1. Being Rural: An Ecclesiology of the Rural Benefice

Starting with the Incarnation

Just as the liturgical year is given its shape by the celebrations of Easter and Christmas, so this book will reflect the constant dialogue between the Incarnation and the Resurrection that forms our understanding of the nature and person of Christ and therefore heavily influences his Church. It is possible to see parallels between Chapters 1 and 2, which discuss ecclesiology and liturgical theology respectively, and our discussion of Christmas and Easter in Chapters 3 and 4. There is something distinctly incarnational about considering the located church, just as there is something about the primacy and defining nature of the Resurrection which is shot through all our public worship. To push this relationship too far would be a mistake, since of course, just as one cannot divide Christ’s humanity and divinity, to try to hold too much clear water between the Incarnation and the Resurrection would be to tiptoe on the very edge of heresy. Nonetheless, it is true that our first exploration here into what it means to be a rural Christian community is going to draw on a good deal of our theology of place and identity, which has something of the Incarnation about it. Just so, when we begin to think about what the church prays publicly, we will become very conscious of the resurrection trumpets.

‘The Bible makes it abundantly clear that God starts where people are’ (Jones and Martin, p. 17). All ministry is done in context. This might seem to be a statement of the staggeringly obvious, but it is one of the two assertions at the heart of this book. Whenever God interacts with creation, there is a union, a mingling, of the eternal and the transient. The great mystery of the Incarnation, which we retell every Christmas, is the ultimate and perfect expression of this union between God and creation: ‘And the Word became flesh and dwelt among us’ (John 1.14). In Christ we see what perfect union with God looks like. Our ministry of course, although done for love of God, in the name of Christ, and in the power of the Holy Spirit, has to try rather harder to make sense of the mystery of the union between us and God.

We do our praying where we are. For mortal, corporeal humanity that necessarily means our praying is geographical. We must be sitting, standing or kneeling somewhere to pray. Whether in a home, a church building, on the train, on a park bench or in a thousand other contexts, our prayer is located; it is geographical. Not only that, but even in a highly digitized world, a lot of our living is still geographical. Despite the extraordinary revolution in communications in recent decades, exponentially increased by the 2020 coronavirus pandemic, we are still physically somewhere when we connect, by whatever electronic means, with our friends, families and workplaces. Communities exist. Many of those communities became much smaller in March 2020 as the entire nation was locked down. Some communities discovered imaginative ways of re-constituting themselves partially on the World Wide Web or through conferencing software. Some communities struggled desperately with this sort of technology and have felt on the brink of collapse. All communities, I would suggest, felt the pain of the lockdown and that is because the geographical element is still highly significant.

I am not the only priest who has commented on the significant pastoral pain of not being able to shake hands with the congregation at the church door (at the time of writing this is still prohibited under social distancing guidelines). There is something physical, something tangible and grounding, as well as something which is simply deeply instinctive, about human touch. That is connected to the other things about geography: we belong in a place, with a people, and that place and those people matter. They are part of who we are and we are part of who they are.

The purpose of this chapter is to acknowledge the truth of our ‘locatedness’ and to ask how a distinctively rural identity might shape our ecclesiology. In other words, what is it about being a rural Christian community, perhaps a small parish or, more likely, group of parishes, which makes how we ‘do’ our Christianity distinct? When we think about ecclesiology we are thinking about the nature of the church. Some of the things we probably want to say about the church are universal, or perhaps are universal but interpreted and mediated nationally in the case of the Church of England. One of those things is our liturgy and Chapter 2 is all about how we marry authorized national liturgy with context. Other things are much more local. There are things about identity as a diocese, or perhaps as a geographical region such as a county. Some parts of our identity are significantly more local than that and have to do with history, physical geography, patterns of employment, commuting, education and migration.

One of the things it is vital to remember is that God revels in that identity. We know God rejoices and delights in the created order (Prov. 8.31), and what is central to that creation is humanity. It is not a historical accident that the Word became flesh in a particular place at a particular time. There is something about the Incarnation that is all about the experience of an eternal, transcendent, omnipotent, omnipresent God in a particular place, at a particular time, which shows us how it is that God comes close to us.

Building our ecclesiology

As we begin to develop an ecclesiology of the rural church, we need to say some things about God and some things about being rural. There are a number of excellent studies which have done a good deal of this work and I will point to them in the course of what follows. It is a very good thing that there are a number of ways into this question of what rural Christianity might be like, because that means the individual minister, pastoral team or PCC is likely to be able to find a methodology which appeals to them and will help to unpack the issues for discussion. That is really the aim of this book: that the questions I pose here, and the beginnings of the answers that this study moves towards, might inspire people in their own context to have these conversations around the PCC table, or perhaps in small groups, and see where the conversation takes them.

We have to begin with some principles, and those that underpin this chapter are these:

- God is entirely and eternally love, and that does not change.

- We, as human beings, experience God’s eternal love contextually.

Because we hold both to be true, it explains and gives us a mandate to expect that the way in which a community encounters God in a particular context will be, to some extent, specific. This is not because God changes, but rather because humanity is contextual.

We therefore expect that the Church, which is the manifestation of the body of Christ on earth, will also be contextual and might look, feel and do things differently depending on its context. There are a set of eternal and everlasting truths revealed by God through the Church, but those eternal and everlasting truths are transmitted, received and proclaimed by a church that is local as well as universal.

So, what might the principles be in relation to the rural church? I would like to suggest that the following might be a useful starting point:

- Physical geography matters.

- Social geography matters.

- A small church is not the same as a failed large church.

- There are things to learn from the model of cell church.

- There are things to learn from the monastic (or Religious) tradition.

- We need to be confident about our strengths.

- We need to be honest about our weaknesses.

These seven principles will guide the rest of this chapter. Before that, however, there is one other ‘big picture’ aspect which is worth acknowledging.

I wouldn’t start from here!

I remember a visioning exercise that was undertaken in one of the rural contexts in which I have ministered. We began the day by spreading out a large map of the benefice on a table and identifying the various church buildings, the schools, the areas of most substantial population, the main geographical features, the access routes for transport, and so on. One of the repeated comments from those of us in that group was, ‘Well, if I was beginning a Christian community on this patch of the vineyard, I wouldn’t start from here!’ I think it is worth acknowledging that from the outset, because it is a feeling that is encountered by many in rural ministry. Faced with the challenge of a piece of geography within the Church of England, and unlimited money and resources, there would be a strong argument for arranging the buildings, and other facilities, in a very different configuration from that which we have inherited. At least one of us around the table suggested that one large church at the geographical centre point of the area, with a large car park, would be a far more sensible way of organizing Christian ministry in this particular area and there is a good deal of truth in that.

We start, however, from where we are, which is largely with a set of churches built in a period where transport was significantly less easy, affordable and ubiquitous than it is now, when population centres were smaller and there was less regular migration between them, and when the funding of church buildings came from a variety of sources, not least from private landowners.

If we are people of the Incarnation then we know God meets us where we are, and what we have inherited is just as much God’s gift as that which we might develop or create in our own time. It is in that spirit the rest of this chapter unfolds.

1 Physical geography matters

The General Synod report Seeds in Holy Ground, published in 2005, began by confidently drawing the attention of the local church to its context. The first question posed in that rather fine workbook was, ‘Where are we now?’ (GS Misc 803, p. 4). Although the data cited in Seeds are now well out of date, the methodology is sound and repays another reading. PCCs and teams who looked at this report at the time may well find that pulling it out and dusting it off again would be a good starting point. Apart from anything else, the title of the report itself is deeply theological and sets the scene well for all the work that has followed since then.

Seeds refers to ‘the importance of place’ (p. 11), and much of the later writing picks up on this theme. Sally Gaze, writing shortly after Seeds, identifies the deep rhythms and nature of the rural community which lend parish churches in the countryside something of a distinctive identity. She notes that they are:

Naturally drawn to an incarnational approach in that they are inheritors of a tradition that has sought to build on people’s innate spirituality rather than dismiss it as inadequate or superstitious. For example, the celebration of harvest and rogation can be seen as the churches’ attempts to respond incarnationally to the deep awareness of the natural world. (Gaze, p. 10)

Again, the word ‘incarnational’ is used to try to express something of the way in which God and context meet together to form a distinctive experience of the expression of faith.

Honey and Thistles is not primarily an ecclesiological study of rural Christianity, but rather a creative and refreshing approach to looking at farming through the lens of Scripture. It is well worth reading by anyone interested in a rigorously biblical approach to agriculture in the modern age. It does contain within it, however, a couple of real nuggets of ecclesiology. The authors, Jones and Martin, are clear, as am I, that the nature of God doesn’t change from place to place. Nonetheless, a particular context can heighten, or make particularly clear, a universal truth. One of the particular ministries of the rural church is to witness to the whole Church, and to the world, the centrality of the natural world to God’s redeeming purposes:

There are some Christians who see concern with the natural world as a distraction from ‘spiritual matters’. It seems to us that the Bible does not support such a view. There are profound reasons why there are flowers in church and for the celebration of land related festivals such as rogation and harvest. The care of churchyards can also reflect this pattern of relationships. There is potential for thankfulness and joy in these relationships but also, of course, for pain and loss. The natural world does not always cherish us. The Bible does not offer easy explanations for this, but it is completely realistic about the existence of the tough bits. It sees all the relationships as interconnected and mutually sustaining or distorting each other. (Jones and Martin, pp. 110–11)

So, there are some dominant ecclesiological themes in rural communities that flow from the physical environment in which Christian praying happens. They are not exclusive to rural communities and rural communities are not better or worse than suburban or urban contexts because of them. Nonetheless, these ecclesiological themes are present and we do well to recognize and embrace them, because they will help to form us in our praying and in all the witnessing, mission and pastoral care which will flow from that praying. These dominant ecclesiological themes have to do with the natural world, with rhythms and cycles, with creation and with community.

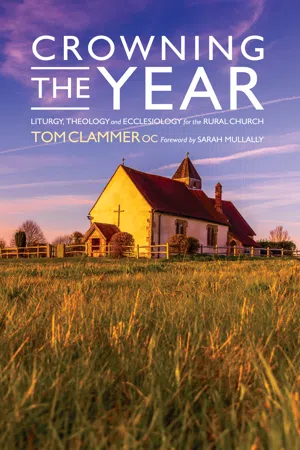

We ought not to move on from considering the physical environment without acknowledging that this includes the fabric of our church buildings. I have sat in too many meetings of the Diocesan Advisory Committee to ever forget the oft repeated mantra: ‘the building will always win.’ Later on, in the chapters looking at the liturgies specifically, we will think more about the use of rural church buildings, but it pays to state at the outset that one of the distinctive things about much of rural ministry in the Church of England is the inheritance of a number of church buildings. As we noted earlier, in the Parish of Tidenham there were four buildings, one of which was closed during the period I worshipped there, and now two more buildings have been added to the cure of souls. In the Severnside Benefice where I was incumbent, we had six buildings, all of which were listed and one of which was Grade I. Going back to that conversation around a map of any set of rural communities, we may not instinctively have started by building four, six, or in some cases dozens of expensive, high-maintenance and often quite large church buildings all over our patch. We may well have opted to build one big, well-insulated and low-maintenance building in the geographical centre, with some really excellent toilet facilities, breakout rooms, catering facilities and a car park. I don’t think anyone would begrudge the rural incumbent or churchwarden that daydream while reclining in a deck chair on holiday somewhere! We are, however, where we are. What we have received are buildings which, as many have commented in previous writings, are often highly visible, prominent and can serve as icons or reminders of holiness. Sometimes, of course, they are in the wrong place, or ugly, or in such a state of dilapidation that they cannot be used. Either way, we have a significant number of buildings to factor into our ecclesiology of rural ministry and that needs to be done carefully, and prophetically. Again, that strong incarnational strand runs through the theology of the rural church. A cluster of dwellings, perhaps a school, gathered around the spire or tower of the country church is an icon of the presence of God in the midst of the people. There is something here of the various characters in the nativity story gathered around the manger. All the outbuildings, animals and fields gathered around the farmhouse. As Jones and Martin put it, ‘the pattern of family and farm under God mirrors this overall pattern of humans, creation and God all in a relationship with each other. It can be a sort of paradigm of the big picture’ (Jones and Martin, p. 111).

2 Social geography matters

If it is vital to take account of the physical terrain when building an ecclesiology of the rural church, it is equally vital to consider the people. I use the term ‘social geography’ to include all the questions around who physically lives in the parish, and where, together with questions of migration or commuting in and out of the parish, the demography of the people, the presence of one or more schools, of local businesses and of agriculture. Vital, also, is where the parishes are located in relation to larger towns and cities, transport links and so on, together with all the spoken and unspoken loyalties and connections that might exist between individuals or g...