local non-denominational church questioning me – “You don’t go along with this evolution idea, do you?” – knowing that I was a science student. I tried to see their point of view. I borrowed a “creationist” book, What is Creation Science?2, from the church library in the Bahamas. Rather than providing a coherent alternative explanation to evolution, it just tried to pick holes using spin and unappealing rhetoric. I was so appalled that I did not return it.

At the same time my science course-mates assumed that all Christians were obtuse anti-evolutionists who were intellectually vacuous. I knew that this was a gross misrepresentation, but I could not deny that some Christians did resemble their caricatures. I began to strongly resent any association with “creationists”, to the degree that I thought I might give up labelling myself a Christian altogether. It came with so much unwanted baggage. Of course, we must all be prepared to accept persecution and ridicule for our faith, but I felt that I was taking flack for beliefs that were not my own. For many of my friends, the anti-intellectualism that they associated with Christianity was a complete barrier to the gospel. I could not talk to them about my faith without the issue coming up. How could I claim to be proclaiming the ultimate truth, while associating myself with Christians who were rejecting the most basic elements of common knowledge?

I found myself contemplating a life outside the church. It seemed that I was being forced to choose between my calling as a scientist and my Christian fellowship. I certainly had no intention of betraying my scientific integrity and could not see the point of being part of a body that could be so wilfully ignorant. I was also frustrated by Christian leaders who seemed to tolerate anti-evolution sentiments in an effort to keep the peace or because they felt ill-equipped. My personal belief in God was unshaken though and I intended to continue as a believer, but was uncertain as to how I could work out my faith. I knew that it was entirely possible to be a Christian without attending church, but I did feel the need for fellowship. Luckily, I found some solace attending a Quaker meeting house from time to time, where the congregants were refreshingly open-minded.

By chance I happened to live in a city with an active branch of Christians in Science (CiS), a network for those interested in the interaction between science and the Christian faith. Some members visited one of our Christian Union meetings to advertise their presence and I jumped at the chance to meet others that might be in my situation. CiS was a Godsend. I began to meet other scientists who were Christians, who took both aspects of their lives seriously. They organized lectures by eminent speakers on various topics in the science and faith arena. All of this gave me a sense of affirmation and reassurance, that that showed me I was not foolish for wanting to maintain my Christian and scientific convictions together. I later attended a short course run by the Faraday Institute for Science and Religion in Cambridge, which opened up my mind to the vast body of research and writings in the science-faith arena. I suddenly felt more confident in my faith and could show people that there were rational Christians out there.

In my new-found zeal, I entered a student essay competition for the Christians in Science magazine. Rather like my previous foray with Teilhard de Chardin, the brief was to write about an inspirational figure in the history of science and faith. After some research, I ended up writing a rather flat bio-sketch of Asa Gray (1810–88), Professor of Botany at Harvard for thirty years from 1842. He was an excellent naturalist and one of the earliest supporters of Darwin in the years after the publication of the Origin of Species. In retrospect, I wish that I had chosen to write about another personal hero of mine: Philip Henry Gosse (1810–88). At the time I didn’t know much about him, except that he was a marine biologist and unshakeable fundamentalist. My distaste for Christian fundamentalism caused me to overlook him for the essay, despite our shared marine interests. While at university I read two publications that changed my mind: the first was Stephen Jay Gould’s essay “Adam’s Navel”3 and the second was a wonderful biography of Gosse by Ann Thwaite.4 Gosse was a passionate zoologist, an effective science communicator, and a correspondent of Darwin. He introduced the concept of the aquarium to Victorian England. Despite his acquaintance and respect for Darwin, Gosse flatly rejected evolution.

Gosse’s story is pertinent to my own, so a slight diversion is in order. He was a biblical literalist and had already spent much time trying to reconcile his science and faith before Darwin published his ideas of natural selection. Gosse subscribed to a Young Earth Creationist interpretation of the Bible, leaving him at odds with fellow scientists, who had shown that the earth was much, much older than the few thousand years that he believed it to be. Gosse reconciled this with a theory that the earth just appeared to be old. He hypothesized that when God created Adam he would have had a navel, even though he was not born of a woman, because it is a part of being human. Likewise, Gosse maintained that when God created the trees they would have necessarily had tree rings, and in the same way the hills would have different rock strata. His whole book Omphalos: An Attempt to Untie the Geological Knot was a litany of examples explaining that signs of antiquity in the natural world were a necessary artefact of a young creation. While seemingly brilliant, it did not catch on and most of the copies were pulped: his fellow scientists found it untestable and irrelevant, while fellow churchmen thought it made God out to be a deceiver. Gosse’s sincere attempt to bring believers and scientists together (as embodied in his own life) was a failure.

Lessons learned

I still admire Gosse because of his steadfast belief that God’s Word in the Bible and His work in creation could not be at odds, since God is the author of both. Any apparent conflict must be a misinterpretation of one or the other. The idea that the one God has written two books – a book of Words (the Bible) and a book of Works (creation) has helped many. The books are written in very different languages but they have the same author; it is nonsensical to think that God would contradict Himself in His books. I suspect that many anti-evolutionists do not know the quotation from Francis Bacon’s Advancement of Learning (1605) whic...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Foreword

- Introduction: In the Beginning God

- 1. He’s Still Working on Me

- 2. Nothing in Biology Makes Sense Except in the Light of Evolution

- 3. From Belief in Creationism to Belief in Evolution

- 4. Connecting Heart and Mind: A Journey Towards Wholeness

- 5. Fossils That Inform

- 6. Learning to Hear God’s Message

- 7. Reflections

- 8. Escaping from Creationism

- 9. Living with Darwin’s Dangerous Idea

- 10. Deluged

- 11. Evolutionary Metanoia

- 12. Deliver Us – From Literalism

- 13. How an Igneous Geologist Came to Terms With Evolution

- 14. What Does Christ Have to Do with Chemistry?

- 15. Discovering Unexpected Dimensions of the Divine Plan

- 16. The Skeleton in the Cupboard: Why I Changed My Mind About Evolution

- 17. Struggling with Origins: A Personal Story

- 18. Changing One’s Mind Over Evolution

- Epilogue

- Going Further