![]()

Why “the Truth” Is Not the Truth

![]()

1

Why “the Truth” Is Not the Truth

I was three or four years old when I struck gold. My dad had been on a business trip to America and had come back with some “koki” marker pens. We never had these in South Africa—or at least no one I knew at play school or our family friends had anything nearly as cool as this.

These pieces of gold were in the shape of a triangular mouse, with a bright-coloured round butt narrowing into a lid with a little white face complete with whiskers and ears. Not only were they cute, but the colours were amazing and not as smudgy as a traditional crayon or chalk.

I was beside myself with excitement, knowing I was going to be the coolest kid at play school the next day. That morning I was up, dressed, and ready to go way earlier than I needed to be, brimming with excitement. Needless to say, the teachers and my friends were all very impressed with this new addition, so at break time I had an idea.

In the playground was an old car that sat on its belly, grass growing within the tyre-less wheel cavities. I sat on the front of it and made each child line up as I proceeded to draw on their faces. I was the chief, and they were all part of my tribe. When I’d finished decorating their faces and had one of them decorate mine, I jumped on the front of the car, looked down at them all, raised my arms high in the air in triumphant victory, and said some stirring speech. Jumping off the car, we burst into fun play, celebrating the occasion.

The bell rang, and laughing and full of energy, we returned to the class at the end of break. Initially, the teachers joined in with our energy and enthusiasm, and then instructed us to all go wash our faces.

But that laughter quickly turned into panic when they realised they were unable to scrub the ink off our faces. The ink was permanent marker. I suddenly found myself in so much trouble, shouted at and sent to the corner of the room to wait out the rest of the day.

The fall from vivacious leader of this giggling tribe to outcast in a matter of minutes was massive. The shame was overwhelming for a three-year-old unable to fully comprehend why the sunshine had turned into a storm. Later, the shame was intensified by the horror of the children’s parents and the scorn of my own as they learnt why I was being suspended from pre-school.

The teacher at play school may have been lovely, but the combination of her handling and my interpretation of the event through the eyes of a three-year-old had such a deep impact on my life. The lesson my little brain learnt was to never claim your space as leader, to stay in the background because it saved you from isolation, loneliness, shame, and rejection. It kept you safe.

As an adult, I look back at that experience and I want to jump into that scene and hold that scared little freckly redhead tight and tell her to never let other people’s reactions stop her from jumping on the car and leading her tribe. I want to explain to her that adults like things neat and tidy, including their little poppets, and that sometimes they can overreact. They aren’t trying to be mean, but in the heat of the moment, they just value order over life’s precious lessons. Sometimes they don’t think deeply about what they’re saying, and their instinctive reaction is to return things back to the comfort of the way they were as quickly as possible.

But even now as I write this response to that little girl with the logic and perspective of the adult, I feel this crushing, burning feeling in the middle of my chest as the shame washes over me. It amazes me how the emotion of that three-year-old’s memory can overpower a far better, more logical adult interpretation of the event.

Journeying with Jess

Becoming a parent has been one of the most humbling journeys I’ve ever been on. My three girls have very different strengths and challenges and, therefore, very different parenting needs. As Jess, my eldest, grows, I get to go back and re-think my experiences of childhood, as in many ways she is very similar to me. She is gentle, kind, and soft-hearted and struggles at school to navigate the meanness of girls—their flip-flopping in friendships or their fights that take others in the group as collateral damage—just as I did.

As she tells me her stories, it’s like she’s retelling my own experiences from thirty years earlier, so I am able to deeply empathise. Yet I have the logic of an adult now to see how faulty my interpretation was at the time and how those assumptions have negatively impacted my journey, stopping me from living my Best Life. I can see the other children’s fickleness for what it is—hurtful words that they don’t mean or that come from a place of their own deep hurt. Those nasty words are intended to elevate themselves in the group as each one jockeys to be accepted by the bully, who is often one of the most broken girls. Many times, these girls have tough home situations and are battling their own demons, looking to fill up their own love bucket with popularity and adoration from the girls and boys in their world.

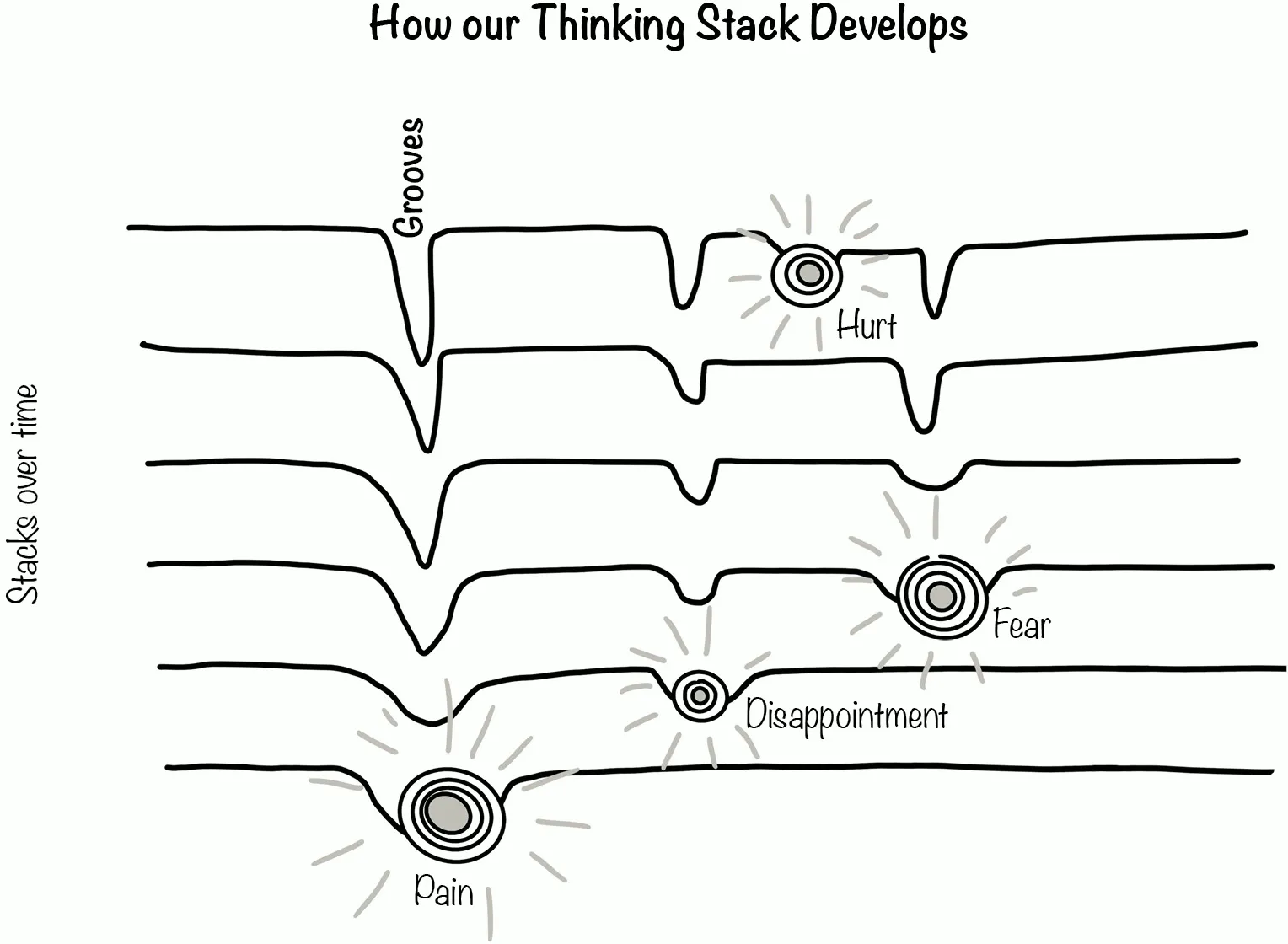

How Our Thinking Stack Develops

Our thoughts over time become our worldview, the framework on which we base all our decisions. These layers of experiences stack sequentially on one another. But without intervention, each experience just layers on the other, with the lumps and bumps of hurtful experiences compacting down over time and forming grooves of behaviour we just slot into automatically, changing our path without us knowing. Like the famous tale of The Princess and The Pea, the pre-school experience becomes the pea in the layers of mattresses, invisible to The World Out There but causing such pain to the princess.

The problem is that as we get older and wiser and our brain develops more complicated processing capabilities, it doesn’t automatically go back and re-process each event. Nor does it apply a weighting scale to reduce the importance of the three-year-old’s interpretation as the thirty-year-old has new experiences. It simply lays down the latest event within the framework it’s developed until that point, regardless of how immature it is.

Our deepest views of our self and our world are formed through the following “Thinking Stack” Framework:

- We experience an event—something we did, saw, read, or witnessed around us that happened in The World Out There or to us and that generated certain emotions.

- We interpret the meaning of that event—based on the age, stage, and brain’s developmental capacity at the time. In addition, we take into consideration the interpretations of the others at the event—our teachers, friends, or parents. We then link that event to others of a similar nature in our past and join dots that may or may not be correct to create cause-and-effect links in order to understand the potential consequences and impact on our safety, security, or status.

- We then form shortcut assumptions that the brain uses to tag and store that event so that at a later stage it can quickly access those shortcuts to warn us of potential harm or draw us to potential opportunity.

- Only later will we be able to see how our brain stored that experience, interpretation, and assumptions as we either (i) think about a new situation and are mindful of our thinking process or (ii) actively reflect on a past event or (iii) act in the moment of a new context.

When we look at that framework, it’s so easy to see how many opportunities there are to develop faulty thinking processes.

As a child we don’t have the emotional skillset to correctly interpret the events we experience. Mean, hurtful children put us down to make themselves feel more powerful. Our interpretations of those events come from other kids too scared to intervene or tired adults just wanting the noise on the playground to disappear, and so our brain forms assumptions based on such flawed thinking. But to us that assumption becomes fact, the truth on which we base all other assumptions to come.

If “The quality of everything we do . . . depends on the quality of the thinking we do first” as Nancy Kline says, then the most important thing we can do is go back and relook at our Thinking Stacks. We can question how true all those messages are that we absorbed from The World Out There and accepted as fact so that the things we do, the life we lead, has a chance of being our Best Life and not one based on the thinking of a young child in a broken world.

![]()

2

Removing the Weeds That Strangle Our Best Life Tree

Our brain is a complex but archaic piece of machinery, phenomenal in its capabilities. Understanding how it works is key to the shortcuts to changing our brain. In its simplest interpretation, it is comprised of three layers:

- The upper, “human” brain responsible for reason, judgement, planning, and self-control that also acts mostly at a conscious level;

- A middle or “mammalian” brain that contains emotions and memory and operates at a subconscious level;

- And lastly, a primitive “reptilian” brain that is responsible for survival, keeping us safe, alive, fed, watered, breathing, and reproducing—all subconsciously.

In the lower subconscious portion of the brain is a part the size of your baby fingertip called the amygdala. Its job is to integrate sensory information, emotional behaviour, and motivation. Many parts of our brain all provide input into this little almond-shaped hub, where it triggers the quickest response to what it perceives “out there.” This is where fear lives, as well as our response to threat—fight, flight, or freeze.

The problem with our lower brain is that so much of its operating system was developed in the days of tribal living, when fitting into the tribe and avoiding lions and other threats ensured you stayed safe, didn’t venture into territory “out there” that belonged to other tribes, and survived. Maslow’s hierarchy of needs of protection and provision are governed right here.

When we mess up, our ancient brain fears that the tribe will kick us out. We want to fight to defend ourselves or flee to hide from the threat. All the voices from The World Out There yell in our ear to pull us back in line with their thinking. For example:

- You see, you should have listened to our definition of happiness.

- You should have stayed in the background.

- You shouldn’t have ventured to the land that the Successful People own. You don’t belong there.

The problem is our world now is very different from the world our amygdala grew up in. It correctly developed through evolution to keep us safe inside the tribe. But now, the world is different. We will not die if we step outside our home suburb or what The World Out There tells us will make us happy. Yes, it seems that most people in the school car park listen to The World Out There and drive fancy expensive cars, and I choose to drive a tiny Honda Jazz. Do I fit in with the tribe? Absolutely not. But will that kill me? No. Does it threaten my basic needs? Nope. Yet my first feeling is one of shame, wanting to fight by justifying to the world why I’m right to not spend huge amounts of money on a car and then wheel-spin out of there, fleeing in shame.

From a brain science perspective, our upper, rational brain is only fully formed when we are twenty-five. This is the part of the brain that governs logic, thinks slowly and rationally, and is able to choose and moderate its response. It can override flight or fight, control our emotions, and keep things in perspective on a good day when it’s energy-fuelled and we’re fundamentally safe.

Until our brain is fully formed at age twenty-five, our primary source of behaviour control is the more primitive brain—the fight, flight, or freeze part, the safe-keeping part that uses and responds to fear and is so vulnerable to others who use fear to keep us within the tribe. It’s why teenagers so desperately need to find a tribe and feel accepted somewhere and can fight an adult as if their lives were at stake. Because for them, they perceive that they are under threat.

Since so much of our identity is formed before we are twenty-five, our concept of who we believe we are is created before we actually have a fully-formed, upper rational brain to logically argue it out with that primitive brain of ours. We had no other choice but to accept as fact that child-like interpretation of the world—to believe what that nasty girl on the playground said about us or the words our tired parents or teachers yelled in a moment of weakness—because we couldn’t talk sense to our broken heart.

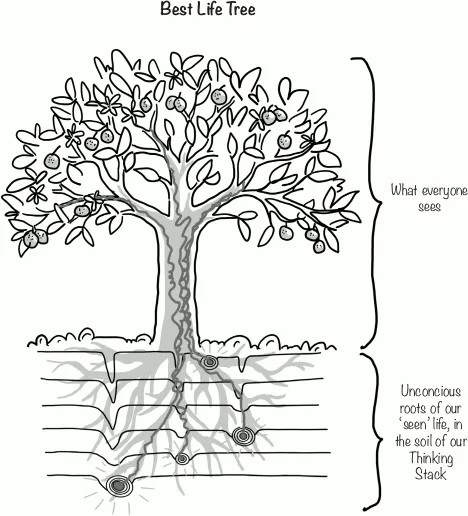

Our Best Life Tree

To understand how your brain functions and impacts your Best Life, think of your Best Life as the biggest most beautiful tree in the middle of a gorgeous, lush garden.

The part you see above the surface is what everyone sees. The success, the fun, the work, the family, the outward health and wealth are all the leaves, flowers, and fruits of the tree.

They’re supported by primary and secondary branches—your relationships; your spiritual, mental, and physical health; the hours you put into your work and managing your money; your learning and personal growth; giving back and engaging in a community.

In biology, this part of the tree above the tree trunk is called the crown—and in our Best Life, we wear a crown of the most beautiful jewels imaginable.

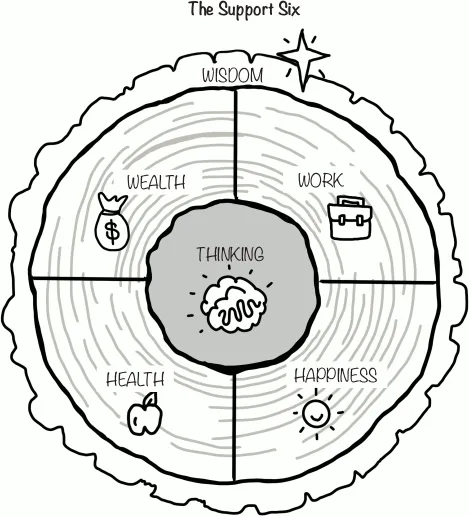

But the crown is only as healthy as the trunk that props it up and feeds and waters those leaves and flowers and fruit. The trunk is made up of the “Support Six,” the essential components to support the beautiful tree of your Best Life. At the core is Thinking—affecting everything you do. Your Thinking is surrounded by Happiness, Health, Wealth, and Work. The outer layer, the bark of the tree, is Wisdom—our guide in this journey of life.

The Thinking core is the strength, the stability, and the food and water of your whole tree. Those thoughts go through from the roots in the soil to the fruit on the trees. Nothing exists without that central core. In the trunk, these thoughts are conscious—we know about them or at least can see their action through the rest of the tree above the ground.

But below the soil line is the subconscious—this huge matrix of deep roots that live below the surface of the ground and the soil. The only wa...