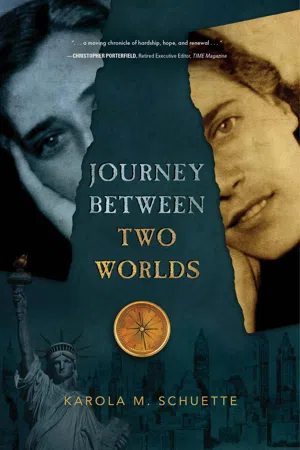

![]()

CHAPTER 1

My Inspiration

I WOULD NOT HAVE MUCH of a story to tell if it were not for the arrival in Germany of a German-born American soldier named William Hermann Schuette. Up until then I did not feel my life had been of interest to anybody. World War II, with all its tyranny, had come to an end but destruction, desolation, and hunger, combined with hopelessness, was all around. In early October 1946, William Schuette entered the scene.

He wrote this account in his diary:

In the spring of 1946, I looked forward with anxiety to being discharged from the army, not because I had any complaints about my work or conditions, but rather the desire for a change. My work in the service was highly educational and interesting to me. The great majority of the boys were quite intellectual and generally good company and the recreational facilities unlimited. I shall never forget the wonderful times I had in Washington, DC on the Potomac River and at Jiggs. I left the army on April 28. At that time, I had an agreement with the Contingency Program Management Office to work in Frankfurt, Germany for Colonel Wentworth within three weeks. Due to circumstances this fell through; several weeks passed, however, before I found out about it. During the five summer months of leisure, I did paintings, read the classics, played accordion, cards, and chess; most days were spent on the beach. I was very happy to hear I was to leave the States on September 26 aboard the SS George Washington for Bremerhaven, Germany to accept a job at the Civil Censorship Division (CCD) in Frankfurt, Germany. This was an opportunity to see Germany again and at the same time save a little money while employed as a War Department Employee (WDE) in the American occupied zone.

The voyage was very pleasant, lively, and educational for me. I understand that the SS George Washington as an army transport ship could carry as many as 6,000 men, whereas we were only 1,000. Arriving in Bremerhaven on October 6, nothing much of interest was to be seen until we boarded the train for Frankfurt the following day. Passing through the cities of Hannover and Kassel one could see the devastation along the journey and notice the frail, bewildered condition of the people. US vehicles and men in uniform (occupational forces) were at all important points. My biggest surprise came when I saw Frankfurt. Here it seemed that every building was damaged in one way or another. The rare undamaged ones provided lodging for Allied personnel. Where the hundreds of thousands of people actually lived, I didn’t know. Strangely enough, instead of sympathizing with these poor, ragged, and hungry individuals, one became hardened and indifferent to all the misery. I felt a little uneasy at this point of my life being back in Germany, now destroyed beyond recognition, and wondered what the village of my birth may at this time look like and what the people there must have suffered. Eventually I would see for myself.

Doing a quick survey of the type of work I was about to undertake, I found that some of it was more or less negligible. There we were in CCD checking everyone and anything that a German writes or talks about, and even arresting quite a number of CIC (Civilian Identity Certification), whom we in this branch still considered dangerous. The general atmosphere was tense, and suspicion constantly kept one on guard. No one knew who was enemy, spy, or to be trusted. On a daily basis I was transported from my living quarters (a shared apartment with other WDEs) in a compound in the town of Offenbach to Frankfurt, where my actual assignment was to censor telegrams and phone calls going in and out of the American occupied zone.

William Schuette, Army Intelligence officer

The Offenbach compound had within its confines our living quarters, a mess hall, and a PX (post exchange), where all personnel could buy their rations and other available goods not accessible anywhere else. The compound was fenced in by high security fences, had guards at all points, and included the motor pool. Below, in the basement, were long tables where German men and women (carefully screened for their character and aptitude and sworn to maintain absolute secrecy about their work) opened, read, censored, and then sealed again all mail leaving the occupied zone. They also went through the very same process with incoming mail from the other occupied zones within Germany, so the recipient in many cases could ultimately not make sense of the letter’s censored contents. Everyone had to be checked entering or leaving the compound. The Germans not only had to show their identification but also wear yellow buttons. Any sign of suspicious appearance caused a body search; all kinds of food were the most common items smuggled.

There was also an office called Special Services where one could buy the military publication Stars and Stripes, rent a bike that was shipped over from the States, and get a ticket to a movie, the theater or Saturday night dance. The latter, which were held in makeshift or hurriedly repaired quarters, were provided as a welcome distraction to get away from the depressing daily picture: ruined landscapes, buildings, and the general spy atmosphere on the outside.

In this Special Services office worked a young woman whom I immediately took great interest in and found very attractive. But with my work schedule I did not find a chance to even talk to her, other than office talk, since she was also constantly observed by supervisors so as not to get personal or friendly with anyone. But I knew then and there already that I would ask to come to her house sometime and hoped this would be soon. She would not get out of my mind. Maybe I could ask to visit for a holiday. I felt a great love for her and knew for sure we would be married.

circa 1942 Karola

In the next visit to the Special Services office (under the guise of wanting to buy a theater ticket), I wished to find out more about her and, under some official excuse, said I needed to see her building pass. I had guessed her age to be about nineteen and could hardly believe that she was to be twenty-four on December 29 that year. I was hoping somehow to wangle an invitation for Christmas, just to get things going, but it took another long week before I finally was invited to her place for Christmas Eve.

Here I have to take over from Bill with my own recollections.

I had come to work in this Civil Censorship Division via a long employment preparation. After finishing eight years of school at age fourteen, I became a legal secretary-apprentice at a lawyer’s office for the summer of 1937, attending evening courses in stenography, typing, and bookkeeping. The lawyer was transferred out of Offenbach to someplace near the Rhein, which made my three-year learning contract null and void. However, he was able to find me another firm in the same building, where I continued my contract until an appropriate office was secured for me to accomplish my legal secretary training. Bill collection firm Bien was sort of slave labor for me. I had to be there by seven o’clock, an hour before anyone else, and my duties included cleaning the potbelly stove, carrying out the ashes to the garbage, starting a new fire, and fetching water for a hot beverage to accommodate the other four employees and owners. In addition, dusting the office was a necessity, along with sharpening pencils and putting new ribbons in the outdated typewriters. By this time the place was beginning to warm up. I needed to wash my dirty hands and put on a white office coat to set myself apart as the underling apprentice. In one way the coat came in handy. It covered up my totally poor wardrobe. Then, around nine, everybody would give a list of what they wanted to eat for breakfast. It always meant a trip to the bakery for warm Broetchen (rolls), then to the butcher for hot breakfast sausage, fresh from a steaming kettle. Everyone, of course, wanted something different. One could say I served my apprenticeship in office management and breakfast assembling technology before I was even allowed to sit at a typewriter to type up warning letters to people with overdue bills. There was the starter, appropriately called the Number One letter, and then they went all the way to fire-alarm-police-whistle-sharp Number Ten! What happened after the tenth letter? I was not allowed to find out, and in any case, I had been sworn to secrecy.

After a few months with the Bien firm, I could at last continue my apprenticeship with a genuine established lawyer, a wonderful person named Dr. Goebel. Now my real training began. I was still doing the breakfast run, but everything was on a much more refined level. I did filing, brought my employer’s robe to the courthouse, and often was trusted to deliver a client’s file. Finally came the big moments of taking shorthand and typing the letters or court files myself. Many of those called for carbon copies, sometimes as many as five or six. The tragedy was in making a typing error. To erase the mistake one could only erase the top page after a tiny piece of paper was carefully inserted underneath each carbon paper on the very spot, a most time-consuming and irritating process. The copies that were on much thinner paper would usually reveal a smudge, no matter how carefully they were corrected. Such was the beginner’s lot.

During the years preceding my first taste of employment, while I was still a student, Hitler had become the new messiah for his party. Bit by bit he had charmed Germany’s youth into his ideology and created job opportunities for those suffering unemployment. Among them was my father, who had been unemployed for as long as I could remember. Finally, he got a job applying his training as a Maschinenschlosser (machinist), and simultaneously I was hired into apprenticeship as a future legal secretary. My mother could not believe that after all the miserable years of stretching one Deutsche Mark for a day, we could eat more nourishing food, as well as buy much needed new linen. It was like Christmas, until my father came home from his first day of work, quite shattered about the kinds of things that were now being built. The firm of Hartmann, known as a reputable manufacturer, was now making parts for the war machine, as my father would say. Hitler was beginning to rattle his saber; therefore, it wouldn’t be long before that machinery was put to use. What a sobering, scary discovery this was for him. We paid attention to my father’s words, although he was known as quite a pessimist. We did pay attention. Since the Hitler party by now had most everything in its vise-like grip, one had to stand at attention, salute at attention, and practically never lose attention. Every official or business letter had to be signed with Heil Hitler. Beware of forgetting this requirement, or you were put under surveillance. Beware, beware. You are suspect.

I have to mention these things because they tied in with every aspect of existence: your daily life, your religious beliefs, your relationship with friends and family, every detail of your waking hours. It culminated in not trusting your own self in your sleep. A neighbor might hear something, denounce you to the authorities to make points with the party, and have you deported to a labor camp. Even in school religious instruction with a Protestant minister and a Catholic priest, each teaching two hours a week, was eliminated and replaced with sports. All of a sudden, our Jewish friends did not attend public school anymore. The word was they were being taught in the synagogue. Slowly it became obvious one could no longer patronize Jewish stores. They were taken over by Aryan establishments. We were constantly under scrutiny because of our Jewish sounding name of Friedmann, and we had to produce umpteen documents verifying our ancestry. The age of persecution had begun. The meaning of trust, friendship, and caring about, or for, another...