Pathology and Intervention in Musculoskeletal Rehabilitation - E-Book

- 1,240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Pathology and Intervention in Musculoskeletal Rehabilitation - E-Book

About this book

- NEW! The Skin and Wound Healing chapter looks at the numerous tools available to assist in objectively monitoring and treating a patient with an acute or chronic wound.- NEW! Rotator Cuff Pathology chapter highlights the anatomy, function, and etiology of the rotary cuff, and addresses rotary cuff injuries, physical examination, and non-operative and operative treatment.- UPDATED! Substantially revised chapter on the Thoracic Ring Approach™ facilitates clinical reasoning for the treatment of the thoracic spine and ribs through the assessment and treatment of thoracic spine disorders and how they relate to the whole kinetic chain.- UPDATED! Revised Lumbar Spine – Treatment of Motor Control Disorders chapter explores some of the research evidence and clinical reasoning pertaining to instability of the lumbar spine so you can better organize your knowledge for immediate use in the clinical setting.- UPDATED! Significantly revised chapter on the treatment of pelvic pain and dysfunction presents an overview of specific pathologies pertaining to the various systems of the pelvis — and highlights how "The Integrated Systems Model for Disability and Pain" facilitates evidence-based management of the often complex patient with pelvic pain and dysfunction.- NEW! Musculoskeletal Bone and Soft Tissue Tumors chapter covers common bones tumors, anatomic considerations and rehabilitation, pediatric patients, and amputation related to cancer.- UPDATED! Thoroughly revised chapters with additional references ensure you get the most recent evidence and information available.- NEW! Full color design and illustration program reflects what you see in the physical world to help you recognize and understand concepts more quickly.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Patient Education, Motivation, Compliance, and Adherence to Physical Activity, Exercise, and Rehabilitation

Introduction

The professional’s role in motivation adherence

What is Meant by Motivation, Adherence, and Compliance?

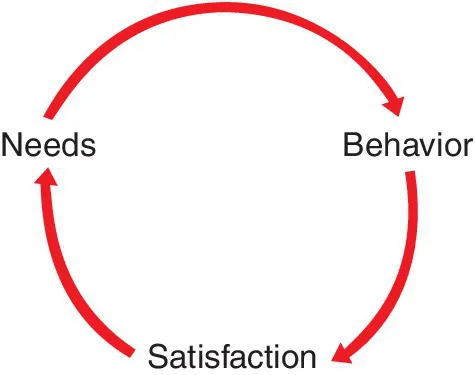

Motivational Theories

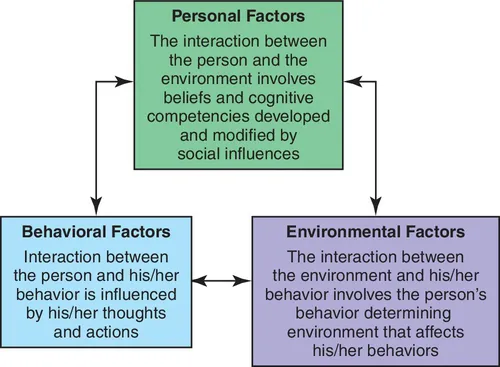

Social Cognitive Theory

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright

- Contributors

- Dedication

- Preface

- Preface

- Chapter 1: Patient Education, Motivation, Compliance, and Adherence to Physical Activity, Exercise, and Rehabilitation

- Chapter 2: The Skin and Wound Healing

- Chapter 3: Cervical Spine

- Chapter 4: Temporomandibular Disorders

- Chapter 5: Shoulder Trauma and Hypomobility

- Chapter 6: Shoulder Instability

- Chapter 7: Rotator Cuff Pathology

- Chapter 8: Shoulder Arthroplasty

- Chapter 9: Elbow

- Chapter 10: Hand, Wrist, and Digit Injuries

- Chapter 11: The Thoracic Ring Approach™: A Whole Person Framework to Assess and Treat the Thoracic Spine and Rib Cage

- Chapter 12: Low Back Pain: Disability and Diagnostic Issues

- Chapter 13: Lumbar Spine: Treatment of Hypomobility and Disc Conditions

- Chapter 14: Lumbar Spine: Treatment of Motor Control Disorders

- Chapter 15: Spinal Pathology: Nonsurgical Intervention

- Chapter 16: Spinal Pathology, Conditions, and Deformities: Surgical Intervention

- Chapter 17: Highlights from an Integrated Approach to the Treatment of Pelvic Pain and Dysfunction

- Chapter 18: Hip Pathologies: Diagnosis and Intervention

- Chapter 19: Physical Rehabilitation after Total Hip Arthroplasty

- Chapter 20: Knee: Ligamentous and Patellar Tendon Injuries

- Chapter 21: Injuries to the Meniscus and Articular Cartilage

- Chapter 22: Patellofemoral Joint

- Chapter 23: Physical Rehabilitation after Total Knee Arthroplasty

- Chapter 24: Rehabilitation of Leg, Ankle, and Foot Injuries

- Chapter 25: Peripheral Nerve Injuries

- Chapter 26: Repetitive Stress Pathology: Bone

- Chapter 27: Repetitive Stress Pathology: Soft Tissue

- Chapter 28: Musculoskeletal Developmental Disorders

- Chapter 29: Pediatric and Adolescent Populations: Musculoskeletal Considerations

- Chapter 30: Management of Osteoarthritis and Rheumatoid Arthritis

- Chapter 31: Systemic Bone Diseases: Medical and Rehabilitation Intervention

- Chapter 32: Muscle Disease and Dysfunction

- Chapter 33: Fibromyalgia, Myofascial Pain Syndrome, and Related Conditions

- Chapter 34: Musculoskeletal Bone and Soft Tissue Tumors

- Index