Functional Movement Development Across the Life Span

- 374 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Functional Movement Development Across the Life Span

About this book

Providing a solid foundation in the normal development of functional movement, Functional Movement Development Across the Life Span, 3rd Edition helps you recognize and understand movement disorders and effectively manage patients with abnormal motor function. It begins with coverage of basic theory, motor development and motor control, and evaluation of function, then discusses the body systems contributing to functional movement, and defines functional movement outcomes in terms of age, vital functions, posture and balance, locomotion, prehension, and health and illness. This edition includes more clinical examples and applications, and updates data relating to typical performance on standardized tests of balance. Written by physical therapy experts Donna J. Cech and Suzanne "Tink" Martin, this book provides evidence-based information and tools you need to understand functional movement and manage patients' functional skills throughout the life span.- Over 200 illustrations, tables, and special features clarify developmental concepts, address clinical implications, and summarize key points relating to clinical practice.- A focus on evidence-based information covers development changes across the life span and how they impact function.- A logical, easy-to-read format includes 15 chapters organized into three units covering basics, body systems, and age-related functional outcomes respectively.- Expanded integration of ICF (International Classification of Function) aligns learning and critical thinking with current health care models.- Additional clinical examples help you apply developmental information to clinical practice.- Expanded content on assessment of function now includes discussion of participation level standardized assessments and assessments of quality-of-life scales.- More concise information on the normal anatomy and physiology of each body system allows a sharper focus on development changes across the lifespan and how they impact function.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

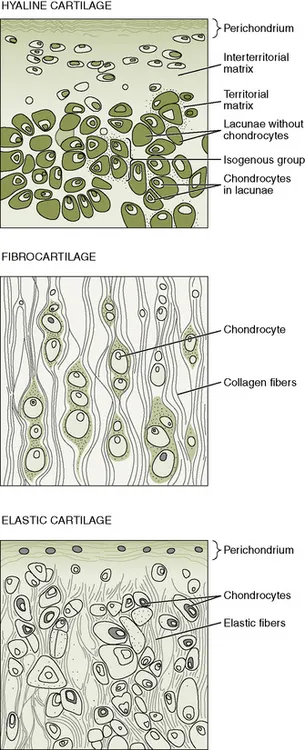

Components of the skeletal system

Cartilage

Properties

Formation

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Front matter

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contributors

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Table of Contents

- Unit One: Definition of Functional Movement

- Unit Two: Body Systems Contributing to Functional Movement

- Unit Three: Functional Movement Outcomes

- Index

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app