- 352 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

"This is a highly enjoyable and well presented book that I recommend for any clinician from student to experienced practitioner. It is suitable for all physiotherapists, manual therapists, sports physiotherapists/therapists, strength and conditioning coaches, sports scientists, athletes and patients who would like to understand, recover and improve their range and ease of movement."

Jimmy Reynolds, Head of Sports Medicine - Academy, Ipswich Town Football Club, Oct 14

- Helps transform thinking about the therapeutic value of stretching and how it is best applied in the clinical setting

- Examines the difference between therapeutic and recreational stretching

- Focuses on the use of stretching in conditions where individuals experience a loss in range of movement (ROM)

- Explores what makes stretching effective, identifying behaviour as a main driving force for adaptive changes

- Discusses the experience of pain, sensitization and pain tolerance in relation to stretching and ROM recovery

- Contains over 150 photographs and 45 minutes of video describing this new revolutionary approach

- Applicable to a variety of perspectives including osteopathy, chiropractic, physical therapy, sports and personal trainers

- Ideal for experienced practitioners as well as those taking undergraduate and postgraduate courses

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Therapeutic Stretching in Physical Therapy by Eyal Lederman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Physiotherapy, Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Introduction to Therapeutic and Functional Stretching

Stiffness and restricted range of movement (ROM) are the most common clinical presentations second to pain. This book is for all therapists and individuals who would like to help others or themselves to recover or improve their ease and ROM. The book aims to provide the know-how to achieve this therapeutic goal with maximum effect.

What Is Stretching?

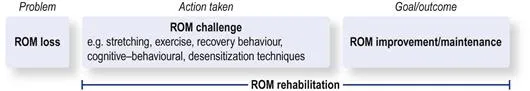

For the purpose of this book stretching is defined as the behaviour a person adopts to recover, increase or maintain their range of movement. This behaviour includes passive and active stretching, which can be in the form of exercise or with the assistance of another person (therapist/trainer). Stretching therefore is the means by which the ROM can be increased, but it is not the only one. There are several ways to achieve ROM improvements depending on the processes associated with the loss of ROM. ROM rehabilitation is perhaps a more suitable term to describe the therapeutic method used to recover/improve movement range. ROM challenge is the term given to all the different methods and techniques that are used to achieve this movement goal (Fig. 1.1).

FIGURE 1.1 Terminology used in therapeutic stretching. ROM, range of movement.

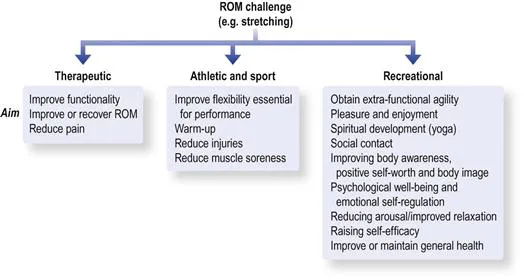

Therapeutic, Sports and Recreational Stretching

Stretching behaviour can be observed in many spheres of human activity. It is often used in sports training as a warm-up, for prevention of injury and to improve sports performance. It is widely used by specialist groups such as athletes and yoga practitioners to develop the high level of flexibility required for performance/practice. Stretching is also used recreationally for general flexibility, enjoyment and self-awareness, as part of spiritual development, and for supporting health and well-being (e.g. yoga, Pilates and t’ai chi). Therapeutic stretching is used predominantly to help individuals to regain functionality that has been affected by ROM losses, and occasionally to alleviate pain (Fig. 1.2).

FIGURE 1.2 Categories of stretching and their aims. Whether these aims are realistic or achievable will be discussed in the book. ROM, range of movement.

Therapeutic stretching, recreational stretching and sports stretching depend on the same biological–physiological processes to promote ROM changes. The differences are in their overall goals (recover ROM or feel great) and the context in which the ROM challenges are applied (in clinic or in a yoga class). The definition of stretching given above can also be used to define ROM rehabilitation or therapeutic stretching.

This book will focus on the therapeutic use of stretching and ROM rehabilitation. However, many of the principles discussed here can be applied to recreational and athletic stretching.

Is stretching essential for normalization of ROM?

It seems that only humans do it; that is, regular, systematic stretching. There is a shared animal and human behaviour of “having a stretch” and yawning called pandiculation. It is often a combination of elongating, shortening and stiffening of muscles throughout the body. Pandiculation tends to occur more frequently in the morning and evening and is associated with waking, fatigue and drowsiness.1 Erroneously, it is assumed that animals use pandiculation as a form of stretch. This behaviour is too short in duration, too infrequent and too specific to a particular pattern to account for general agility. It has been proposed that pandiculation may provide psychological and physiological benefits other than flexibility.1,2

Among humans, only relatively few individuals stretch regularly. Those who stretch tend to focus on particular parts of the body. For example, rarely is the little finger stretched into extension or the forearm into full pronation–supination. So what happens to the majority who do not stretch? Do they gradually stiffen into a solid unyielding dysfunctional mass? And what happens to the parts that we never stretch? Do they stand out as being stiff/range-restricted?

It seems that going about our daily activities provides sufficient challenges to maintain functional ranges; otherwise, we would all suffer from some catastrophic stiffening fate. This suggests that stretching is not a biological–physiological necessity but perhaps a socio-cultural construct. We stretch because it provides special flexibility, it is fashionable and enjoyable (for some), and some believe that it is essential for maintenance of healthy posture and movement. There may be other benefits to recreational stretching such as improving body awareness, positive self-worth and body image, psychological well-being, reduced arousal/improved relaxation, emotional self-regulation and raising self-efficacy.

However, the most important message from the discussion so far is that functional movement, the natural movement repertoire of the individual, is sufficient to maintain the normal ROM. It suggests that ROM rehabilitation, in its most basic form, should put an emphasis on return to pre-injury activities, whenever possible.

Is stretching useful therapeutically?

Recovering ROM becomes important when a person is unable to perform normal daily activities, often as a result of some pathological process that results in range limitation. So there is an obvious need for ROM rehabilitation, but the question is which ROM challenges are most effective?

It has been assumed for a long time that traditional stretching approaches can provide effective ROM challenges. This assumption was supported by numerous studies demonstrating that in healthy young individuals regular stretching results in ROM improvements. Since the biological processes for ROM improvements are similar to those for recovery, the logical conclusion was that stretching is clinically useful. However, only in the last decade has the use of stretching been explored clinically, as a treatment for contractures after joint surgery, neurological conditions and immobilization. The outcome of these studies was summarized in 2010 in a systematic review (35 studies with a total of 1391 subjects).3 It was found that in the short term stretching provides a 3° improvement, a 1° improvement in the medium term and no influence in the long term (up to 7 months). These findings were similar to all stretching approaches, active or passive. Let us assume for the sake of discussion that these reviewers underestimated the effects of stretching. Stretching will still be clinically irrelevant even if these results are doubled (6° and 2°) or tripled (9° and 3°).4 Such modest changes would be meaningless as far as functional activities are concerned;5 most patients (in my experience) would consider this outcome a treatment failure.

The erosion of belief in the usefulness of stretching is also seen in other areas. Stretching as a warm-up before and after exercising has failed to show any benefit for alleviating muscle soreness. It provides no protection against sports injuries and vigorous stretching before an event may even reduce sports performance.6–16 It was demonstrated that strength performance can be reduced by 4.5–28%, irrespective of the stretching technique used.17,18

One reason that stretching was not shown to be useful in all these areas may go back to biological necessity. If it was beneficial we would expect Nature to have “factored-in” stretching as part of animal behaviour, in particular if it improved performance. Yet, with the exception of humans, no animal performs any pre-exertion activities that resemble a stretch warm-up. Lions do not limber up with a stretch before they chase their prey, and reciprocally the prey does not halt the chase for the lack of a stretch. The stretch warm-up in humans seems to be largely ceremonial. A person would stretch in the park before a jog but would not consider stretching to be important for sprinting after a bus. A person may stretch before lifting weights in the gym but a builder is unlikely to stretch, although they may be lifting and carrying throughout the day. The point made here is that we have evolved to perform maximally, instantly and without the need to limber up with stretching. There seems to be no biological advantage in stretching nor is it physiologically essential.

The ineffectiveness of stretching leaves us with the clinical conundrum of how to recover ROM losses. We do know that most of the time people do recover their ROM losses after conditions such as immobilization, surgery, disuse and even frozen shoulder. If they do not do this by stretching, some other phenomenon must account for the recovery; but what is it and can it guide us to a more effective ROM rehabilitation?

Towards a Funct...

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Dedication

- Front Matter

- Copyright

- Preface

- Chapter 1. Introduction to Therapeutic and Functional Stretching

- Chapter 2. Functional and Dysfunctional ROM

- Chapter 3. Causes of ROM Loss and Therapeutic Potential of Rehabilitation

- Chapter 4. Adaptation in ROM Loss and Recovery

- Chapter 5. Specificity in ROM Rehabilitation

- Chapter 6. The Overloading Condition for Recovery

- Chapter 7. Exposure and Scheduling the ROM Challenge

- Chapter 8. Rehabilitating the Active ROM: Neuromuscular Consideration

- Chapter 9. Pain Management and ROM Desensitization

- Chapter 10. Stretch-tolerance Model

- Chapter 11. Psychological and Behavioural Considerations in ROM Rehabilitation

- Chapter 12. Towards a Functional Approach

- Chapter 13. Demonstration of Functional Approach in ROM Rehabilitation

- Chapter 14. Summary

- Index