![]()

CHAPTER I.

BOYHOOD DAYS

IN the pioneer country of Kentucky, not so very long before that wild, wooded region became a State, began the life of one of our nation’s great men. There, in a remote settlement on Nolin Creek, about fifty miles south of where Louisville now stands, Abraham Lincoln was born. Nothing in his surroundings or his early living conditions foreshadowed the greatness of the man or of his career. Possibly the natural simplicity of his life favored the growth of a great soul. Certainly none of the hampering conditions of luxury, or even of too comfortable living, held it back.

The immediate family into which the hero of our story was born was small, there being only his father, Thomas Lincoln, his mother, Nancy Hanks Lincoln, and a little sister, Sarah, two years old. But there were many bearing the names of Lincoln and of Hanks in the country. Their ancestry ran back to the early beginnings of New England, and the names themselves were ancient English.

With the prosperous and successful branches of the family we have little to do. Abraham Lincoln himself in his later years knew little of them, not even of his grandfather. He said: “I am more concerned to know what his grandson will be.” Knowing, therefore, that among Lincoln’s ancestors there were able and distinguished men, we may pass over their achievements, and begin the story of Abraham Lincoln’s life with a brief account of his father.

Thomas Lincoln was the youngest of a family of five children who were made fatherless by the shot of a stealthy Indian when little Thomas was only ten years old. From that time he was set adrift, “a wandering, laboring boy,” to make his own way in the world. Yet at twenty-five he had bought a farm in Hardin County, Kentucky, and had learned a trade, being called “a good carpenter for those days.” So he could not have been altogether idle and shiftless, though history has usually pictured him so. Besides, he was honest and sober, with strong common sense, and was considered by his neighbors good-natured and obliging; and his love of fun and good stories, traits he handed on, made him unusually good company.

These qualities, even though he lacked thrift and ambition, won him the affection of the devoted woman who became Abraham’s mother. She is described as “sweet-tempered and beautiful… the centre of all the country merrymaking,” and “a famous spinner and housewife.” She was the niece of Joseph Hanks, in whose shop Thomas Lincoln had learned the carpenter’s trade. She was twenty-three years old at the time of her marriage, five years younger than her husband, but superior to him in appearance and in intellect, and in her ability to read and write; for until his wife taught him after their marriage Thomas Lincoln had never learned—possibly because he had been thrown upon the world so young, or perhaps because he had no liking for books. Indeed, few of their friends could boast this accomplishment.

Cabin at Nolin Creek Where Abraham Lincoln Was Born

It was on June 12, 1806, that Thomas Lincoln and Nancy Hanks were married in Elizabethtown, Kentucky. The young couple began their housekeeping in a one-room cabin, fourteen feet square, like many others in Elizabethtown; and there in the following year their first child, Sarah, was born.

As Thomas did not have enough work as a carpenter to supply the growing needs of his family, he removed to the little farm situated on Nolin Creek, which he had bought three years before. Here, on February 12, 1809, Abraham Lincoln was born. Life was already an up-hill struggle for the Lincolns, and they soon became very poor. This was largely because the farm alone did not yield a living, and the father did not get sufficient extra employment at his trade. He would turn off work if it came his way, but he did not go to seek it.

After a losing struggle on the farm at Nolin Creek Thomas Lincoln, when little Abe was four years old, sold out and bought another farm of two hundred and eighty-three acres on Knob Creek, about fifteen miles to the northeast, and removed his family to that place. We may imagine that the journey thither through the leafy woods must have been a delight to the four-year-old boy, who was not old enough to be weighed down by care and disappointment. The song-birds, the flitting squirrels, the flowers, the sunshine, the wind, the trembling leaves and bowing trees, or even the cloud and storm, might well give joy to his sensitive little soul.

They lived on the new farm only three years, little Abe being seven years old when they moved away; but after he had grown to manhood, Lincoln could recall incidents of his life at Knob Creek. Here a baby sister was born and died. Here the little fellow began manfully to share the family work, fetching and carrying for his father, picking berries, even helping to plant seed.

But the family fortunes did not pick up; and as a dispute arose about the deed of his farm, Thomas Lincoln once more decided to sell out and seek a new home.

Most of the good land in Kentucky was being rapidly settled, and a good farm there would have cost more than he was able to pay. Moreover, a brother had prospered in Indiana, and other relatives had gone there. Then, too, as his son said later, he wished to go where there were fewer slaveholders. So this time Thomas Lincoln decided to leave Kentucky and cross into Indiana.

Of the first seven years of Abraham Lincoln’s life we know almost nothing. His only playmate was his sister, Sarah, for neighbors were not close enough to see much of each other. He must have played much alone in the forest and about the streams, making friends with the world of out-of-doors. He was seldom known to speak of those early years even to his best friends, but when someone asked him later in his life if he remembered anything about the War of 1812, he told the following story: “I had been fishing one day and caught a little fish, which I was taking home. I met a soldier in the road, and, having always been told at home that we must be good to the soldiers, I gave him my fish.” This shows us that as a child he was generous, and that he had been taught to be patriotic. Another of his memories was of his mother taking himself and Sarah to say good-by to the grave of his little sister before going far away to their new home in Indiana.

Thomas Lincoln sold his claim to the farm in Kentucky for twenty dollars and four hundred gallons of whiskey. Whiskey to us seems a strange kind of currency; but it was far less bulky than the corn from which it was made, and as trading was mostly by barter, or exchange, it often passed from one owner to another in the process of buying and selling.

With the proceeds of his sale and his kit of tools, he boarded a rude raft of his own making and drifted down the creek to the Ohio River, landing some miles below on the farther shore. Here he made acquaintance with a settler by the name of Posey, and leaving his whiskey and kit of tools with him, pushed inland through the dense forests in search of a suitable spot for his new home. On the first day he selected a place near Little Pigeon Creek, eighteen miles north of the river, and one and one-half miles from Gentryville. Then he walked back to Knob Creek for his family. Again the simple preparations to move were made, and the life in Kentucky came to an end.

Two borrowed horses carried their household goods, which consisted of a little bedding and clothing and also a few cooking utensils. The children were tied to the load upon the horses’ backs. The father and mother walked, the father carrying his rifle to protect the family and provide necessary food. He carried his axe also, that constant companion of the pioneer, not only in the woods for chopping a way through, but at the journey’s end for making the home and its rude furniture.

On reaching the Ohio River the horses were set free and headed homeward. A boat carried the Lincolns across the river, and on the other side a wagon was hired from Posey. Then Thomas Lincoln with his family started on their journey northward. As he had to cut a road through the forest, they were three days on the way.

The four were entirely alone. They had not even a domestic animal—a cat or a dog—with them. The journey must have been a dreary one, for it was the last of November and the weather was more or less wintry. They had no shelter at night except the leafless trees, nor any protection from the cold except the clothing they wore and the brush fires around which they slept under the open sky. Yet the two children probably had much pleasure out of the changing experience.

Having arrived safely at the end of their journey, all set to work with a will to provide a shelter against the winter. Young Abe, though only seven, was healthy, rugged, and active, and all day long he worked with his axe, clearing away the bushes and thick underbush, while his father cut down saplings and made poles for their “camp.”

This “camp,” in which they must live until they could build a good cabin, was a mere shed, fourteen feet square, with one side open. The poles were laid one upon the other, and were topped by a thatched roof of boughs and leaves. As there was no chimney there could be no fire inside, and it was necessary to keep one burning all the time just in front of the “camp.”

Lincoln Helping His Father Make “Camp”

During this first winter in the wild woods of Indiana the little boy must have lived a very busy life. Besides the building of the cabin, which was to take the place of the “camp,” a clearing had to be made for the corn-planting of the coming spring.

A whole year passed before the Lincoln family moved into the newly built log cabin, giving up the “camp” to some friends, Mr. and Mrs. Sparrow, who had followed them from Kentucky. With the Sparrows lived Dennis Hanks, a young cousin of Mrs. Lincoln.

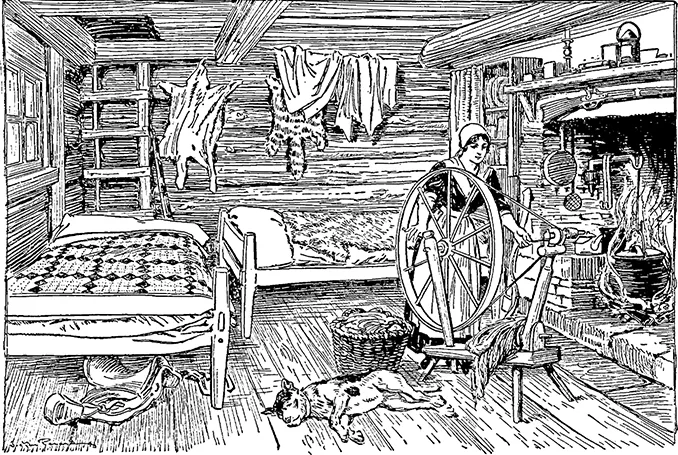

The new cabin had no windows and no floor except the bare earth. There was an opening on one side which was used as a doorway; but there was no door, nor was there so much as a deerskin to keep out the rain or the snow, or to give protection from the cold wind.

In this rough abode the furniture was scanty and of the rudest sort. The chairs were only three-legged stools, made by smoothing the flat side of a split log and putting sticks into holes bored underneath. The table was of the same simple kind, with four legs instead of three. The rude bedsteads in the corners of the cabin were made by sticking two poles into the logs at right angles to the walls, the outside corner, where the poles met, being supported by a crotched stick driven into the ground. Then boards were placed across the poles, making a framework upon which shucks and leaves were heaped, and over all were laid the skins of wild animals.

Abe’s bed was a pile of dried leaves in a corner of the loft, and he reached it by climbing on pegs driven into the wall. In winter the cold winds whistled about his head, the snow sifted in through cracks, and even the drip of rain fell on his face.

A Pioneer’s Home

The food was simple, but there usually was plenty of it. The Lincolns raised enough corn to supply the household, the meal being made into “corn dodgers,” roasted in the ashes, which was their every-day bread. Wheat was so hard to raise and so scarce that flour bread was reserved for Sunday mornings. The principal vegetable was the common white potato, and sometimes that was all the Lincolns had to eat. We get a flash of Abraham’s humor and learn something of his father’s religious habits from Abraham’s remark to his father, who had just asked a blessing on a dish of roasted potatoes, that “they were mighty poor blessings.” But, as a rule, there was an abundance of game, such as deer, bears, wild turkeys, ducks, and pheasants, many kinds of fish from the streams close by, and in summer wild fruits from the woods. These were so plentiful that they were dried for winter use.

It was easy to get game, for not far from the Lincoln cabin was a glade in which there were deer-licks. Waiting here one or two hours usually resulted in getting a shot at a deer, which would furnish food for a week, and also material for moccasins or shoes and breeches. But the cooking was rudely done, because there were few groceries and few cooking utensils. A simple but most useful article in every pioneer household was the gritter. It was a piece of flattened tin punched full of holes and nailed to a board. Many articles of food could be grated on it, and at times the housewife secured by this slow method enough corn-meal for bread.

Method of Grinding Corn

When washing-day came, the clothes were taken down either to the flowing stream or to the watering-trough, which at that time was the closest approach to our modern set tubs. Indeed the backwoodsmen had to devise many contrivances to supply their lack of manufactured things. Thorns, for instance, were used for pins, bits of stone for buttons, while for a looking-glass a woman would scour a tin pan. As there was almost no money in circulation, people exchanged, or “bartered,” for things they wished, one man paying maple-sugar for a marriage license, and another giving wolf-scalps! Candles were a luxury much of the time, and Abe, as we shall find later, spent many long winter evenings reading by the light of blazing logs in the rude fireplace.

These were busy days for Abraham. As a small boy he did the numberless chores which come around with surprising frequency to the boy who lives on a farm. He also cut brush, chopped fire-wood, picked berries, and helped plough and plant. Although in his brief biography, written in the third person, he said that he did little hunting, he told the following story about his shooting a wild turkey:

“A few days before the completion of his eighth year, in the absence of his father, a flock of wild turkeys approached the new log cabin; and Abraham with a rifle-gun, standing inside, shot through a crack and killed one of them. He has never since pulled the trigger on any larger game.”

While the boy kept busy with tasks about the farm and helping his father in the carpenter-shop, the simple, active life was making his body strong and wiry, and his muscles firm and hard.

As he grew he became a tall, slim, awkward boy, with very long legs and arms. His dress, like that of all pioneers, was picturesque and somewhat peculiar. He wore trousers and moccasins made of deerskin, and a shirt, which was often of homespun linsey-woolsey, but sometimes of deerskin. In winter his cap was of coonskin, while in summer he wore a rough, unshaped straw hat without a band. Probably this costume was very comfortable and well suited to the pioneer’s life; but we are told that Abe’s deerskin trousers, after getting wet, shrank until they became several inches too short for his long, lean legs. Then his jesting companions called him “long-shanks.”

But the privations of these “pinching times,” as Lincoln later called them, were as nothing compared to the grievous loss of his mother. The rough life of the forest and the exposure of the open cabin had weakened her naturally frail constitution. Besides, there was much malaria, and in 1818 a frightful pestilence, called “milk sickness,” swept away a large part of the people in the little community near Pigeon Creek. Among those who died were Mr. and Mrs. Sparrow, who had occupied the “camp,” and Abraham’s mother.

She was the nine-year-old lad’s dearest friend. They were knit together by common traits that held them in closest sympathy and understanding. They had the same alertness of mind, the same sensitive feeling, and the same strain of sadness tingeing their natures. Before her death, in her final parting, she said to the boy sobbing at her bedside in his first great grief: “Abraham, I am going away from you, and you will never see me again. I know that you will always be good and kind to your sister and father. Try to live as I have taught you, and to love your Heavenly Father.”

There was a long interval after her death and burial before a preacher came near enough this remote settlement for a funeral service to be held. But before a year had passed, it is said, the young boy sent a message to a Baptist preacher who had more than once been a guest of the Lincolns in their Kentucky home, and persuaded that good man to come more than a hundred miles to hold a service at his mother’s grave. The oft-quoted remark, “All that I am or ever hope to be,...