- 708 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Surgery of the Thyroid and Parathyroid Glands E-Book

About this book

Bringing together more than over 120 expert contributors from otolaryngology, general surgery, endocrinology, and pathology, Surgery of the Thyroid and Parathyroid Glands, 3rd Edition, presents an interdisciplinary approach to surgical management and treatment of benign and malignant disease. This renowned text/atlas is an ideal resource at all levels of surgical experience: for residents and junior surgeons, it clearly provides all relevant anatomy, surgical procedures, and workup; for experienced surgeons, it details the management of difficult cases, including revision surgery. Highly illustrated and accompanied by dozens of videos, this edition brings you up to date with the full continuum of care in thyroid and parathyroid surgery.- Easy-to-follow, templated chapters cover preoperative evaluation, surgical anatomy, intraoperative techniques, and postoperative management, for a full range of disorders of the thyroid and parathyroid glands.- More than 30 procedural videos walk you step by step through minimally invasive thyroid surgery, surgical anatomy and monitoring of the recurrent laryngeal nerve, surgery for locally advanced thyroid cancer and nodal disease, and more; plus 23 chapter guide videos from the authors with Surgical Text Video Editor-in-Chief Gregory W. Randolph, Jr.- Coverage of cutting-edge topics includes recurrent laryngeal nerve monitoring, minimally invasive surgery and the role of PET in staging and surgical planning.- Expert guidance on thyroid cancer, including multiple chapters on PTC, MTC and HCC, ATC and NIFTP.- New chapters cover medical oncology and TKI therapy.- Extensive coverage of key topics such as FNA mutational analysis, transoral and minimally invasive surgery, recurrent laryngeal nerve monitoring, management of RLN paralysis, all aspects of parathyroid disease, ethics, malpractice, and more.- Enhanced eBook version included with purchase. Your enhanced eBook allows you to access all of the text, figures, and references from the book on a variety of devices.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Introduction

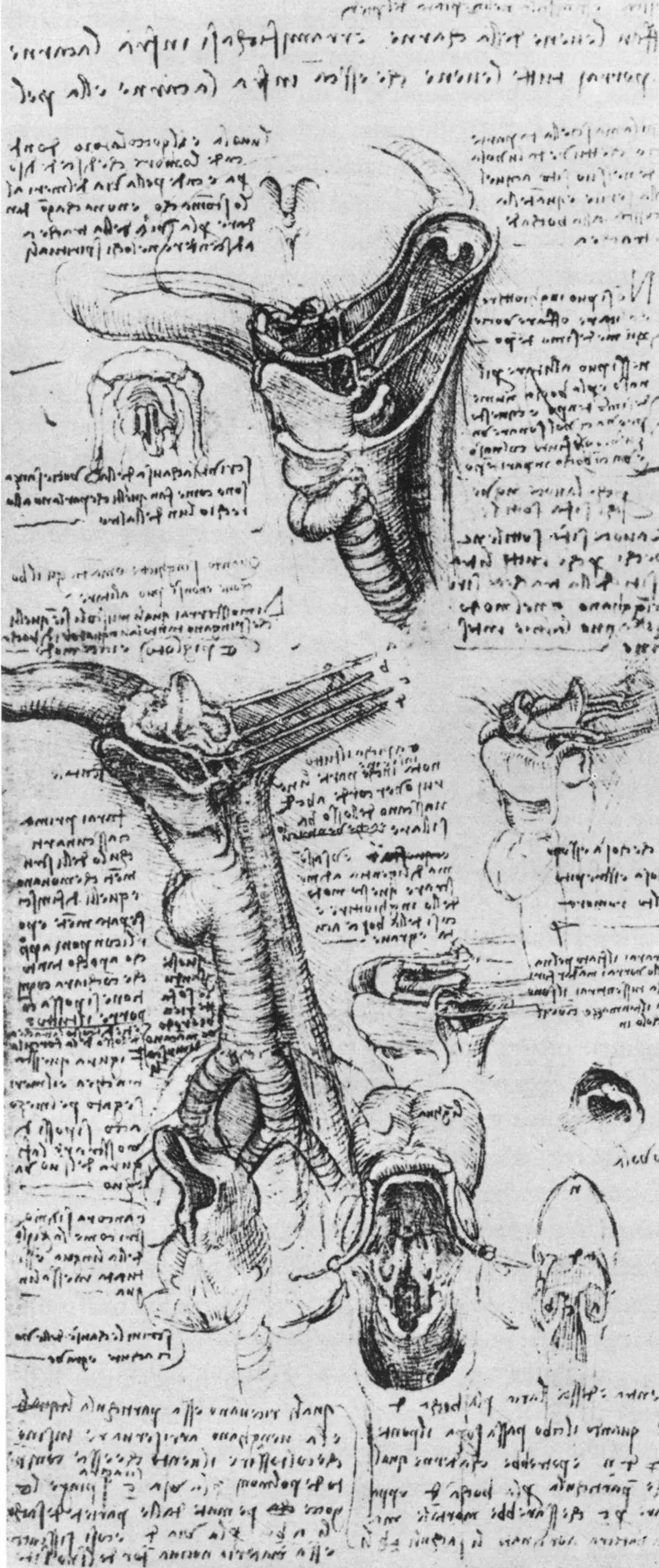

History of Thyroid and Parathyroid Surgery

The early years

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contributors

- Foreword to the Second Edition

- Foreword

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Video Contents

- Half Title

- Section 1: Introduction

- Section 2: Benign Thyroid Disease

- Section 3: Preoperative Evaluation

- Section 4: Thyroid Neoplasia

- Section 5: Thyroid and Neck Surgery

- Section 6: Postoperative Considerations

- Section 7: Postoperative Management

- Section 8: Parathyroid Surgery

- Index