- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About this book

'Sometimes called coining, spooning or scraping, Gua sha is defined as instrument-assistedunidirectional press-stroking of a lubricated area of the body surface that intentionally creates'transitory therapeutic petechiae' representing extravasation of blood in the subcutis.'Gua sha has been used for centuries in Asia, in Asian immigrant communities and byacupuncturists and practitioners of traditional East Asian medicine worldwide. With theexpansion of traditional East Asian medicine, Gua sha has been used over broad geographicareas and by millions of people. It is valuable in the treatment of pain and for functionalproblems with impaired movement, the prevention and treatment of acute infectious illness, upper respiratory and digestive problems, and many acute or chronic disorders. Research hasdemonstrated Gua sha radically increases surface microperfusion that stimulates immune andanti-inflammatory responses that persist for days after treatment.The second edition expands on the history of Gua sha and similar techniques used in earlyWestern Medicine, detailing traditional theory, purpose and application and illuminated byscience that focuses its relevance to modern clinical practice as well as scholarly inquiry.This book brings the technique alive for practitioners, with clear discussion of how to do it –including correct technique, appropriate application, individualization of treatment – and whento use it, with over 50 case examples, and superb color photographs and line drawings thatdemonstrate the technique.NEW TO THIS EDITION• New chapter on immediate and significant Tongue changes as a direct result of Gua sha• Research and biomechanisms• Literature review from Chinese language as well as English language medical journal database• New case studies• Over 30 color photographsNew chapter on immediate and significant Tongue changes as a direct result of Gua shaResearch and biomechanismsLiterature review from Chinese language as well as English language medical journal databaseNew case studiesFully updated and revised throughoutOver 30 colour photographs

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Gua sha and the history of traditional medicine, West and East

Counteraction medicine: the crisis is the cure

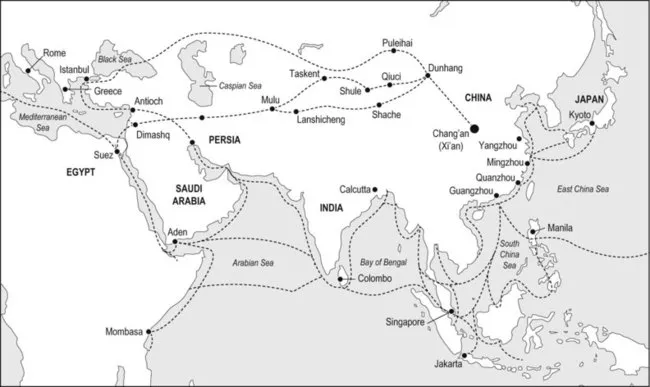

The Silk Road

Hippocrates, Galen and Ch’i Po: humoral medicine

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Biographies

- Foreword

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Chapter 1: Gua sha and the history of traditional medicine, West and East

- Chapter 2: Evidence for Gua sha: A review of Chinese and Western literature

- Chapter 3: Physiology of Gua sha: Western biomodels and East Asian functional perspective

- Chapter 4: San Jiao

- Chapter 5: Sha syndrome and Gua sha, cao gio, coining, scraping

- Chapter 6: Application of Gua sha

- Chapter 7: Immediate and significant Tongue changes as a direct result of Gua sha

- Chapter 8: Classical treatment of specific disorders: location, quality, mutability and association

- Chapter 9: Cases

- Appendix A: Gua sha handout

- Appendix B: List of common acupuncture points by number and name

- Appendix C: Directions for Neti wash and Croup tent

- Appendix D: Tabled articles and studies with full citations: Gua sha literature review

- Glossary of terms

- Color Page

- Index