Facial Trauma Surgery E-Book

From Primary Repair to Reconstruction

- 512 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Facial Trauma Surgery E-Book

From Primary Repair to Reconstruction

About this book

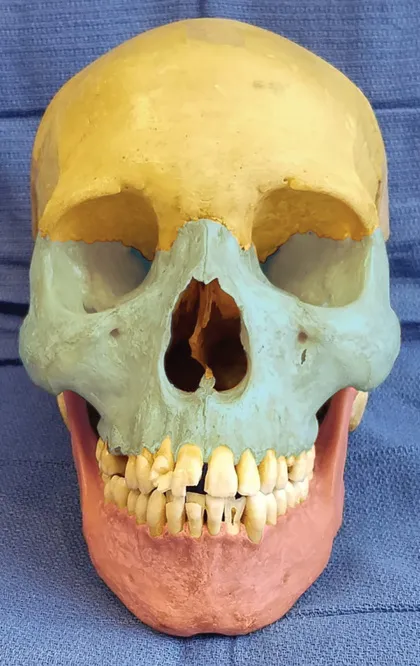

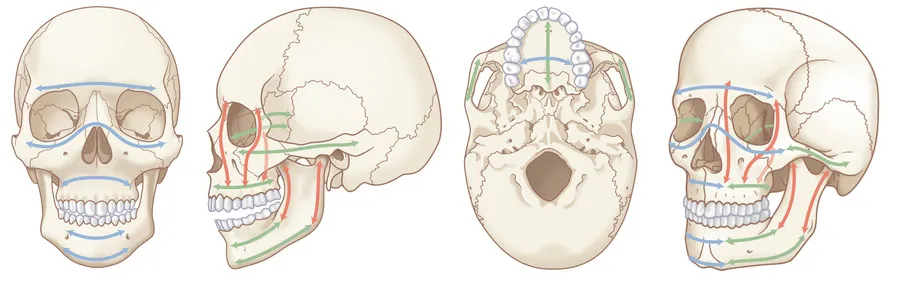

Offering authoritative guidance and a multitude of high-quality images, Facial Trauma Surgery: From Primary Repair to Reconstruction is the first comprehensive textbook of its kind on treating primary facial trauma and delayed reconstruction of both the soft tissues and craniofacial bony skeleton. This unique volume is a practical, complete reference for clinical presentation, fracture pattern, classification, and management of patients with traumatic facial injury, helping you provide the best possible outcomes for patients' successful reintegration into work and society.- Explains the basic principles and concepts of primary traumatic facial injury repair and secondary facial reconstruction.- Offers expert, up-to-date guidance from global leaders in plastic and reconstructive surgery, otolaryngology and facial plastic surgery, oral maxillofacial surgery, neurosurgery, and oculoplastic surgery.- Covers innovative topics such as virtual surgical planning, 3D printing, intraoperative surgical navigation, post-traumatic injury, treatment of facial pain, and the roles of microsurgery and facial transplantation in the treatment facial traumatic injuries.- Includes an end commentary in every chapter provided by Dr. Paul Manson, former Chief of Plastic Surgery at Johns Hopkins Hospital and a pioneer in the field of acute treatment of traumatic facial injuries.- Offers videos that clarify surgical technique, including intraoperative guidance and imaging; transconjunctival approach to the orbit and reconstruction of a zygomaticomaxillary complex fracture; calvarial bone autograft splitting; dental splinting; a systematic method for reading a craniofacial CT scan; and more.- Features superb photographs and illustrations throughout, as well as evidence-based summaries in current areas of controversy.- Enhanced eBook version included with purchase. Your enhanced eBook allows you to access all of the text, figures, and references from the book on a variety of devices.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Assessment of the Patient With Traumatic Facial Injury

Background

Incidence of Facial Trauma in the United States and Worldwide

Patterns of Facial Trauma and Causes

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title Page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright

- Video Contents

- Foreword

- Preface

- List of Contributors

- Acknowledgments

- Dedication

- Section 1 Primary Injury

- Section 2 Pediatric Facial Injury

- Section 3 Secondary Reconstruction and Restoration

- Appendix 1 Evidence-Based Medicine

- Index