Introduction

Anaesthesia is one of the greatest ‘discoveries’ there has ever been – there are few scientific advances which have reduced pain and suffering in so many people and animals. It is difficult to remember that the first anaesthetic was administered only in the 1840s (there is argument as to who was first to administer it clinically), although analgesics (for example opiates) have been available for many centuries. The term anaesthesia was coined by Oliver Wendell Holmes in 1846 to describe using ether to produce insensibility in a single word and it comes from the Greek ‘without feeling’. The term ‘analgesia’ is Greek for ‘without pain’.

While anaesthesia has precisely the same meaning as when it was first coined, i.e. the state in which an animal is insensible to pain resulting from the trauma of surgery, it is now used much more widely. Starting with the premise that ‘pain is the conscious perception of a noxious stimulus’, two conditions may be envisaged: general anaesthesia where the animal is unconscious and apparently unaware of its surroundings, and analgesia or local anaesthesia where the animal, although seemingly aware of its surroundings, shows diminished or no perception of pain. Perioperative analgesia, a subject once much neglected by veterinarians, is now recognized as an essential component of the process, and the physiology of pain and mechanisms of how it can be controlled and treated are discussed in Chapter 5, Analgesia.

Veterinary anaesthesia

The clinical discipline of veterinary anaesthesia is essentially a practical subject based on science. In addition to the scientific base for human anaesthesia, the veterinarian has to contend with species differences, particularly in anatomy and in metabolism that effects the actions and elimination of drugs.

In clinical veterinary anaesthesia, the major requirements of the anaesthetist are:

•Humane treatment of the animal

▪This includes prevention of awareness of pain, relief of anxiety and sympathetic animal handling

•Provision of adequate conditions for the procedure

▪This includes adequate immobility and relaxation

▪Ensuring neither the animal, nor the personnel are injured in any way.

All patients require an adequate standard of monitoring (Chapter 2), and of general care throughout the anaesthetic process. However, other than this, there is a myriad of acceptable methods from which the anaesthetist can choose to satisfy the above aims. Certain drugs and/or systems may be put forward as ‘best practice’ but, in veterinary anaesthesia, there is rarely the ‘evidence base’ to prove that they are so. Choice of methods used may be limited by a number of factors. Legal requirements, which will depend on the country concerned, need to be observed. Examples include laws involving the control of dangerous drugs, or the choice of drugs in animals destined for human consumption. In the European Union, currently, the ‘cascade’ is a major barrier to anaesthetists' choice. This law implies that if there is a drug licensed for a species, it is criminal to use another unlicensed agent for the same purpose, unless the veterinary surgeon can prove that their alternative choice was justified for welfare of the specific individual animal concerned. Facilities may be limited, and while expense should not be the governing factor, it does need to be considered; animals throughout the world require anaesthesia and if the owners cannot afford the cost, the animal will be denied treatment. The objective of this book is to give the reader the information enabling them to make an informed choice of the best method of anaesthesia and care for their patient in their circumstances.

General anaesthesia

General anaesthesia is and has been given many different definitions (reviewed by Urban & Bleckwenn, 2002), but a simple practical one that has been used in the previous editions of this book is ‘the reversible controlled drug induced intoxication of the central nervous system (CNS) in which the patient neither perceives nor recalls noxious or painful stimuli’. Professors Rees and Grey (1950) introduced the concept that the requirements from general anaesthesia were analgesia, muscle relaxation and ‘narcosis’, these being known as the ‘Liverpool Triad’. This idea has been expanded to add suppression of reflexes (motor and autonomic) and unconsciousness or at least amnesia and, most importantly, that these requirements should be achieved without causing harm to the patient. For over 100 years anaesthesia was achieved mainly with a single drug, most commonly ether. Now, as well as a number of anaesthetic drugs which are administered by inhalation as is ether (see Chapter 7), single-agent drugs that are given by injection (see Chapter 6) are also employed. However, in clinical practice, it is now usual to use many different agents, which act at multiple receptors, in the CNS and peripherally, in order to achieve the goals required to provide good anaesthesia.

Currently, when considering single-agent anaesthetics, many authorities now believe that the state of general anaesthesia requires only two features: immobility in response to noxious stimulation and amnesia (the latter often taken as unconsciousness) (Eger et al., 1997; Urban & Bleckwenn, 2002). The argument is that the immobility is required for surgery; if the patient is unconscious they cannot perceive pain (although the autonomic system may still react to noxious stimuli), and if they don't remember the pain, it is similar to lack of perception. This theory ignores evidence and theories relating to pain and hypersensitization as described in Chapter 5. However, it considers that analgesia is desirable but is not an essential feature of the state of ‘general anaesthesia’. Thus the ‘definition’ of a single-agent anaesthetic drug, such as the injectable agent, propofol or the volatile anaesthetic agents is that they have these two actions of preventing movement and causing amnesia (Franks, 2006). Some compounds which from structure and lipophility might be expected to be anaesthetics can cause amnesia without immobility; these are sometimes termed ‘non-anaesthetics’ (Johansson & Zou, 2001), their major interest being related to studies of mechanism of anaesthetic action.

Mechanisms of action of general anaesthetic agents

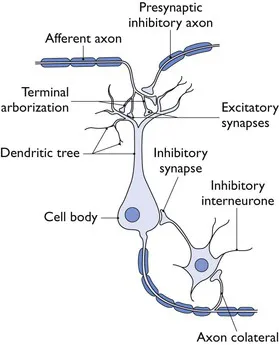

The central nervous system control of the functions altered by anaesthesia and related drugs is incredibly complex. Sherrington in 1906 pointed out the importance of the synapse in the CNS in providing connections between multiple neuronal systems (Fig. 1.1). At synapses, transmission involves release of transmitter that will ‘trigger’ the action of the next neuron. Receptors sensitive to the transmitter may be postsynaptic, or presynaptic feeding back on the original nerve terminal and modulating further action. Transmitters act through two main types of receptor: ionotropic and metabotropic. With inotropic or ‘ligand-gated’ receptors, the transmitter binds directly with the ion-channel proteins, allowing the channel to open and the ions to pass. Binding of a transmitter to metabotropic receptors involves G-proteins as secondary messengers. Recent roles for voltage-gated channels, where changes in cellular membrane potential triggers a response, such as two-pore potassium channels have also been identified.

Figure 1.1 Schematic diagram of the organization of a synaptic relay within the CNS.

In the CNS, three major transmitters are considered most directly relevant to general anaesthesia. Gamma-amino-butyric acid (GABA) is inhibitory and decreases the excitability of neurons. Glycine is inhibitory in most circumstances and is the most important inhibitory transmitter at the spinal cord. The main excitatory transmitter in the CNS is glutamate. Anaesthetic drugs that are thought to act at the N-methyl d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor, one of at least three types of ligand-gated glutamate receptor, inhibit the effect of glutamate, thus again inhibiting the CNS. However, there are many other relevant transmitters, for example acetylcholine, dopamine, norepinephrine, endogenous opioids and others (Sonner et al., 2003) and their resultant actions may influence (modulate) the actions, directly or indirectly, of the GABA, glycine and glutamate pathways.

In the 1900s, for the inhalation agents (no injectable had been discovered), Meyer and Overton independently noted the correlation between anaesthetic potency and solubility in oil, which led to the ‘lipid theory’ that general anaesthetics acted through a non-specific mechanism by changing the lipid bilayer of nerve cells. There are exceptions which disprove the hypothesis but, nevertheless, for most the correlation is amazing, and this theory, with modifications, held sway until Franks and Lieb (1984) showed that inhalational general anaesthetics inhibited protein activity in the absence of lipids. This finding led to the explosion of studies on (a) where in the CNS anaesthetics act, (b) differences between motor and amnesic actions and, finally, (c) the molecular targets for action. (Franks (2006) quotes a review that cites 30 possible such targets.) All these three points are inextricably interlinked. A full discussion is beyond the remit of this book, but the following very si...