![]()

CHAPTER 1

Politics

“That’s not a knife…This is a knife.”

(Crocodile Dundee)

‘When politicians offer you something for nothing, or something that sounds

too good to be true, it’s always worth taking a careful second look’.

~ Malcolm Turnbull, Australian Prime Minister, 2015–2018

This word cloud thematically analyses and presents a creative reflection of how we felt about Australian politics over the past decade.

This chapter will reflect on the major political events and key policies throughout the period between 2010–2020 to consider how they may have shaped and influenced our attitudes. It may provide further context as to why we may hold the views that we do today and about trust and confidence with government over the coming decade.

Fourteen years ago, an Australian 18-year-old teenage model from Cronulla in New South Wales was catapulted into the limelight when she broke out with a smile, on a beautiful white sand beach, and uttered six words that went on to create a national, and indeed international uproar. That person was Lara Bingle (now Worthington) and those words were “Where the bloody hell are you?”. This was the tagline to invite visitors to our shores in a reported $180 million advertising campaign by Tourism Australia. The campaign’s objective was to attract visitors from Japan, Germany and the United Kingdom to Australia. Although the campaign reportedly fell well short of those objectives, it became one of our most memorable tourism taglines since “I’ll slip an extra shrimp on the barbie for ya” by Paul Hogan. Banned in the UK amid fierce debate, the ‘Where the bloody hell are you?’ commercial was slammed for its perceived vulgarity. However, while delivering a keynote speech during a visit to Canberra, Tony Blair (former Prime Minister of the United Kingdom) said his first thought on arrival in Australia was “Where the bloody hell am I?”

In December 2019, that tagline resurfaced through a social media frenzy but for a different type of invitation. This time it targeted the Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison in a call to return to Australia from his holidays in Hawaii and lead the country through a bushfire catastrophe of unprecedented global scale and impact. Lara Worthington in a tweet, asked the Prime Minister ‘WHERE THE BLOODY HELL ARE YOU???’ (see Exhibit 1.1)

Ironically, Scott Morrison was the managing director of Tourism Australia in 2006 when the “where the bloody hell are you?” advertising campaign was launched. But getting called out by the woman he made famous, who was originally from his own electorate, the seat of Cook, may well be the ‘karma’ he will never forget.

Over the ensuing months, the tag line remained in the media locally and internationally and was used to call out other ministers, who were absent, hypercritical, evasive or just plain ignorant to the scientific facts on climate change while this catastrophe unfolded around them. The tagline quintessentially captured the sentiment of disappointment in the lack of political leadership among Australians. Climate change is one of the topics where lack of alignment between policy, the espoused position of political leaders and the position of the general populate is most apparent. However, this anger did not surface simply as a response to that single tragic event, but rather reflects the culmination of growing public frustration with political misalignment, inaction, intransigence and shenanigans over the last decade.

Political leadership 2010–2020

‘In politics, if you want loyalty, get a dog.

~ Peter Costello, federal government treasurer 1996–2007

In 2020, Australia closed one of the most politically unstable periods in its history. Our nation was divided, disillusioned and disappointed by the political ‘self-indulgence’ demonstrated by politicians from all political parties and independents included. As unexpectedly spectacular as the end of the decade was politically for Prime Minister Scott Morrison’s leadership (“I’ve always believed in miracles”), so too it was for Kevin Rudd who commenced the decade as Australian Prime Minister, and in his farewell speech after being displaced by Julie Gillard departed with the phrase “we’ve [Therese and Kevin] got to zip”12.

Between ‘zipping’ and ‘miracles’, this past decade saw the prime ministerial leadership change five times within an eight-year period. The electorate became spectators to a democratic system where their best interests took a back seat to factions and political self-interest. The resulting political policy backflips throughout that period were no longer became fodder for opposition parties to challenge, as all parties feasted on them abundantly. It was as if all sides of politics believed they possessed infinite social capital and an endless supply of goodwill. For the electorate this meant that voting for a party or leader espousing particular policy came with less and less assurance that policy would be progressed.

The Australian National University’s (ANU) Australian Election Study13 shows a majority of voters thought the removal of the leader was unjustified. We became sensitised to these leadership spill announcements as both parties delivered more policy uncertainty. That uncertainty has resulted in Australians no longer understanding what each party truly stands for or is committed to. Policies became seasonal features of the electoral cycle, but much less appetising than a good winter navel orange.

More than any other time in our history, this past decade has led to greater disengagement, lower tolerance, less trust and, perhaps, lower expectations of politicians themselves, their policies and the major parties they represent.

‘Faceless Men’

“Valar Dohaeris. All men must serve. Faceless Men most of all.”

~ Jaqen H’ghar, Game of Thrones

In the film series Game of Thrones, the Faceless Men are a group of assassins based in the city of Braavos. They consider themselves to be servants of the ‘many-faced god’ and possess the ability to physically change their faces, shapeshifting such that they appear as an entirely new person. In the series, the Faceless Men only assassinate targets they’ve been contracted to kill.

The term ‘faceless men’ surfaced again in the past decade of the Australian political vernacular to describe those who conspired to bring down the standing prime minister at the beginning of 2010 – Kevin Rudd. Senators David Feeney, Mark Arbib and Don Farrell along with then Victorian MP Bill Shorten, were reported to have initiated the moves that resulted in the replacement of Kevin Rudd by Julia Gillard as Australia’s Prime Minister and leader of the Australian Labor Party. Then Rudd was returned displacing Gillard, but this time Rudd tore apart more than 100 years of Labor Party tradition to remove the power of the faceless men who he felt had knifed him in 2010. Instead, the power to remove and install a new leader would be in the hands of rank-and-file members of the party, making it nearly impossible for a Labor Party leader to be removed. Those changes would likely have stopped Rudd from removing Julia Gillard as leader two weeks prior to these changes and stopped her from ousting him in 2010. Rudd explained “You want to be able to say to the Australian people, you vote for this guy, you vote for this woman, they end up staying on for the duration of the term”14.

But the faceless men were not just a cohort unique to the Labor Party. They reappeared again in 2015 when Tony Abbott, the standing Liberal National Party leader and Prime Minister was brought down by Malcolm Turnbull. Scott Ryan, Wyatt Roy, Mitch Fifield, Mal Brough and Peter Hendy, were reportedly, the faceless men who conspired against Abbott15.

Then came Turnbull’s turn. With members of the Liberal National Party believing Turnbull could not win the next election, the faceless men and women made their move. Peter Dutton challenged Turnbull with support from Mathias Cormann, Mitch Fifield and Michaelia Cash, who delivered the coup de grace by confirming publicly they had abandoned the prime minister. Interestingly, James McGrath, the Queensland senator, who masterminded the campaign to displace Abbott in 2015, emerged from the shadows as the ‘faceless man’ that provided the numbers to displace Turnbull. While Dutton’s challenge for the Liberal party leadership was unsuccessful (40-45 votes), Scott Morrison emerged as the new prime minister. A tweet from former prime minister Julia Gillard, who began the decade of political leadership instability, and subsequently became a victim herself, welcomed the new prime minster Scott Morrison and shared advice for the displaced Malcolm Turnbull on life after politics. Perhaps also, some early advice to Scott Morrison in the event that he too is displaced by faceless men looking to install a new 31st prime minister of Australia (see Exhibit 1.2).

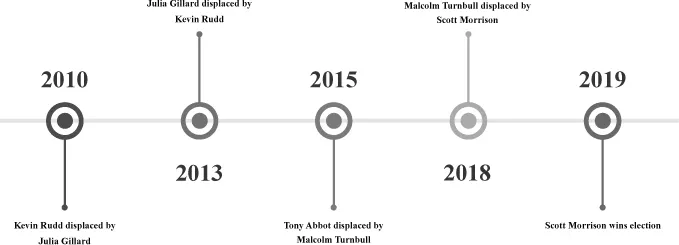

The ‘faceless men and women’ set the scene for an unprecedented decade in our political history where so many prime ministers were removed from power by their own parties. No other country changed leaders more often than Australia did in the eight-year decade— Kevin Rudd (2010), Julia Gillard (2013), Kevin Rudd (2013), Tony Abbott (2015) and Malcolm Turnbull (2018) and Scott Morrison (2018 –) (see Exhibit 1.3).

The prime ministerial office became a revolving door of leaders chosen by their many-headed gods and executed obediently by their faceless men. The subsequent animosity between the anointed and displaced leaders, such as Rudd & Gillard and between Abbott & Turnbull became a public spectre destabilising major Australian political parties, and their policies.

Yet as we commence the new decade, there are no signs that the revolving door of party leadership days is isolated to our past decade. The first sitting day in 2020 for federal parliament, which was to be dedicated to offering condolences to bushfire victims, was instead overshadowed by another Liberal National Party leadership spill. This time in the National Party between Michael McCormack, the standing leader, and Barnaby Joyce, the former leader. McCormack won the spill and consistent with other displaced leaders, Joyce remains on the sidelines throwing stones at his own party.

The past decade showed us just how big the gaps are between factions of major political parties. The manner with whi...