- 672 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Contact Lenses

About this book

Completely revised with the latest advances, evidence, and standards needed for everyday practice, Contact Lenses, 6th Edition, remains a definitive work on this multi-faceted topic, ideal for optometrists, dispensing opticians, ophthalmologists, and contact lens practitioners. This classic, superbly designed text is perfectly suited for health care professionals, providing all of the essential knowledge needed in one convenient volume.

- Provides up-to-date, authoritative information on contact lens materials and lens types, treatment in contact lens and tear film complications, and myopia correction and contact lenses for abnormal ocular conditions.

- Discusses current topics such as miniscleral lenses, keratoconus, corneal cross linking, and paediatric, cosmetic and prosthetic contact lenses.

- Contains high-quality line diagrams and clinical illustrations to highlight key points in the text.

- Focuses on the evidence behind contact lens practice, enabling you to make informed choices about the care you give to your patients.

Trusted by 375,005 students

Access to over 1 million titles for a fair monthly price.

Study more efficiently using our study tools.

Information

Section 1

Contact Lens History and Material Development

1

The History of Contact Lenses*

Jacqueline Lamb, Tim Bowden †

Introduction

The development of contact lenses is long and complex, starting mainly in Germany and then moving across Europe to the USA before going international. The authors have tried to keep things chronological; however, these developments do not fall into a nice convenient timeline. As you read the chapter, remember that the original ‘contact lens pioneers’ had limited equipment and materials available. They were truly working in the dark, and advancements happened only as new materials and new technologies became available. There were no antibiotics, so contact lenses were fitted by ophthalmologists only when clinically necessary, for conical cornea (keratoconus), symblepharon and other corneal diseases. Due to the working relationships between ophthalmologists and other eye care professionals, fitting soon devolved to dispensing opticians (around 1912) and later extended to optometrists (around 1935). As knowledge of the physiology of the cornea developed and materials and designs improved, so too did their success – not always as straightforward as it might appear, as some developments have solved one problem simply to replace it with another! At the time of writing, end-of-day comfort is still an issue, with some practitioners limiting wearing time to little more than it used to be in the 1930s.

Early Theorists

1508: Leonardo da Vinci (Italy) It had previously been assumed that, in his Codex D, folio 3, famously illustrating a man with his head lowered into a large bowl of water, da Vinci showed the invention of a contact lens (Ferrero 1952, Hofstetter & Graham 1953, Gasson 1976). However, in the retranslation by Robert Heitz, it is clear that this was not a prototype contact lens but the beginning of understanding corneal neutralisation (Heitz 2003).

1637: René Descartes (France, Holland, Sweden) described in his seventh Discourse of La Dioptrique a fluid-filled tube used to enlarge the size of the retinal image (Enoch 1956).

1685: Philippe de la Hire (Paris, France), a mathematician, presented his dissertations on the neutralisation of the cornea in 1685 and 1694 and speculated that myopia was axial or refractive. Sadly, his theories about accommodation and entoptic phenomenon were considered so controversial that his views on optics were largely ignored (Duke-Elder 1970).

1801: Thomas Young (Somerset, England) studied medicine in London and Edinburgh and physics at Gottingen. He conducted research into the eye, identifying the cause of astigmatism, and published a three-colour theory of perception. As a fellow at Cambridge University, he carried out his classic experiment on accommodation using a water-filled lens which he placed on the eye to neutralise the refractive effect of the cornea (Young 1801).

1827: George Biddell Airy (England), inspired by Thomas Young and cooperating with John Herschel at Cambridge University, experimented with his own astigmatism. He described not only the optical theory of astigmatism but also its correction with a theoretical back surface toric lens (Airy 1827, Herschel 1845).

1845: Sir John F. W. Herschel (Slough, England) was the son of Sir William Herschel, discoverer of Uranus. In his dissertation Light, he described the optical correction of malformed and distorted corneas using convex lenses applied to the eye. He suggested correcting ‘very bad cases of irregular cornea’ by using ‘some transparent animal jelly contained in a spherical capsule of glass’ and then went on to suggest whether ‘an actual mould of the cornea might be taken and impressed on some transparent medium’ (Herschel 1845).

1846: Carl Zeiss (Jena, Germany), a mechanic who was 30 years of age at the time, opened a small workshop and store in Jena's Neugasse No. 7 to make scientific tools and instruments, telescopes and microscopes. This was the foundation of the company Zeiss (www.zeiss.com).

1851: Johann Nepomuk Czermak (Prague, Austro-German) developed a water-filled goggle strapped to the front of the eye to correct keratoconus, a device which he called the orthoscope. In 1896 Theodor Lohnstein developed a similar device, which he called the Hydrodiascope.

1854: Keratoconus. The first adequate description of keratoconus was published (John Nottingham, Great Britain).

1859: William White Cooper (London, England) was Queen Victoria's oculist. He had glass masks made by artificial-eye makers Gray and Holford of Goswell Road, London, to protect the eye in cases of symblepharon (Fig. 1.1). These were clear glass shells very like scleral lenses but with no optic zone over the cornea.

Fig. 1.1 Glass mask from Grey and Halford. (Reproduced from Contact Lenses: the Story, T Bowden.)

1882: Dr Xavier Galezowski (Franco-Polish) suggested using a gelatine disc applied to the cornea immediately after cataract extraction. The disc was impregnated with cocaine and sublimate of mercury to provide corneal anaesthesia to relieve postoperative pain and antiseptic cover to prevent infection (Mann 1938). Here we see not only the first use of a soft and hydrophilic contact appliance but also the forerunner of the hydrophilic lens as a dispenser of ophthalmic medication. Local anaesthesia in the form of cocaine drops was widely used by 1886. Initially adopted by Karl Koller in 1884, the anaesthesia's use in German ophthalmology became almost universal (www.rsm.ac.uk).

Scleral Lenses

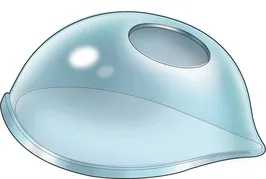

1887: Friedrich A. Müller and Albert C. Müller (Wiesbaden, Germany) were from a family of artificial-eye makers; they made and supplied a protective device for a patient of Dr Theodore Saemisch. The patient had surgical damage to the right eyelids leaving the cornea exposed, whilst sight in his left eye was impaired due to myopia and cataract. By making a glass shell, which encased but did not touch the cornea, the Müllers maintained fluid around the cornea, preventing its further desiccation. The protective shell looked like an artificial eye, although the cornea was left clear (Nissel 1965). The patient wrote a letter in 1908 (now lost) reporting that since 1887 he had worn the lens continuously, day and night, for 18 months to 2 years at a time (Müller & Müller 1910, Müller 1920, Mann 1973). In reality the lens needed to be replaced every 18 months to 2 years due to corrosion of the glass surface by the tears (Bowden 2009). The Müller brothers continued to produce thin, lightweight blown glass lenses with clear corneal regions and white scleral portions (Fig. 1.2), which were well tolerated. The optic portions were variable, and years later it was proposed that the excellent toleration of these glass lenses (and apparent avoidance of corneal oedema) was probably due to the characteristic aspheric shape of their scleral zones, producing loose channels for better tear flow and oxygen exchange.

Fig. 1.2 Blown glass Müller lens showing the transparent corneal and white scleral portions complete with blood vessels, circa 1900.

1888: Adolf Eugen Fick (Germany) was an ophthalmologist who, after returning from South Africa, began work in the ophthalmic clinic in Zurich under Professor Haab. He was interested in keratoconus and experimented with making corneal moulds and constructing glass shells for rabbits' eyes. He had glass scleral lenses made by Professor Abbe at Carl Zeiss in Jena for human cadaver eyes. The lenses had a back optic zone radius of 8 mm, optic zone diameter of 14 mm, a scleral band width of 3 mm, with a scleral zone radius of curvature of 15 mm. Fick described six patients on whom he had tried his lenses: One was keratoconic, and the other five had varying degrees of corneal opacity. In the keratoconic eye, he improved the vision from 2/60 to 6/36, but at the time he published, none of these patients was actually wearing the lenses for any length of time. He observed that:

- ▪ the radius of curvature of the cornea was stee...

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title Page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright

- Video Table of Contents

- Preface to the Sixth Edition

- Preface to the First Edition

- Contributors

- Glossary of Terms

- Section 1 Contact Lens History and Material Development

- Section 2 Anatomy, Physiology and Patient Suitability

- Section 3 Instrumentation and Lens Design

- Section 4 Lens Fitting Modalities

- Section 5 Patient Management and Aftercare

- Section 6 Specialist Lens Fitting

- Section 7 Other Aspects of Contact Lens Fitting

- Section 8 Additional Historical Background

- Section 9 Chapter Addendums: Supplementary Information

- Appendix

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Contact Lenses by Anthony J. Phillips,Lynne Speedwell in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Opthalmology & Optometry. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.