![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Context: Where are We and Why are We Here?

How does an industry survive in the twenty-first century when it does not focus on, or even acknowledge value? Generally speaking, the lack of concern about creating value for a customer was overwhelmed and abandoned back in the 1920s, overwhelmed with the advent of advertising to differentiate the multiple brands of a single product, right? That may be true for cars, toasters, and biscuit flour, but up until recently, healthcare has appeared to be immune to the market forces that have demanded that other business segments focus on value.

For most industries, disregarding value while continuing to sustain economic growth is usually short-lived. So why has this scenario persisted for decades in healthcare? There are at least four possible explanations for this phenomenon, either alone or in combination.

The first reason might be the lack of competition in either the product itself or the industry as a whole. In these cases, the product is something that everyone feels they need and there’s only one supplier, or the suppliers are limited compared to the demand. Some examples would be the early days of Texas Instrument calculators or cell phones, or all the (short-lived) days of the Pet Rock.

Another great example would be Ford’s Model T automobile. Price was the driver in this instance, with quality and customer experience taking the rumble seat. Henry Ford is famously quoted as saying, “A person can buy a Model T in any color they want, as long as it’s black.” Ford’s business model at that time was just to churn out as many Model T cars as quickly as possible, make the sale, and keep on building more cars. Ford’s production and distribution models set the standards for mass manufacturing at the time. Eventually, though, people wanted some say in the features and accoutrements of their vehicles. Perhaps corporate healthcare is still in its infancy as an industry.

Competition, or a true lack thereof, in a more mature environment may be another explanation. In many areas, there are few choices for healthcare delivery, especially the acute care services offered by hospitals and facilities. Even between outpatient offices or in communities with multiple acute care health systems, the product being pedaled—namely fee-for-service, transactional, repair shop medicine—is basically the same from one entity to the next. There is talk of brand loyalty with health systems or physician practices, but this “loyalty” is often based on experiences out of the control of the provider (“I won’t go to ABC Hospital, because ‘they killed’ my dad/aunt/sibling/etc.”). Additionally, “brand loyalty” is instantly undermined almost every time by an insurance network if the person has health coverage. If a provider or facility isn’t in one’s coverage network, people generally find another option. More on this when I get to reason number four.

A third reason might be the hubris of the medical profession and healthcare industry. Perhaps we believe that the services we provide are so vital–like public utilities–that people will keep using our services, regardless of our apparent obliviousness to creating value. This notion of indispensability and (this false) sense of invulnerability may have been fueled by the fourth potential explanation…

A disconnect exists in the currency exchange process for services rendered, creating a cushion of ambivalence, or at least opacity, that distracts from the search for value. A customer, by strict definition, is one that purchases a commodity or service. Over 90 percent of the healthcare in the US is paid for by someone other than the patient. Money, in the form of premiums, is deducted from a person’s paycheck (employer), covered by a governmental entity (Medicare or Medicaid), or paid by an individual to a third-party payer (insurer). Generally, this money is held by the payer until a provider or facility submits a bill. The payer writes the check to cover services rendered, and then, after the fact, notifies the patient of the bill and informs them of their portion owed.

. . .

A customer, by strict definition, is one that purchases a commodity or service. Patients are actually customers of healthcare coverage.

. . .

Therefore the payer, whether it’s an employer, insurance company, or the government, is actually the customer in healthcare. While patients are consumers of healthcare services, they are actually customers of healthcare coverage. Once deductibles and out-of-pocket maximums are reached, a patient rarely hands over a significant portion of the bill’s total claim submitted by the provider or facility. Perhaps this distance between the patient’s wallet and the provider’s hands, as well as the distance between provider, customer, and consumer, blurs the typical financial contract between the provider and receiver of services that would normally demand value for the money spent.

From a hospital’s perspective in this disconnected world, insurers and physicians can be seen as patient brokers, each exerting influence over the patient as to where the patient will seek services. Not only is the patient’s choice of where services will be rendered potentially limited, but the patient is also usually not involved in the building of the approved network and is unaware of the actual cost of the services received. This break in the line of financial accountability may have been the greatest contributor to the ignorance of value in healthcare.

Until recently, providers and facilities would regularly raise prices and insurers would in turn raise premiums, but now this is recognized as unsustainable. Sensing the inability to wring any more premium dollars from employers or patients, insurers have begun trying to find ways of controlling costs or shifting more costs to consumers. Again, though, the money spent by the patients tends to be insurance costs rather than directly handing money to doctors or hospitals. Even with a high deductible plan, the patient cost has more of an insurance feel, and if it’s tied to a Healthcare Savings Account, there may be even more of a disconnect between service and payment.

In addition to insurers trying to stretch healthcare dollars in a frenzied inflation of healthcare costs, some atypical, non-insurance company entities have emerged, exerting efforts to bridge the chasm of healthcare funding and payment, and they started to demand value for the healthcare dollars they’re spending. Since employee health care expenses have been the fastest rising costs facing employers over the last few decades, and since many organizations self-fund their own health plans–examples of chasm-bridgers who set aside their own money to pay claims–therefore the concept of Population Health emerged beginning in the early 1990s as an attempt not only to lower costs but to increase value overall. It was in these roots of self-funded employer plans, long before the Affordable Care Act of 2010, that the concepts of Population Health Management to create value were developed and refined.

For some background, let’s examine at a macro level the concept of self-funded employer health plans. An organization decides (or is required) to offer healthcare coverage to its employees as a benefit. Instead of paying premiums to an insurance company for a “fully funded” plan where the insurance company is on the hook for all expenses, the business decides to self-fund a “bucket of money” through its own contributions plus whatever they deduct from the employees’ paychecks, out of which all the medical claims for its employees will be paid. The organization usually hires a Third Party Administrator (TPA) to handle the administrative work of running a health plan, and another company is usually engaged to provide reinsurance, to provide stop-loss protection against large, catastrophic claims.

Given that the organization, the employer, is now on the hook for all healthcare expenses (this is termed “at risk” in the Value-based Care world)–it’s directly their money that has to pay the costs–the company will generally desire to achieve two goals in its administration of the plan:

- They need their employees healthy and at work performing to the best of their abilities. The issues of both absenteeism and presenteeism (gone from work and at work but functioning sub-optimally) need to be addressed.

- They must have the best value for their healthcare dollars. As with any other investment in their business–raw materials, contracted services, marketing, etc. –they must ensure that their investment in healthcare services is yielding the highest quality, lowest cost, and best experience for their employees.

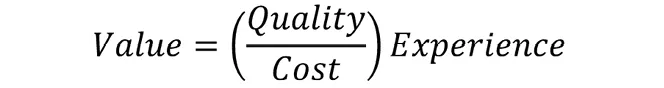

This second need is actually a longhand version of the Value Equation. We will dive deeper into that concept later in the book, but I’ll introduce the construct of value now:

In my work with self-funded employers, I was surprised to learn there were actually two large sub-sets of organizations: those committed to the relationship with and well-being of their employees, and those who merely wanted to check the box of healthcare benefits as cheaply as possible. Why wouldn’t both groups of organizations want what was best for their employees?

Some organizations had a firm grasp of the two issues noted above–keep your employees healthy so they are optimally productive and aim for the highest possible value while funding your healthcare bucket. These companies showed a desire to maintain the longevity of their employees’ employment and engage them in a meaningful and mutually fulfilling...