eBook - ePub

Tea with Freud

About this book

Tea with Freud is an invitation to go behind the closed door of the psychotherapist's office to get an insider's look at common emotional problems and their treatment. Listen to the verbatim dialogue of actual people in therapy, and learn about an effective approach to resolving their difficulties. Visit with Sigmund Freud himself in turn-of-the-century Vienna, and hear an imaginary but illuminating debate with Freud about what helps people to make changes and recover their psychological health.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1. Where Did the Roses Go?

By the time I reach the apartment building at Berggasse 19, it is nearly two in the afternoon. The sky over Vienna is increasingly cloudy, and the first drops of rain are starting to fall. A young couple walking arm in arm look up at the sky in unison and pick up their pace a bit. Given my destination, it would be fitting to have strident discharges of lightning and thunder, signifying an elemental conflict between earth and sky. Mother Nature is not so inclined today. This is merely a soft spring rain, and I have arrived just in time to avoid getting too wet. I enter by the main door of the building and walk up a long flight of stairs bordered by a wrought iron banister. At the top of the stairs, the door to the apartment suite has his name on it in bold lettering. The door opens, and I am greeted by a maid, a petite young woman who smiles politely but says nothing. I assume that she speaks no English, and I have never studied German. She shyly motions to me to follow her into a waiting room. When we get to a closed set of double doors, she knocks softly and disappears without a word.

“Good afternoon, please come in.” I am not sure what I was expecting, but I am immediately surprised that he is not taller. After all, this is Sigmund Freud. I am standing before one of the intellectual giants of the Western world, and I am not prepared to meet a man of rather average height. He is very handsomely dressed, of course; his three-piece suit is accompanied by a bowtie that is partly hidden, tucked beneath the collar of a clean white shirt. His whole demeanor is professional and confident, but his unremarkable height is not what I have anticipated. I suppose I have traveled to Vienna with some sort of childlike notion of a man who is larger than life, a father figure staring down at me—at all of us—from an Olympian peak. Instead, I find myself eye to eye with Freud, a man no bigger than myself.

“It is an honor to meet you, Professor Freud. Thank you so much for agreeing to speak with me. I know how busy you must be.”

“It is my pleasure.” He is just the age at which I always imagine him. He is neither the forty-year-old with the thick, dark beard and relentless ambition, nor the frail eighty-year-old who is struggling with oral cancer and packing his belongings to escape the Nazis. Someplace in his late fifties, perhaps sixty or so, this is the Freud who has clearly established himself as a major thinker. He is still strong and healthy, and still capable of producing more important work.

I am at least twenty years his junior, still in my thirties; curiously, I feel even younger standing before him. For a brief moment, I glimpse a memory of myself sitting in the library of the Capital District Psychiatric Center in Albany. I can see myself as a psychiatry resident, sitting at a small desk with a volume of Freud’s work open in front of me. There was something in those pages that confirmed for me that my decision to switch from pediatrics into psychiatry was the right move. Freud was trying to go beyond the classification of symptoms and diseases, beyond the typical treatments of his day (water baths, massage, and rest cures), beyond giving the patient suggestions under hypnosis—You can move your arm!—to arrive at an understanding of the root of the problem. He wanted to comprehend the mysteries of the psyche. I remember sitting in that library, paging through his book, feeling like I was being initiated into a very selective secret society whose membership was limited to intrepid explorers of the mind.

Now I am standing before him, and he looks at me directly for a long moment, as if he is already engaged in a psychological calculus of my character. Naturally, I am taking a measure of him as well, trying to read what I can in his eyes. Although he is a man of ordinary height, there is nothing ordinary about his gaze. He looks at me with the eyes of someone with an immense capacity for concentrating on one object at a time, and presently that object is me. There is obvious intelligence in those eyes, of course, and a look of relentless curiosity. Here is a man who can ponder a question for years: What is anxiety? He can wrestle with such a question tirelessly, and he can continually revise his understanding of it. He has a very direct gaze, a look of someone who is neither afraid to see nor afraid to be seen. For a brief moment, I think back and puzzle over something I once read about him. In one of his books, he wrote that he sat to the side of the couch, out of the patient’s view, because he could not stand to have people staring at him all day long. After one long moment of meeting his gaze, I have trouble believing this.

I can imagine that his eyes might be unnerving to some people, but there is warmth in them, too, and it would not be hard to imagine him breaking into laughter and making a joke. I find myself wondering why the photographs of him always show such a stern expression. He is not smiling or laughing at the moment, but there is nothing severe about his gaze. Something in his look makes me feel welcomed as well as analyzed. I wonder for a moment what I convey to my own patients when I look at them sitting across from me in my office back in Albany.

“Come take a seat, and we will have a nice chat. You have traveled far. New York State, yes?” His English is quite good. Accented, but good. My first impression of his consulting room is that it reminds me of a museum, or perhaps the back office of the museum curator—a cigar-smoking curator, to be sure, as the air is permeated with the smell of cigar smoke. The walls are crowded with framed artwork depicting ancient civilizations and their myths. To my left, there is a painting of Pan, the half-man and half-goat of Greek mythology who caused panic in mortals when they encountered him in the forest. In addition to the paintings, there is Freud’s famous collection of miniature antique statues, sitting on a ledge, on a desk, in glass display cases, or wherever there is a bit of space. These are the little artifacts from around the world that he had acquired over time, and there are legions of them. On one table, I see Egyptian figures standing erect, a large camel, and a couple of sitting Buddha figures among rows of other assorted pieces. One would think, judging by the cluttered profusion of antiquities, that the resident of this place is someone who is far more interested in archeology than psychology.

There are bookshelves, of course, filled with hardcover volumes. On one of the shelves, I notice a photo of a woman. She has a penetrating gaze the equal of his. Surrounded by the collections of weighty books and dead little statues, the woman in the photo looks intensely alive and alert. One of his relatives, perhaps? A sister? But he had several sisters, so it would make no sense to have a photo of only one of them.

“Yes, I live in Albany.” The couch is directly in front of me as I enter, and to the left of the couch, there is a wide green upholstered chair for him to sit in while listening to the “associations” of his patients. Why do I keep looking at the couch? In order to answer my own question, I look once more, and then I allow myself the visceral reaction taking shape within me: This is it! I am looking at Sigmund Freud’s couch! This is the couch that has symbolized, for well over a century, a guided journey into the center of the human psyche. This couch was the epicenter of some of the greatest psychological discoveries my profession has ever known. I have to take in every detail of it. There is a large Oriental rug thrown over it, a second rug hanging on the wall behind it, and a third larger one beneath our feet. Of the many colors in the rugs, the reddish browns stand out most to me, giving a very warm feeling to the room. There are large pillows on the couch for the patients to use, as well as a blanket in case of cold drafts in the room. I can barely believe my good fortune at being here.

“Gretchen will bring us tea in a moment. She is a nice young lady, but not very fast.” Freud’s eyes are smiling now. “So tell me, where is Albany?”

“We are due north from New York City. And just straight west of Clark University in Massachusetts, where you lectured.”

“Ah, yes, Clark. I gave five lectures there in 1909. And I lectured in German, with no translator. In those days, serious American students studied German.”

For a moment, I wonder if this is meant as a criticism. I have heard that he does not have a particularly good opinion of Americans in general. His eyes are still kindly, though, as if he is just expressing a reminiscence of his own life rather than a judgment upon mine.

“So you wrote to me about a new approach to psychoanalysis, yes?” he asks.

“Yes, I did. Not exactly psychoanalysis, though. There are still people who identify themselves as psychoanalysts, but I practice a newer model of psychotherapy that is nonetheless based on your original work. It involves a number of changes in both theory and technique, which is why we no longer call it psychoanalysis, even though it follows your most important concepts. Anyway, I thought you might be interested in hearing about it. I have often wondered what you would think of it, and I would love to have your opinion.” These are the words I speak, but as I say them, the word approval drifts into consciousness. Where does that come from? I would love to have your approval. Is that why I really came here today? Am I seeking his approval? I have been practicing psychotherapy for some years now, so why would I care what anyone thinks? Yet there it is: the word approval.

“And I would be very interested to hear about these modern changes,” he says. “Where would you like to begin?” There is a soft knock on the door, and the maid Gretchen enters with a tray. She serves us both tea with sugar from a large serving tray. There are no tea bags, of course, just a pot of hot water with loose tea brewing inside. She places a tea strainer over my cup and pours the tea while the strainer catches the tea leaves. She serves Freud, and then they speak for a minute or two, but I understand nothing except when he tells her Danke. As she leaves the room, I decide I should really study German one day. I wonder if his work would mean something different to me if it traveled to my brain in the rail car of the original German, without changing trains at the station of a translator.

“Please,” he adds with Old World charm and modesty, “educate me about these new ideas, and I will be your humble student.”

“Yes, all right, then. I will begin.” And then I draw a blank. My mind is empty and my tongue is struck dumb. Where should I begin? How did I even presume to come here and tell him about what has transpired since he completed his monumental work? In the psychotherapy approach that I follow, so much of his theory has been rejected or simply discarded, like unnecessary baggage dropped over the side of a ship. I know that my psychoanalytic contemporaries would object, but I find no use for some of his famous concepts. The oral, anal, and phallic stages of development: gone. The central role of the Oedipal conflict in therapy: gone. Penis envy, the libido theory, the death instinct: gone, gone, gone. Even his beloved Interpretation of Dreams has lost some of its importance. But I have to start someplace. I drop a cube of sugar into my cup and stir it around to give myself an extra few seconds to think.

“Well,” I begin, “things have taken a turn that you might not have foreseen. You see, many psychotherapists—I myself am not one of them—left psychoanalytic thinking entirely, after your time was over. Many other types of therapy were developed without psychoanalysis as a basis.”

“Oh yes, I can imagine. There was always resistance to my work, and the struggle is not over yet, I am quite sure.” I can see in his eyes a brief flicker of defiance; there is a readiness to fight.

“Well, some of these other approaches to therapy are not really a resistance to your work; they are just other ways of thinking. And those therapists are definitely helping people. But among those who remained interested in your work—even though we don’t call ourselves psychoanalysts—there has been a kind of revival, along with the development of newer techniques. Actually, part of the newer approach stems from your first psychological publication, the book you wrote with Dr. Breuer.”

“Ah, yes, Breuer. Josef Breuer. He made a very important contribution to psychoanalysis. In fact, he was one of the two greatest influences upon me.”

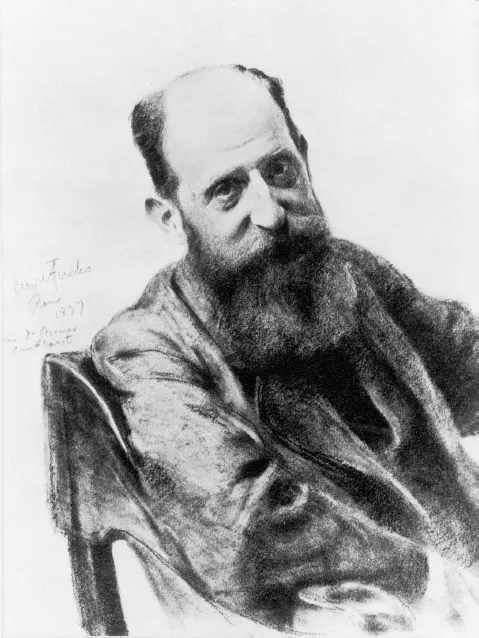

As he offers this praise of Breuer, I get a conflicting message from his body language. The animated defiance that was in his eyes a moment ago is replaced by a look of coldness. He folds his arms across his chest. His lips are pressed tightly together. The overall impression is that he has withdrawn to another room and closed the door behind him. Clearly, I have blundered already. I should have known that mentioning Breuer would be a mistake, based on what I have read about their relationship. Breuer, also a Viennese physician, was a friend, colleague, and mentor to Freud for years. In fact, it was a case of Breuer’s—the case of Anna O.—that influenced Freud to begin the work that would later become psychoanalysis. I remember a photograph of Dr. Breuer in a library book. The camera recorded a man with kindly eyes and a long beard, the perfect image of the grandfather in a children’s storybook, or perhaps the neighborhood rabbi. It is not a face that broadcasts acrimony or ill will, but somehow things fell apart after he and Freud collaborated on a book. The friendship turned to animosity—on Freud’s part—and my mentioning of Breuer has already chilled the atmosphere. I can see that I will be navigating through rocky waters. I remind myself that the unhappy ending with Breuer also happened with others who were close to Freud: his teacher Meynert, his friend Fliess, his disciple Jung. I will have to steer more carefully.

Josef Breuer

“You see, Professor, some of us have emphasized a return to your ideas, even your early ideas published in that book, Studies on Hysteria. We look for negative experiences in childhood that might be responsible for the current symptoms. For example, we look for childhood losses or separations, divorce, child abuse, rejection by a parent, and so on. We encourage the patient to remember those events and situations. And they not only must remember them but also must remember with emotion. They have to get in touch with the buried emotions. As you said in the book, remembering without emotion usually produces no result. So we have gone back to your earliest work, added some newer techniques, and we are seeing wonderful results.” I pause, and there is a long silence. I cannot read his reaction at the moment, although he looks less distant now. Perhaps I have distracted him from my Breuer gaff and got him thinking about his early work. Still, he does not look pleased. I half expect him to end the visit and dismiss me from his consulting room. I take a pre-emptive step by adding one more thought. “We are in the minority of therapists now, but we are convincing more of our colleagues to consider this approach and see its value.” I have read of his struggles with the physicians of his day, and how he often felt isolated and unaccepted by his peers. Maybe I can win him over by getting him to view me and my colleagues as allies who are fighting the same battles that he had fought.

There is only silence. I can hear the ticking of a clock on the wall. At first, I assume that the continuing silence means that he has finished with the discussion. Then I remember that this is Freud, the original analyst, a man who sat quietly to one side of a couch all day listening to people talk. He must have trained himself to listen carefully without interrupting. Besides, I am probably too accustomed to the rapid chatter of my era. Now I am in his world, a slower, more leisurely world. If he could join me in a few of the fast-paced conversations of my typical day, he would probably think we are all quite mad.

“Yes, yes, that was our earliest work,” he finally says. “That was the ‘cathartic method,’ as Breuer called it. We thought that the patient must have an emotional catha...

Table of contents

- Frontcover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- 1. Where Did the Roses Go?

- 2. The Root of the Problem

- 3. Inspired

- 4. The Sight of Blood

- 5. Making the Connection

- 6. An Incompatible Idea

- 7. Beyond Words

- 8. A Hopeless Case

- 9. Prophet and Disciple

- 10. The Last Season of Basketball

- 11. Doubt and Disillusionment

- 12. “Yesterday”

- 13. Writing with Chalk

- 14. Going up in Smoke

- 15. A Fairy Tale Ending

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Tea with Freud by Steven B Sandler in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & History & Theory in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.