![]()

PART I

Scientific Knowledge and Scientific Inquiry

Avicenna’s theory of science is concerned with two kinds of scientific knowledge, conceptions and assertions, and with a number of fundamental questions that articulate the basic types and the order of scientific inquiry. Each stage in the process of inquiry corresponds to a particular kind of question. What is the meaning of a term? What is the essence of an object? Does a certain subject exist? Does a subject have a certain attribute? Why does a subject have a certain attribute? Answers to such questions come systematically in the form of distinctive types of conceptions or assertions.

Ideas and problems from Aristotle’s theory of science are translated by Avicenna into the language of conception and assertion in a dynamic process of transformation of the doctrine of the Posterior Analytics. If all teaching and all learning involving reason presuppose some form of preexistent knowledge, conception and assertion are the characteristic elements into which such knowledge may be analyzed. The scientific knowledge of a conclusion acquired by demonstration is equivalent to its justified assertion. And the assertion of a conclusion requires the prior conception and assertion of its premises as well as the prior conception of the conclusion itself.1 Classical problems of Aristotelian epistemology are also investigated by Avicenna through the lens of conception and assertion. Objections against the possibility of inquiry (Meno’s paradox) and against the possibility of scientific knowledge (skeptical arguments pointing to the inevitability of infinite regress or circular reasoning) are formulated—and solved—in a language whose constitutive elements are conceptions and assertions. At the same time, new problems arise as a result of Avicenna’s interventions on the Aristotelian framework. How does the distinction between potential and actual knowledge play into his broader set of admissible logical forms? Again, if the process of search for principles must inevitably come to a stop, what do primary and immediate conceptions and assertions look like? And how do we come to know them? Conceptions and assertions are the provenance and destination of scientific reasoning. In a science both the starting points and the things that are sought fall in one category or the other. Complex conceptions are acquired by definition and description, starting from simpler, immediate conceptions that are ultimately acquired by abstraction from the domain of perception, while derivative assertions are acquired by demonstration from various kinds of immediate assertions (chapter 1).

The identification of the epistemic character of the basic kinds of immediate assertion is a central component of Avicenna’s theory of science. The distinction between certain and non-certain assertions isolates the domain of scientific discourse from other domains of nonscientific or prescientific discourse. Certainty is the distinctive mark of scientific assertions—immediate and non-immediate alike—and a constitutive element in the definition of demonstration (a deduction consisting of premises that are certain and entailing a conclusion that is also certain). Avicenna’s account of certainty is in turn dependent on the notion of belief and requires a combination of truth and necessity. And the certainty of immediate assertions that serve as principles of scientific deductions is associated with different kinds of necessity and with different sources. Such necessity may be epistemic or ontological, and its sources may be either internal, as in the case of primary propositions like the law of the excluded middle, or external, as in the case of evident propositions based on perception or experience. A classification of deductive principles based on their epistemic status and the corresponding division of arguments based on the epistemic status of their premises and conclusions allows Avicenna to cast a wide net over different forms of reasoning encountered in the process of scientific inquiry as well as in the rejection of competing theories. In this connection, the classification of nonscientific statements (assertions that may mistakenly be held to be true—or even necessary—just because they are widely accepted) or pseudo-scientific statements (assertions based on estimations that are false but may nonetheless appear compelling) is an integral part of Avicenna’s epistemological project (chapter 2).

Scientific inquiry involves three main groups of questions. The first group of questions is concerned with whether something exists or whether a subject has a certain attribute. Do physical qualities exist? Do circles exist? Are humans capable of laughter? Are triangles such that the sum of their internal angles is equal to two right angles? The first two examples fall in the category of what Avicenna calls simple if-questions (hal basīṭ), while the last two examples fall in the category of what he calls compound if-questions (hal murakkab). The first group is therefore associated with two basic kinds of assertions: existential and predicative. The second group of questions is concerned with what a term means or what constitutes the essence of an object. What is the meaning of “even times even”? What is the meaning of “void”? What is an eclipse? What is a triangle? The first two examples fall in the category of what-questions relative to the meaning of a name (mā bi-ḥasab al-ism), while the last two examples fall in the category of what-questions relative to the essence of an object or event. The second group is therefore associated with two different kinds of conceptions: nominal definitions (or descriptions) and real definitions. The third group of questions is concerned with why something exists or why a certain attribute belongs to a subject. Why do circles exist? Why do the four elements exist? Why are broad-leaved plants deciduous? Why does the moon undergo eclipses? The first two examples fall in the category of why-questions relative to the existence of a subject, while the last two examples fall in the category of why-questions relative to whether a subject has a certain attribute. The third group is associated with the same kinds of assertions as the first group (existential and predicative), which in this case answer a why-question rather than just an if-question. The taxonomy of scientific inquiry and its types of questions (if-questions, what-questions, why-questions) is accompanied by a rigorous account of their relative order, ranging from the simple identification of the meanings of terms in a science to the establishment of the existence of subjects, the investigation of the essences of subjects and attributes, the investigation of the necessary attributes of subjects, and the identification of the causes in virtue of which those necessary attributes belong to their subjects (chapter 3).

![]()

1

Conception and Assertion

THE TWO PATHS OF SCIENTIFIC KNOWLEDGE

The distinction between conception (taṣawwur) and assertion (taṣdīq) is a characteristic feature of Arabic logic. Conception is primarily concerned with the sort of knowledge involved in concept formation and in the analysis of concepts, terms, definitions, and descriptions. Assertion is concerned with the sort of knowledge involved in the ascription of truth to propositions and in the analysis of deduction and demonstration.1

Avicenna is neither the first nor the last in this tradition to use conception and assertion as building blocks of logic and, more specifically, as basic elements of a logic of scientific reasoning. Alfarabi before him employs the two notions extensively in his own account of demonstration and definition and understands the internal organization of “material” logic in Aristotle (the five sections of the Arabic Organon coming after the Prior Analytics) to depend on an underlying classification of different types of assertions.2 In Avicenna, however, the use of the distinction becomes pervasive and its significance systematic, so much so that in post-Avicennan logic conception and assertion coalesce into a central theme of discussion and, starting in the thirteenth century, are regularly listed among the candidates for the proper subject matter of logic itself.3

The distinction between conception and assertion plays a foundational role in Avicenna’s theory of science and marks the boundary between two distinct but intimately connected modes of scientific knowledge (ʿilm).4 At the beginning of the section on demonstration in the Nağāt, he writes:

Text 1.1: Nağāt I, 102 (i)–(ii), pp. 112.5–113.1 (Ahmed 2011, p. 87, transl. modified; cf. also Gutas 2012, p. 395)

All scientific knowledge is either [(a)] the conception of some notion or [(b)] assertion. Conception may exist without assertion, for example when one has a conception of the statement that void exists without asserting it, or when one has a conception of the notion of human, in which case (as with any simple [notion]) there is no assertion or denial.

Every assertion and every conception are either [(bb)–(ab)] acquired through investigation or [(ba)–(aa)] exist at the beginning. Assertions are acquired [(bba)] through deduction and [(bbb)] through things we have mentioned that resemble it. Conceptions are acquired [(aba)] through definitions and [(abb)] through other things that we will mention.

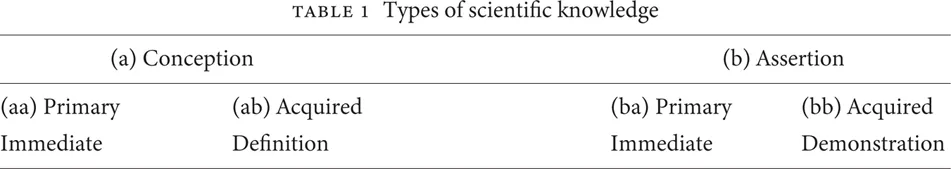

In Text 1.1, conceptions and assertions are identified as the two fundamental types of scientific knowledge. Each of them is further divided into two classes: conceptions and assertions that are acquired through investigation (yuktasabu bi-baḥṯ), as opposed to conceptions and assertions that exist in some primary way at the beginning of the process of inquiry (wāqiʿ ibtidāʾan). Investigation is a technical term in Avicenna’s logical vocabulary alluding to the articulation of a discursive line of reasoning (naẓar is often used in a similar sense). In this passage, it means two distinct things. In the case of assertions, acquisition through investigation means acquisition through deduction (direct or indirect) and other argument forms such as induction, example, or enthymeme discussed in the treatment of formal logic. In the case of conceptions, acquisition through investigation means acquisition through definition or description, whose rigorous theoretical treatment is the prerogative of the theory of science (as opposed to dialectic). It is important to note that the distinction between what is acquired through investigation and what is not acquired through investigation in Text 1.1 is not a distinction between acquired and innate (Avicenna vigorously rejects innatism) but rather one between different kinds of objects and modes of acquisition. According to this preliminary characterization, illustrated in table 1, scientific knowledge turns out to be one of four things: (aa) a primary conception, (ab) an acquired conception, (ba) a primary assertion, or (bb) an acquired assertion.5

The distinction between acquired and non-acquired conceptions and assertions is critical for the formulation of Avicenna’s own version of epistemological foundationalism, namely the doctrine that scientific knowledge ultimately presupposes indemonstrable first principles on which everything else depends. In other words, in order for scientific knowledge to be possible, there must be (i) immediate assertions that are not grounded in other assertions and (ii) immediate conceptions that are not in turn dependent on other conceptions. In the continuation of Text 1.1, Avicenna evokes the fatal threat of an infinite regress to argue that the process of acquisition of conceptions and assertions must come to a stop at immediate items of each kind:

Text 1.2: Nağāt I, 102 (iii), p. 113.2–6 (Ahmed 2011, pp. 87–88, transl. modified; cf. also Gutas 2012, p. 395)

Deductions have parts that are asserted and others that are conceptualized, while definitions have parts that are conceptualized. This does not result in an infinite regress, in such a way that knowledge of these parts becomes available only through the acquisition of other parts whose ...