![]()

THE EARLY YEARS

The Europeans had the technology to build steamboats for almost a century and did nothing with it. The reason was they didn’t have a need for them. Europe and England had plenty of good roads and harbors to handle their shipping needs. This old established transportation system had worked well for hundreds of years so why would anyone in their right mind want to change it. So this first mechanical transportation system would remain an ongoing science project that many would tinker with from time to time.

On the other side of the Atlantic things were different. America was a young nation that lacked roads or the money to build them. This new country was blessed with a natural system of inland rivers and lakes that were ready for use if only they had a quick way of moving people and goods on these water arteries. America was going to have a difficult time developing as a nation if it couldn’t find a new technology that would help it push inland into its western territory on these waterways. Here then is the story of how the experimental steamboats and canals produced by English and French engineers were fashioned into a practical working transportation system by Robert Fulton on this side of the Atlantic.

Going Nowhere

The newly formed United States of America was bursting at the seams with her teaming millions all located within a few miles of the Atlantic Seaboard. The barriers that stood in her way were a mixture of politics and geography. Spanish ownership of Florida and the great Louisiana Territory blocked expansion to the south and to the lands west of the Mississippi River. Mother Nature, not to be out done, had placed the Appalachian Mountains as a great wall running through Georgia, North Carolina, Virginia, Maryland and Pennsylvania. Only one small crack in this mighty fortification known as the Cumberland Gap afforded enough room for small wagon trains to make the trek west, weather permitting. To compound this problem further the nation’s major waterways like the Atlantic Seaboard, Hudson, Delaware and Susquehanna rivers ran north and south. The only practical route around these obstacles to the Western Territory of the Ohio Valley lay across New York State. Millions of acres of cheap federal land were awaiting pioneer families that were brave enough to make their way to the nation’s Western Promised Land by this northern route.

Today most New Yorkers think of St. Louis, Missouri as the gateway to the west. Back in the 1790’s the trek west started at the doorstep of Albany, NY. Thousands of pioneers would embark on their journey west by sailing up the Hudson River to Albany. After getting outfitted with provisions and a good wagon they joined a train. The path they followed went through the old Indian lands of the Mohawks, Oneidas, Tuscarorans, Onondagas, Cayuga and Seneca nations, as they made their way west to the shore of Lake Erie. It was here that they built rafts and completed the journey using nature’s water highways. Down lakes they went turning into rivers and finally arriving in a valley or on a plane where they established a homestead. For every family that made it there were others that died in the untamed waters as the wreckage of their dreams floated ashore.

One thing that all of these early settlers faced were the lack of a good reliable transportation system to service their needs. As the lands between Albany and Lake Erie were bought up and the Ohio Valley filled up all of these new settlements cried out for a way to get their farm goods to markets in the east. If you had no one to sell your croups to you could lose your farm. The further west you lived the greater the problem was as farmers lost their homesteads for nonpayment of taxes or mortgage foreclosures. For many years these first settlers lived in a forest bound wilderness, cut off from the rest of the world.

With all of these difficulties to overcome why would anyone in their right mind want to move west? The simple answer to question was opportunity and ownership. If you could become the first blacksmith, store or public house owner in a new frontier town your opportunities to grow and prosper were almost unlimited. Western undeveloped land that houses, business and farms could be established on went for pennies on the dollar compared with what land sold for back east. The difference between boom and bust for these early pioneers was transportation to and from the great markets of the east.

The first attempts to remedy this situation started off with small armies of ax men trying to widen well-worn wilderness trails. This proved to be a slow expensive process. The Williamson Road was one of these glorified paths that inched its way from Pennsylvania to Col. Rochester’s small settlement on Lake Ontario throughout the 1790’s. The other well-trampled path was the one running from Albany to Canandaigua, which served as the unofficial capital of western New York.

The water routes used by the early settlers for shipping involved the daring use of small rivers like the Canisteo and Cohocton. In the early spring or late fall every year they briefly had enough water in them to float rafts of lumber and food down to the great Susquehanna River. From there they made the long journey south down to Baltimore, Maryland. Many an early settler was lost to this watery graveyard of raging waters or was robbed on the long walk back home. What solved this dilemma was a great deal of European science and American spunk.

Fulton’s Vision

The mighty Hudson River was a super highway of commerce with hundreds of sailboats and slow moving barges navigating her waters. Travel up the Hudson was an uphill battle run against a strong southern flowing current. The sailboat trip to Albany that took three days was swift compared with the seven day bumpy ride by stagecoach or the two week trek on foot. All of this would be forever changed by Robert Fulton’s return to America with two English steam engines.

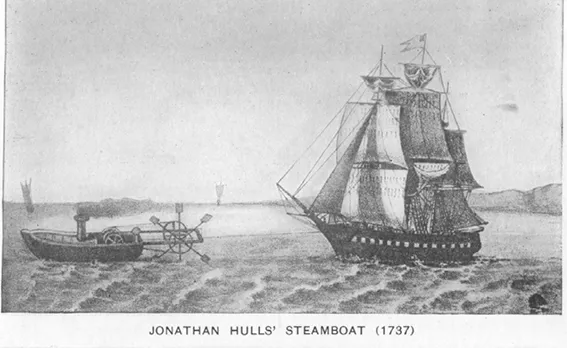

From an early age Robert Fulton had displayed a talent for art and anything mechanical in nature. With the end of the Revolutionary War, Fulton finally had the opportunity of going to England to pursue a career in art. While there he discovered that an artist by day could be a well-paid draftsman by night. Britain at this time was a hot bed of new technologies being produced by its Industrial Revolution. This involved new ways of mining deep in the earth for coal and tin. By using the abundants of coal mass production of cheap goods could be made of durable iron. And to keep the mines dry large steam powered pumps had been developed. The steam engines developed for this task were the most advanced ones in the world at that time. So impressive were these power plants that inventers like Jonathan Hull drew up patents that show them being used on boats and other forms of transportation.

Fulton’s would-be career as an artist went from making paintings of ladies in small lockets that their suitors carried with them to that of a draftsman making illustrations of machines and canal equipment. It was around this time that he started writing papers about the advantages gained by building canal systems.1 He was also learning everything he could about the efficient Watt’s steam engines being produced by the firm of Boulton & Watt. Writing them letters as well as visiting their plant.2 He also had many friends who were canal builders that he helped by inventing new ways of moving barges on these man-made rivers of commerce. In time he was convinced that a canal system like the one being built England could one day help solve many of the problems back home. If America could be united with a canal system connecting the major lakes and rivers into a national transportation system with boats powered by steam as shown in the Jonathan Hall paten of 1737 marvelous things could happen in America. The steam engine by this time had dropped in weight to the point that it might one day be mounted on a well-built boat.

In 1802 Fulton moved to France and became a good friend of the U. S. Minister to France, Robert R. Livingston. Fulton and Livingston were almost like a father and son who were both passionately intrigued by the same things. The subject of steam power being applied to inland shipping was at the top of their list. All of those borrowed ideas they had been collecting from English and French engineers over the years were finally put together in a steamboat they built on the Seine River. After some major problems with the local shippers were solved and a few mechanical ones were ironed out their steamboat finally left her pier traveling at a humble four miles an hour. Their steamboat of 1803 was by no means the first such craft ever built, but it did act as a working model for what they wanted to bring to America’s waterways. One thing they both agree on was that a really successful boat needed the more powerful and reliable Watt steam engine. At this time England didn’t allow for the export of their highly prized technical master piece.

Fulton’s experiments brought him to the attention of the French Government who were extremely interested in his papers about underwater navigation in a boat he called a submarine. Before long he was building submarine mines and a real working submarine that he called the Nautilus with French grants. Napoleon Bonaparte, leader of France had a difficult time believing in Fulton’s inventiveness and kept putting off making a final commitment to fleets of steamboats and submarines. By the time he awoke to how brilliant it would be to sink England’s Navy with submarines and move his arm across the English Channel on a windless day with a fleet of steamboats Fulton was back in England.

It seems that while Napoleon was at a lost as to what to do, Fulton had grown tired of this game having broken up all of these inventions and selling the metal to a scrap dealer to raise money for his passage back to England. Now all of that wonderful technology paid for by the French would become the property of the Royal Navy as Fulton was paid for his knowledge. As part of the deal he was given the right to export two Watt steam engines to New York City where he and his partner Robert R. Livingston had agreed on as the place to build their steamboat at. So in 1806 Robert Fulton sailed home with a head full of knowledge and two of the finest steam engines in the world.

Fulton’s Folly

Almost twenty years before Fulton started building his steamboat a native born American genius John Fitch had built and operated a steamboat out of Philadelphia on the Delaware River. After years of failures, experimenting, engine and boat building Fitch finally produced a steamboat that cruised up and down the Delaware at a speed of over eight miles an hour.

The Congress of the United States was meeting at Philadelphia that year. Congressmen were seen watching Fitch and his steamboat do things that were impossible for sailing vessels to do and yet they never gave any government backing that was so badly needed at the time. The local owners of sailing craft spread stories of what would happen if the boiler bust and how sparks from the boat would set the waterfront on fire. As a result of these stories and lack of government backing no one was willing to ship cargo on her and would be passenger used sailboats. When the money to operate the steamboat ran out Fitch was ruined and the boat was scrapped.

Now it was up to Fulton and Livingston to make steamboat travel a reality on America’s waterways. By this time the prog...