![]()

1

JEOPARDY

Wednesday 7 May 1980. It’s a mild late autumn day in Melbourne but in the inner eastern suburb of Burwood a storm is about to break, one that has been gathering for more than a decade. It arrives at 1.45 p.m., announced by the heavy stride of Frederick Maxwell Bradshaw down the long corridor from the main entrance of Presbyterian Ladies’ College towards the office of the Principal.

Max Bradshaw is a man, in his own conviction, on a mission from God. His critics, whose ranks are about to swell, paint him as a calculating and ruthless zealot. Those close to him revere a devout layman with, as one will say, “a steadfast industry in doing good with the skills which God had given him.”1

A few months shy of his 70th birthday, Bradshaw is thick-set, short of breath and has failing eyesight. Yet he still cuts a formidable figure. He is a leading barrister, a legal text-book writer, a historian and soon to be vice chair of the Scotch College Council. More than this, he is one of the most powerful men in the Presbyterian Church of Australia, and one of its most driven advocates of doctrinal orthodoxy. Appointed the Church’s Procurator, or chief legal officer, in 1959, he drafted the 1953 Act of Parliament which enabled the union of the three congregations of the Free Presbyterian Church of Victoria. That, however, would prove the limit of his appetite for church union.

On this day, on a mission to impose his legal and moral will on the future of one of Australia’s most celebrated girls’ schools, Bradshaw is flanked by the younger, taller and fitter figure of the Very Reverend Ted Pearsons. At 43, Pearsons is Clerk of the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church of Victoria, a position he will hold for a record 32 years. He is also in awe of Bradshaw, his mentor. “I was more like a son to him,” Pearsons would say.2

The two men reach the office, a floor above the school tuck shop, at 1.50pm and are promptly ushered in by the secretary. The Principal, Joan Montgomery, has been awaiting this moment for several years.

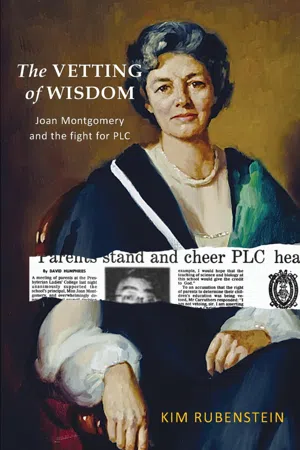

After 11 years as head of PLC, the school she first attended as a student in the 1930s, Joan Mitchell Montgomery enjoys a reputation as one of Australia’s eminent educators. She is president of the Association of Heads of Independent Girls’ Schools of Australia and will drive its merger with the equivalent association of independent headmasters. She is an Officer of the Order of the British Empire and will become a Member of the Order of Australia for her services to education. And, most of all, she is loved and revered by generations of students and parents as an exemplary leader and a warm and compassionate woman.

For the meeting with Bradshaw and Pearsons, Montgomery is joined by her deputies, Evelyn Tindale and Jan Douglas. All three will later file separate notes of the conversation. 3

The formalities of arrival complete, Bradshaw begins with what he calls a proposition for Joan Montgomery but what effectively is a notice of her dismissal: “Given your (employment) agreement has five years to run, we suggest you seek independent legal advice on your agreement with the Trusts Corporation of the Presbyterian Church of Victoria.”

Joan will respond calmly but firmly that her advice is clear: her employment contract transcends the upheaval that has riven the Presbyterian community and stands. But the end of her tenure as PLC Principal and her outstanding career is now only a matter of time.

Six years earlier, on 1 May 1974, the Presbyterian General Assembly had voted to unite with the Methodist Church of Australasia and the Congregational Union of Australia and merge their congregations and assets. The new Uniting Church in Australia, with more than one million adherents, would become the third largest Christian denomination behind the Catholic and Anglican churches and Australia’s largest non-government provider of community and health services.

But not everyone was united. A number of Methodist and Congregational communities would oppose church union and it would cleave the Presbyterian Church in two, with a third of their number resolving to remain as Continuing Presbyterians.

The Presbyterian schism was confirmed when a substantial number of the clergy and laity walked out of the 1 May meeting at the Assembly Hall at 156-160 Collins Street in Melbourne and headed around the corner to reconvene at 46 Russell Street. Among the leaders of the walkout were Max Bradshaw and Ted Pearsons.

These dramatic events would have echoes of the great “Disruption of 1843” which saw the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland split. As Max Bradshaw himself had recounted when addressing the Diocese of Melbourne’s Church of England Historical Society in August 1965: “Four hundred of Scotland’s leading ministers, led by the Moderator of the General Assembly, Professor Welsh, walked out of the General Assembly and constituted themselves the General Assembly of the Free Church of Scotland.”4

Protesting the State’s encroachment on Church independence in appointing ministers to vacant posts, another account by Church historian Alan Rodger records them walking from St. Andrews Church in Edinburgh, “(a)long George Street … down Hanover Street and on to the Tanfield Hall in Canonmills, through crowds mostly waving and cheering but just occasionally hissing. When they arrived at the hall at about a quarter to four, many more ministers and elders were waiting for them.”5

There would be no cheering or hissing crowds when Bradshaw and his brethren marched out of Assembly Hall in Melbourne, but their passion and indignation was equal to that of their Scottish predecessors. Meeting later in Camberwell, the splinter group constituted itself as a Continuing Assembly in defiance of the decision by an overwhelming majority of Presbyterians to unite. Therefore, until the Uniting Church came into being on 22 June 1977, there were effectively two Presbyterian Assemblies.

Bradshaw had been the leading and most effective opponent of church union from the outset. While ultimately unsuccessful in stopping it, he now brought his customary zeal to securing whatever spoils remained for the vanquished. On the day of the decision to unite, the Presbyterian Assembly set up a Property Commission to determine the fate of Church schools—those to remain Presbyterian and those to become the property of the Uniting Church.

Vast power and abiding controversy smouldered in the determinations of the Property Commission, of which Max Bradshaw was an influential member. Upon its deliberations, Ballarat and Clarendon College, The Geelong College, Haileybury College, Hamilton and Alexandra College, Morongo Girls’ College, Penleigh and Essendon Grammar School and St Leonard’s College, all became property of the Uniting Church in Australia.

Manifestly, the weight of numbers went to the Uniting Church with all but two schools going to the Continuing Presbyterians. But those two schools, Presbyterian Ladies’ College and Scotch College, arguably the jewels in the crown, and one of them with singular stature as an educator of young women, were to remain associated with the Presbyterian Church.

Presbyterian Ladies’ College had been founded in 1875 in East Melbourne with an initial enrolment of sixty students. Among the first girls to enrol were Catherine Deakin, sister of later Prime Minister Alfred Deakin and Helen Mitchell who would be one of the world’s most famous women, opera singer Dame Nellie Melba. When the University of Melbourne first opened to women scholars in 1881, many were former students of PLC. They included Constance Ellis, who was the first woman to receive the degree of Doctor of Medicine; Flos Greig, the first woman to be admitted to legal practice in Victoria; Ethel Godfrey, one of the first woman dentists in Victoria; and Vida Goldstein, suffragette and the first woman to stand for election to the Australian Federal Parliament.

Not surprisingly, several court cases attacked the Property Commission—its membership and, moreover, its claim to a wisdom even greater than that of Solomon, with splits affecting thousands of young lives. In 1975, the first two cases centred on Max Bradshaw’s appointment to the Commission. More pointedly, in 1977, the PLC and Scotch school communities challenged the legality of the Property Commission’s pronouncement that PLC and Scotch would remain the property of the Continuing Presbyterians.

While the case was not heard in the courts until 1979, from its initiation onwards rumours abounded around Joan Montgomery’s position as Principal of PLC. But those rumours would not take tangible form until Max Bradshaw and Ted Pearsons came calling in May 1980.

After declaring that Montgomery should seek independent legal advice on the status of her employment contract, Bradshaw pressed on: “We are here representing the Presbyterian Church and while we can’t speak on behalf of the [school] Council it is just as well for you to be prepared for the first meeting where your agreement will be discussed. The existing contracts are not taken over by the new company where they are of a personal nature. Company law prohibits this. Assets and liabilities certainly, but not agreements of a personal nature.”

“My legal advice differs,” Montgomery rejoined, calm by nature and immunised from bluff by Ray Northrop, Federal Court judge and chairman of the former PLC Council. Northrop, steeped in the ramifications of the church split and its impact on PLC, was a stalwart of legal advice and, with his wife Joan Northrop, personal support to Joan. Bolstering his advice was Mallesons, a leading law firm retained by the old Council.

“I believe that all existing contracts and agreements, the Principal and the Staff are to be taken over,” Montgomery noted.

“Not the case,” said Bradshaw, shaking his head, before adding with feigned courtesy, “In view of rumours that you would resign if the Presbyterian Church took over, we thought you would like to be forewarned.”

“I, too, have heard those rumours, among others,” Montgomery countered. “I have never made such a statement and I have no intention of resigning. I appreciate the right of the Council to dismiss me.”

Bradshaw met her head on: “The new Council will have the right not to have the Principal on the premises given the personal nature of the agreement.”

“Quite so,” said Pearsons, in the style of a junior partner but with something of his own to add. “By way of amplification, the Principal plus the staff and groundsmen for that matter are personal agreements and are not covered by Company law.”

Montgomery could see there was little point in carrying on. “This discussion is hypothetical in view of the fact that the first Council has not convened,” she reminded the visitors.

“True,” said Bradshaw, “but from the Presbyterian Church angle it is as well for you to be aware of the situation and prepared, as your agreement will be discussed at the first Council meeting. I am a member of Council, you know.”

With this cudgel he changed tack, acknowledging, “as your contract has some five years to run, the Church would feel bound to make an adequate, indeed a not ungenerous settlement.”

“A golden handshake?” Montgomery replied. “Better than a silver one,” Bradshaw quipped, well amused with himself.

To this point, the Deputy Principals had sat mostly silent but with rising alarm as the threat to their beloved leader crystallised. Ev Tindale, an alert, athletic woman who taught both Physical Education and Modern History, was seldom stunned but this encounter had taken her aback as the threat to the school they all cherished was laid out. Finally, she interjected, “Surely a school’s Principal is an ‘asset’ of the school and is therefore passed over with other ‘assets.’ The personal nature of the agreement is not relevant?”

“Quite relevant,” Bradshaw and Pearsons responded in unison. “There are thousands of cases of precedent where companies are taken over without staff,” Bradshaw added, confidently.

“Imagine what the staff would think if they could hear this conversation,” Montgomery reflected out aloud.

“Oh, no cause for concern,” Bradshaw responded. “Only the Principal is involved.”

But, for all concerned, this was more than a word game or a legal manoeuvre—there were, indeed, several principles involved. And these would play out in one of the most furious battles over a school’s direction and purpose in Australia’s history.

But for now, in Montgomery’s mind, it was time to wind up the meeting. She returned to the point in the circle she had opened earlier: “All of this is hypothetical, there is no point continuing this discussion until such time as Council indicates that my services will no longer be required.”

Bradshaw too was stuck at the beginning. “It is as well to be prepared so a new situation may be met before it arises,” he reiterated.

Appealing for mutual respect, Jan Douglas then spoke what both of her colleagues were thinking. “The ramifications of all this are enormous, far beyond the staff level—what of parents and the education of the girls? The reputation of the whole school is at stake!”

“We are mindful of this,” said Pearsons. But was he mindful of the repercussions of firing a Principal so aligned with the history of the school and so emblematic of its place as a pioneer and bastion of women’s education?

Ev Tindale now spoke again. “As a member of staff and a Vice Principal, if the Council decided not to continue Miss Montgomery’s contract I, for one, would not wish to remain and a large proportion of the staff would think likewise.”

Jan Douglas then further intervened, warning of the fallout with other school stakeholders. “Not only the staff but the parent body of the school would respond,” she added.

“The Council would be aware of these facts and consider them when making their decision,” Bradshaw acknowledged.

And there the conversation came to a halt. There was an exchange of glances, tea was offered and refused, as another appointment pressed, and, with that, the visitors departed at 2.10pm.

……

Wind back to 1939. Joan Montgomery, aged 14 and a student at PLC’s then East Melbourne campus is sitting in the classroom near the clock, off the main corridor that runs from the library to the tuck shop.

As the winte...