We saw their children play in our streets… . They have vanished but their presence cannot be unseen.

–Jacob Cramer, Provincial Governor

A small town near Westerbork

Emmen is a small town in Drenthe, the least urbanized province of the Netherlands. In this northeastern border area, the earliest inhabitants are said to have lived, thanks to the many surviving prehistoric megaliths, but the area was not included in the Dutch Republic that fought the Eighty Years’ War against the rule of Habsburg Spain, the real founding moment of the nation. The swampy territory interspersed with spots of sand and some habitation only became a fully-fledged province in the nineteenth century. Sheep were introduced to enable arable farming on the poor soils, which generated the expansion of large tracts of heathland. The population increased when the extraction of peat as fuel took on great proportions. Poor families were attracted to the labor in the peatlands, usually moving from one field to the next. They had to dig the canals and then cut the peat, the accumulated residue of Ice Age plants, into straight blocks. As the last peatland still in operation, many families settled near Emmen in the twentieth century. Another influx of residents came about through initiatives by charities to transfer the ‘socially maladaptive’ at a distance from Holland’s thriving cities.

This history provided the backdrop for designating Drenthe as a suitable location for a refugee camp after the German and Austrian pogroms of 1938. Situated on a deserted plain, 25 kilometers from Emmen, the camp remained hidden from view of the civilian population. ‘Our shoes sink into the mud and mold. May we be so indecent and request for wellies?,’ one of the first refugees wrote to his Dutch friend who eventually was incarcerated in the same camp after the German occupation of the Netherlands.1 By then the camp had been transformed into a Durchgangslager from which more than 100,000 detainees were sent from 1942 to Auschwitz and other sites of annihilation. In that same year, 180 Jewish residents from Emmen had been gathered one evening by the local police and sent to Westerbork. In August 1944, Anne Frank arrived at the camp after being arrested along with her seven fellow residents from the secret annex. After one month, the eight unfortunates were deported to Auschwitz. With the exception of Mr. Frank, they all perished in different camps in Europe.

Even before the war, the population of Emmen had increased in number and the village had grown in size. After the war, local and central elites joined forces to provide for the corresponding infrastructure and urban ambience. Actually, they did a lot more. A civilizing mission was launched to turn Emmen into a splendid showcase of modernist upgrading. In ten years, industry was lured to the region to compensate for the declining peat industry while urban planners reinvented the town plan by designing residential apartments in geometric shapes, schools and a shopping mall situated in a green scenery. Not only did public space have to modernize, peat workers had to become town dwellers, and that transition required a new and modern attitude to life, education and taste. First subsidized culture was brought to the former peat villages to prevent cultural lag, as the expected discrepancy between rapid technological change and slow cultural adaptation was called. Then the families themselves had to move to Emmen and transform into the workers of the town’s new textile and synthetic fiber industry.

The transformation of Emmen was spectacular, but similar developments could be witnessed in other parts of the country. In the 1950s, the early years of reconstruction were over. Germany had reestablished itself in Europe and the border with the Netherlands was reopened. The debris had been cleared, the prosecution of Nazis largely halted. After the debacle of the decolonization war in the late 1940s, the Dutch turned their eyes to the future. A modernization offensive, the foundations of which had already been laid before the war, could be accelerated partly, thanks to overseas financial aid. Europe arose in a process of Americanization. How did this forward-looking period of reconstruction and modernization relate to the traumatic past of mass violence?

In the Netherlands, a series of remembrance practices had been set up around the central belief that for five years the country had been the victim of the greatest possible oppression but that, thanks to the perseverance of the people, of which some had taken a particularly heroic stance, the nation could look back with heads held high. Public commemoration took place through a thread of national memorial sites for which a repertory of ritual acts had been developed. The persecution of the Jews had no distinct place in this. There were no public mourning rituals nor did the government recognize separate victim groups except for the heroes of the resistance. There was the occasional flare that sparked controversy, a case dredged up from the past or an ill-formulated statement, but there was no collective language or set of practices. Critical knowledge and sensitivity to the immensity of the mass murder was not simply lacking, but lingered ‘subsumed and subliminal.’2 At best what was later termed Holocaust consciousness was denoted in oblique terms.

It seems that postwar Drenthe, like the country as a whole, with the wave of modernization that flooded the region, sought to leave the past behind as quickly as possible spending no time looking back. ‘In the name of progress, much had to be cleaned up and forgotten,’ as one study on the surge of modernization put it, creating a screen memory ‘cleansed of all sorts of disturbing facts and details.’3 The best illustration is the way in which camp Westerbork was reused and abandoned. First it was employed to incarcerate those eligible for transitional justice, then to house repatriates from Indonesia. Finally, the site was left to ruin. Other prison camps were more suited to the postwar nationalist narrative of oppression and resistance. Until the 1970s, the authorities made no successful effort to recall the Shoah past. It was not until almost all material remains of the Durchgangslager were erased – and made way for a huge observatory – that locals began to turn the site into a memorial.

Still, that is not all that transpired. Postwar dealings with the past were multidirectional, as Michael Rothberg convincingly argued in his groundbreaking study of early Holocaust remembering, though it does require some research to bring this versatility to the surface.4 A parallel can be drawn with urban planners in Emmen who concentrated on modernist construction without losing sight of the inclusion of prevailing landscape elements such as relief, dolmen or residual farms. The surrounding landscape had to penetrate the modern residential areas, as the chief urban planner described his ideal. A slightly elevated street in New Town Emmen could conceal a ridge created by boulder clay carried from the land ice, 150,000 years ago. The same could be said of the immaterial past. In this respect, Emmen offers a fitting introduction to the landscape of memory in the 1950s, a period in which the Holocaust, as it is now understood, was not yet part of public discourse, but in which seemingly incidental performative acts might leave indelible impressions. A Greek tragedy performed by pupils of a grammar school could thus summon up more recent horrors of war.

After the war, the municipal lyceum was opened to students who wished to take a classical education, including Latin and Greek. Children of peat workers became first-generation lyceum pupils. The school was housed in a temporary timber structure, but included a classical portico, with its distinctive columns, pediment and peristyle. In front of the school was a fountain where the music-making forest god Pan resided. An auditorium was built next to the school to support the civilizing strategy.5

To celebrate the opening of the auditorium, the talented writer Harry Mulisch was invited. It wouldn’t be long before he successfully remodeled himself as the literary voice of WWII, but that wasn’t yet the case when traveling to Emmen. Mulisch was born in 1927 from parents living in exile. His father grew up in Bielitz, near Auschwitz, which was part of the Austrian part of the Danube Monarchy. He came to live in the Netherlands after WWI, where he met his wife, born from a Frankfurt Jewish family. In WWII, father collaborated with the German forces but made sure that mother and son weren’t deported. The author summed it up in the aphorism that he was born from WWI and embodied WWII. In 1957, Harry Mulisch was the first recipient of the Anne Frank Prize that the Hacketts initiated on the basis of their script’s royalties. One year later he was appointed as a jury member and 30 years later he confessed that he had only started reading Anne’s diary because of an invitation to the presentation of the critical edition in 1986.6

In January 1954, the young writer was on his way to Emmen, sharing his travel experiences with the readers of an intellectual weekly. ‘The old locomotive groaned, pulling its dusty carts … through the ancient land of Stone Age man and bog corpses … until the end of the world.’ Arriving dusty and tired, Germany turned out to be alarmingly close. ‘God forbid!’ But what a surprise. The scales fell from his eyes. Once a desert, Emmen had been transformed into an oasis of modern architecture. The auditorium exceeded Mulisch’s wildest expectations.

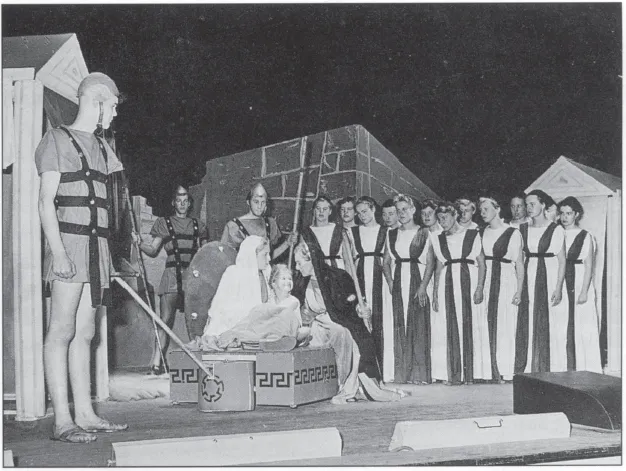

In the first week of September 1955, the school staged Trojan Women in the same auditorium. This play by the ancient Greek playwright Euripides told of the aftermath of the Greco-Trojan War when all male Trojans have been killed and the remaining women are to be taken as spoils of war. The teachers had managed to get Karl Guttmann, who was employed by the prominent theater ensemble De Haagse Comedie, to travel up north and direct just under 30 pupils for three performances – one year before he directed the Anne Frank play.

Two hundred kilometers seems a short distance; but for the centrally organized Dutch theater world, it was unheard of to cross the threshold to ‘the province,’ let alone Drenthe. Jules Croiset, who would take on the role of Peter when the company passed Emmen on March 18, 1957, still remembers the intimate auditorium, but also the long two-lane road to it and the even longer journey back.7 Mulisch wasn’t the only visitor who thought no further than dolmen and peat. Cultural decentralizat...