![]()

CHAPTER 1

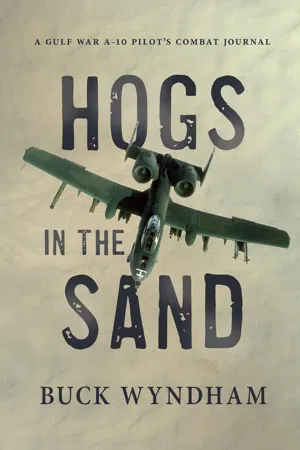

The Hog

“You can get much further with a kind word and a gun than you can with a kind word alone.”

—Al Capone

THEY HAD TO BE some kind of battle-worn X-Wing fighter planes from Star Wars. That was the first explanation my 11-year-old mind came up with as I stood on the beach with my family in South Carolina. My sister and I had been building a sandcastle while my parents snoozed in their beach chairs. I’d glanced up though sun-glistened eyes to see a pair of sinister aerial shapes, skimming low along the surf line from south to north in loose formation. To my young mind, they looked brutal, primitive, otherworldly, and exotic—like a dinosaur come to life.

The apparitions whistled out of sight in the summer haze, and I knew I must figure out what they were. It took me another couple of months to learn their identity from a copy of Aviation Week magazine in my school’s library. From that day on, I was hooked on the A-10 and pledged to myself I would one day be an A-10 pilot. I didn’t have any idea how to accomplish that lofty goal, but I had plenty of youthful energy to dream and doodle and dream some more. My path was charted, then and there.

As I grew up, I educated myself about the A-10. I learned it was the Air Force’s best ground-attack fighter, and that although its official name was the Fairchild-Republic A-10 Thunderbolt II, everyone who flew it or maintained it called it, affectionately, the “Warthog” or just the “Hog.”

I learned its primary mission, Close Air Support, involved a lot more than just blasting armored vehicles with its enormous seven-barreled, 30-millimeter Gatling gun—a gun that fired armor-piercing bullets the size of a large flashlight. I learned that the Hog also carried a multitude of other weapons and performed other roles I hadn’t even heard of. I learned that flying low over a battlefield means constantly getting shot at, a fact that did not dampen my youthful enthusiasm for flying it. The Hog, I learned, was designed to survive—and that cemented my interest even more.

Everything I did in high school and college had a filtered image of a pair of silver Air Force wings superimposed over it. I relentlessly studied aviation and participated in every flying opportunity I could find, from launching radio-controlled gliders to towing advertising banners in a vintage Piper Cub.

One by one, I jumped through the thousands of required hoops, and in the fall after college graduation, I found myself entering US Air Force pilot training in west Texas.

Some of my classmates in pilot training thought I was nutty for listing “A-10” as my first selection on my assignment request form. Most of the guys who wanted to be a fighter pilots coveted the sleeker, more glamorous F-15s and F-16s. But for me, the mental image of flying low, dodging hills and trees, and unleashing holy hell with that giant aerial cannon still seemed like the best job ever.

A year of intense flight training followed and, by a stroke of luck, grace, and perhaps some preordination, I was awarded an A-10 assignment along with the silver wings of an Air Force pilot. That began another year of equally rigorous training that led to me to become fully mission-qualified in the A-10.

I don’t have to tell you how good that day was.

* * * * *

A description of the A-10 Warthog’s appearance always includes one prominent word: mean.

In addition to the world’s most powerful forward-firing aircraft-mounted gun protruding from its snout, the Warthog’s thick, Hershey-bar-shaped wings could carry a vast assortment of bombs, rockets, and missiles. The plane was designed to kill just about anything on a battlefield, especially tanks and armored vehicles.

A plane designed to be pitted against such a monstrous, hulking target as a battle tank is, appropriately enough, not sleek. Nor is it fast compared to traditional fighters and attack airplanes. Aerodynamic smoothness and graceful lines were distant-last-place criteria in the engineer’s minds when they designed the A-10. But despite its looks and relatively slow speed, it was an astonishingly maneuverable airplane to fly and attractive in its own way.

The Hog’s mission was close air support (CAS)—supporting ground troops by shooting at nearby enemy forces. It was an extremely demanding mission because it meant most of our time was spent hiding at low altitude, maneuvering violently to avoid enemy fire, dodging hills and trees, reading road maps, plotting enemy and friendly troop positions, and most importantly, employing our weapons against the enemy, who may be only yards away from the good guys.

As you might guess, “friendly-fire” incidents, where a pilot mis-identifies and accidentally shoots at friendly troops, were a constant dread in the A-10 community. We feared this as much as enemy fire and we took extensive precautions to prevent it.

Flying an A-10 down low, in a high-workload flying environment, we had to concentrate on what we were doing every millisecond because, although A-10s operated in pairs, we were single-seat pilots, alone in our own airplanes. Other than one early test article on display in a museum, there were no two-seat A-10s.

“Single-seat” is much more than just an aircraft description or broad designation. For A-10 pilots, it’s an attitude and a philosophy. It means you are completely in charge of your destiny. Everything the airplane does and whatever is sent into oblivion by your bombs, missiles, and bullets went there because you alone made it happen.

Let me put you in the cockpit for a moment.

When you’re in initial Air Force pilot training, you fly only two-seat training airplanes. You get to fly solo, without an instructor, only a couple dozen times. And even when you’re solo, you feel your instructor’s presence in the unoccupied seat, guiding and correcting you.

A year or so later, when you’re flying an A-10 for the first time, you are constantly reminded that you’re very much on your own. Your instructor is nearby in another airplane, but your first flight in the Hog is also your first solo flight in it. It’s a sobering event, but immensely and unforgettably fun, too.

Some modern fighters and attack airplanes have a second crewmember—a weapons-system operator, a radar intercept officer, or a bombardier. Those crews develop their own flying styles, pacing, and tactics, optimized for two people. As an A-10 “Hog Driver,” however, you’re obligated to develop your own habit patterns. You quickly perfect a system of personal cross-checks and behaviors that will keep you alive, despite the many internal and external factors that affect you (and distract you) each time you fly.

In time, you begin to feel a profound sense of freedom in being alone in a multi-million-dollar attack jet, highly trained and armed to the hilt. Your wingman or Flight Lead is usually flying nearby, of course, and there are numerous operational rules you must follow, but when you look around the cockpit of an A-10, you’re always reminded that you’re completely alone. The cockpit is a small space, designed not for comfort, but for utility. It’s your life-pod, your cocoon, and your office. When you reach for the master arm switch so you can fire an anti-tank missile right down the throat of some Commie bastard, it’s as natural an action as a corporate executive reaching across his desk for a paperclip.

An A-10 cockpit fits your body. Every switch and control is placed so you can reach it without stretching. The stick grip in your right hand is molded to the human palm, and the trigger and four buttons on it are placed in natural positions under your fingers. The twin throttles under your left hand are also contoured to fit your palm, and on them are more buttons, each under a different finger. Your legs disappear deep into dark wells on either side of the center instrument pedestal, and your feet rest comfortably on the rudder pedals. Your life-support system, communication system, and restraint harness connect your body to the airplane in seven places. The result of all this contact is a strong sense that you’re not just sitting in the airplane; you’re a part of it. You don’t sit in the cockpit, you strap the airplane on, like a backpack. The airplane is an extension of your body.

When you roll in on a target to drop a bomb from a thirty-degree dive angle, you do not do what the book says you should do. The book instructs you to perform the dive-bomb roll-in maneuver by moving the control stick to the side until the aircraft’s angle of bank is approximately 120 degrees. Then you’re supposed to pull the airplane’s nose downward until it’s approximately thirty degrees below the horizon, move the stick back to the other side to roll the airplane upright, and begin your alignment with the target.

In practice, that’s not the way it’s done. You simply roll your body in the direction of the target and fly your body down a thirty-degree path to the target. Instead of “placing the aiming pipper over the predetermined aim-off distance and maintaining the dive angle until the pipper covers the target,” you simply maneuver yourself in the proper direction, look at the target, and command it to die. When you start thinking this way, you know you’ve finally become comfortable with the airplane and the mission. You and the airplane are “one.” The military’s huge training expenditure is now validated, and woe be to the enemy.

* * * * *

One of the first things they taught us in A-10 school was that the Hog was designed to survive and bring us home safely, despite suffering severe battle damage. The ground-school instructors explained how the high-bypass turbofan engines ran cool and didn’t emit much hot exhaust. The limited amount of hot air they did produce was masked from view by the horizontal stabilizers. This design feature meant that any heat-seeking, infrared-guided missiles coming our way would have difficulty locking onto the engines and their warm exhaust plumes. The engines were placed outside the fuselage and far apart, so if one of them was hit, the resulting fire or shrapnel wouldn’t damage the other one or any other critical aircraft system.

Next, the flight control cables that moved the ailerons, rudders and elevators were routed along widely spaced paths from the cockpit to their respective hydraulic control actuators, so if a bullet severed one cable, it wouldn’t take out any other one.

But let’s imagine the unthinkable. Let’s say an enemy missile struck my airplane, destroying the tip of my left wing and jamming my left aileron so it couldn’t move. Let’s also suppose that hydraulic fluid was spraying out of the damaged flight control actuator. In most modern airplanes, I’d be in big trouble, not only because of the jammed aileron and the resulting lack of control ...