![]()

When Swedish soprano Jenny Lind appeared at the recently opened St. Lawrence Hall on Tuesday, October 21, 1851, it is quite likely that she was the first international star to visit the city. Toronto’s population was just 30,000, the streets were not paved, and a railway had not yet been built to link the city directly to hubs in the United States. One has to assume that Jenny Lind and her accompanists arrived in Toronto by stagecoach. It is sobering to realize that just 17 years earlier the city of Toronto had been known as the town of York and that Confederation was still 16 years down the road! In light of this, the fact that the performance even happened seems like a miracle.

Born in 1820, Lind was known as the “Swedish Nightingale” and had achieved substantial fame in Europe when American impresario P.T. Barnum approached her about touring the United States. Lind only agreed to embark on such an adventurous undertaking when Barnum offered her what, for the time, was a fortune, which Lind used, not for her own gain, but to fund free schools back home in Sweden. Barnum, a promoter nonpareil, was able to generate so much publicity for Lind’s performances that at many shows tickets were sold by auction.

Toronto clearly caught the fever. Lind’s name appeared in the Globe 91 times in 1850 alone! The first mention of the tour was in March 1850, and the tour was considered significant enough that the Globe reviewed the opening show in New York that September. The American press dubbed the phenomenon “Lindmania,” some 113 years before the advent of Beatlemania!

Lind played 93 shows for Barnum before deciding to continue the tour on her own. The Toronto show was booked under the auspices of Lind herself and, even with a steep price for the time of three dollars a ticket (this equals about $125 in 2019; well into the early 20th century, most theatres could not charge more than one dollar for a ticket to any kind of performance), was so successful that she added additional shows on the Wednesday and Thursday. For a town of just 30,000 residents, the event was talked about for years after.

In the second half of the 19th century, entertainment in Toronto consisted largely of minstrel, Wild West, and vaudeville shows. In many respects, the advent of blackface minstrel song and dance numbers by solo performers in the 1820s marked the beginning of the American music industry. A particularly ugly phenomenon, the early minstrel shows featured white men applying burnt cork to their faces so as to appear black. They would then caricature African Americans, portraying them as slow-witted and happy on the plantations, where they would sing, dance, and eat watermelon and chicken all day. As reprehensible as these shows were, they introduced African American music, albeit not necessarily in a completely authentic form, to white audiences in the north.

According to Lorraine Le Camp in her 2005 dissertation “Racial Considerations of Minstrel Shows and Related Images in Canada,” the first blackface performers to appear in Toronto came to town with the circuses. She lists such performances as taking place in 1840 (only six years after Toronto was incorporated as a city!), 1841, 1842, and 1843. Unfortunately, the venues or the exact dates of any of these performances are not known.

These were probably not the first local blackface performances. According to an article in the Toronto Star in June 2018, as early as July 20, 1840, Toronto’s small (the black population in Toronto in 1855 was 539 residents; in 1840 it would have been considerably smaller) but obviously politically aware black populace, largely comprised of former African American slaves, petitioned city council to refuse to license circuses that included blackface performers to set up within city limits. The petition stated that such performances made “the Coloured man appear ridiculous and contemptible,” and led to “contaminating the wholesome air of Our City with Yanky [sic] amusement of comic songs known by the name of Jim Crow and Aunt Dinah.” The petition was sadly unsuccessful.

Similar petitions were submitted over the next three years, but it was only when an 1843 petition pointed out that the city of Kingston had already banned such shows, that Toronto’s city council fell in line and for a short time refused to license such performances. The city’s refusal to license minstrel acts, unfortunately, did not last very long.

In 1849, the Ethiopian Harmonists appeared at the Royal Lyceum on King Street (the word Ethiopian was commonly used by blackface minstrel troupes to try to convey the idea that they were somehow authentically representing black culture). The Lyceum was the first purpose-built theatre in Toronto, and the performance by the Ethiopian Harmonists was the debut appearance by a minstrel ensemble (as opposed to a solo performer in blackface) in Toronto. It was only six years earlier that the Christy Minstrels and the Virginia Minstrels staged the earliest concerts by full minstrel ensembles in Buffalo and New York City respectively.

Toronto was quick to embrace this new form of entertainment. In May 1850, the Nightingale Ethiopian Serenaders of Philadelphia played the Royal Lyceum (advertisements for the show stressed that the first part of the performance was in whiteface while the second and third parts were in blackface) and White’s Serenaders (noted in newspaper advertisements as “Splendid Ethiopian Entertainment”) came to the Lyceum in July of that year. In 1851, more than a half-dozen minstrel ensembles played at either the Lyceum or Temperance Hall.

Such performances continued unabated for the next several years at these two venues, as well as at St. Lawrence Hall, the City Theatre, the Music Hall, and Yorkville Town Hall. Notable among these were appearances by the most famous blackface minstrel troupe, the Christy Minstrels, in 1856 and 1861. The second most important minstrel troupe, the Virginia Minstrels, wouldn’t get to Toronto until 1898, when minstrelsy as professional entertainment was on the wane. In 1855, Thomas “Daddy” Rice, known as the father of American minstrelsy and the actor who first developed the Jim Crow character, played the Royal Lyceum for a week. Toronto’s own internationally famous blackface minstrel star, Colin “Cool” Burgess, was featured with Sam Sharpley’s Minstrel Troupe at the Music Hall in November 1863.

There were also a number of performances of stage adaptations of the Harriet Beecher Stowe abolitionist novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin in Toronto. A number of these adaptations changed the nature of the story to support slavery and were also done in blackface. The first such production in Toronto appears to have been in June 1853, again at the Royal Lyceum.

After the Civil War ended in 1865, newly freed African Americans began to form minstrel companies of their own, and quickly came to dominate the industry. While African American blackface minstrels still had to satirize aspects of black culture to appeal to white audiences, such troupes supplied a vehicle for talented black actors and singers to work in showbiz rather than to farm or work other labour-oriented jobs. It also gave them some control over the authenticity of both the music and the satire.

The earliest appearance of an African American blackface minstrel troupe in Toronto that we found took place in the year following Confederation, when an ensemble called the Georgia Minstrels performed at the Music Hall on November 21, 1868. A writer for the Globe seemed impressed, while his review suggested that he had seen a minstrel show before: “The musical part of the entertainment was interspersed with the usual oddities attachable to Negro music, which, of course, made the audience laugh to their heart’s content.”

The Georgia Minstrels returned to the city four times through the 1870s, usually performing for two or more nights at the Royal Opera House. In 1875, they were billed as “The Original Georgia Minstrels (and Brass Band) and The Great Slave Troupe and Jubilee Singers.” In 1878, the advertisements for their shows mentioned that Billy Kersands, one of the most famous of all African American minstrel performers, would be appearing with the ensemble. Later in the year they returned to Toronto, billed as Callender’s Georgia Minstrels. At the time, there was more than one troupe touring as the Georgia Minstrels, the word Georgia having become code, meaning that the ensemble was black. In 1879 the group was billed as Sprague’s Original Georgia Minstrels. It was led by the great composer and bandleader James Bland, who was perhaps second only to Kersands in African American minstrel show fame.

Rivalling Callender and Sprague in the minstrel business was J.H. Haverly’s many white and African American blackface touring ensembles. Modelling himself on P.T. Barnum, Haverly was a master at publicizing his troupes via hyperbolic newspaper ads and broadsides. Haverly’s Minstrels, an African American troupe, first appeared in Toronto in June 1877 at Mrs. Morrison’s Grand Opera House. In December 1879 he brought his white United Mastodon Minstrels to the Royal Opera House for three nights. Two months later his Genuine Colored Minstrels played the Grand Opera House. Various Haverly ensembles, including the intriguingly named Haverly Strategists, came to Toronto on a regular basis through 1905.

Other African American blackface minstrel troupes, such as Emerson’s Mecatherian Minstrels and Sam Hague’s British Minstrels, played both the Royal Opera House and the Grand Opera House in the 1870s and 1880s.

In December 1898, a white theatrical troupe, Primrose and Dockstader’s Minstrels, appeared for three nights at the Grand Opera House. The difference in the minstrel shows put on by black and white performers is easily gleaned from the following sentence in the Globe’s review where they commended the performance of “Mr. George Primrose in his watermelon song, in which four pickaninnies gave a laughable cakewalk.”

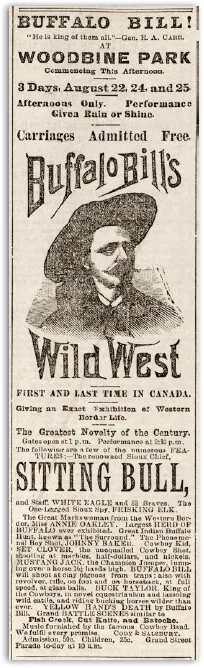

August 22, 24, 25, 1885, Woodbine Park

Primrose and Dockstader’s Minstrels came back to Toronto in December 1899. By 1903 the duo had split up and Lew Dockstader returned to town with “his Great Minstrel Company” to play the Princess Theatre at the end of the summer. Dockstader would return to the Princess Theatre several times through 1909. Given that Torontonians bought tickets to see touring troupes on a regular basis for 60 years, clearly the city’s residents were more than a bit taken with blackface minstrelsy.

Tony Pastor is often considered the grand master of vaudeville largely due to his famous 14th Street Theatre in New York City. He brought his first vaudeville troupe to Toronto in 1875, playing two nights in July at the Grand Opera House. The ad for the performance read “Tony Pastor with His Traveling Company with 10 different acts.” The acts referred to would have included comedians, jugglers, musicians, dancers and various novelty specialties.

In addition to vaudeville, Wild West shows were quite popular. Just as minstrel shows purported to give their audiences a sense of what life was like in the southern United States for African Americans, Wild West shows promised their audiences that they would provide a portal into life in the rugged southwest. One of my favourite advertisements from the period is for Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show, which came to Woodbine Park for three days in August 1885. The ad proclaims that this is the first and will be the last time the show will come to Canada and that the show will provide patrons with “an Exact Exhibition of Western Border Life — The Greatest Novelty of the Century.” It goes on to list among its “numerous features” a “renowned Sioux Chief.”

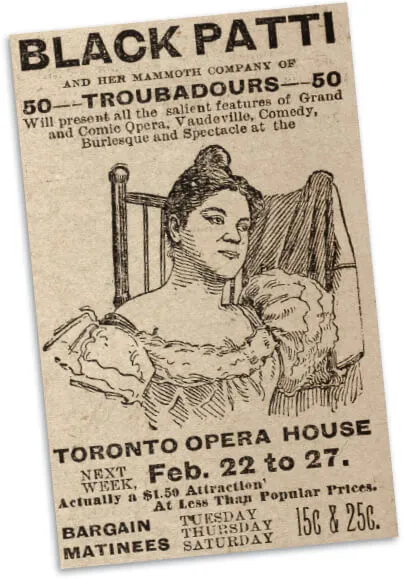

Some 41 years after Swedish soprano Jenny Lind had delighted Torontonians, in September 1892, the famed African American soprano Sissieretta Jones, a.k.a. “The Black Patti,” sang at the Auditorium (formerly Shaftesbury Hall on Adelaide West). In 1897 she returned on two separate occasions to play the Toronto Opera House and the Grand Opera House.

Bob Cole wrote the first full-length musical comedy written and performed exclusively by black Americans, which hit a New York stage in 1898. While there were only a total of eight performances at the Third Avenue Theatre in NYC, the show played for a week that year at the Toronto Opera House and came back for another week at the same venue in 1900. In 1907 and 1908 two more musicals written, directed, and performed by African Americans, Bert Williams and George Walker’s Abyssinia and Bandana Land, each played the Grand for a week.

In 1899, Canadian brothers Jerry and Mike Shea opened the first Shea’s Theatre on the east side of Yonge Street between Adelaide and King. The Sheas would later build a second theatre, known as Shea’s Victoria, at Richmond and Victoria in 1910, and four years later would open Shea’s Hippodrome on the west side of Bay, just north of Queen. With a capacity of 3,200 (some sources say 2,600), the Hippodrome was the largest movie palace in Canada and one of the largest in the world. All three of the Shea’s buildings presented vaudeville shows and eventually movies.

February 22–27, 1897, Grand Opera House

For years, the three Shea’s theatres, along with the Princess Theatre, the Grand Opera House, the Majestic Music Hall, and eventually Loew’s Theatre, presented some of the biggest stars in vaudeville. Ontario native May Irwin had first appeared onstage in New York in 1877 at the Metropolitan Theatre. Having worked for Tony Pastor for many years, she initially became famous for her acting and comedic abilities. By the 1890s she had become a recording star, best known for singing “coon shouting” songs, her biggest hit being “The Bully Song” (also known as “Bully of the Town”). By 1896, she appeared in her first silent film, The Kiss. Considered somewhat risqué at the time, it was the firs...