- 368 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About this book

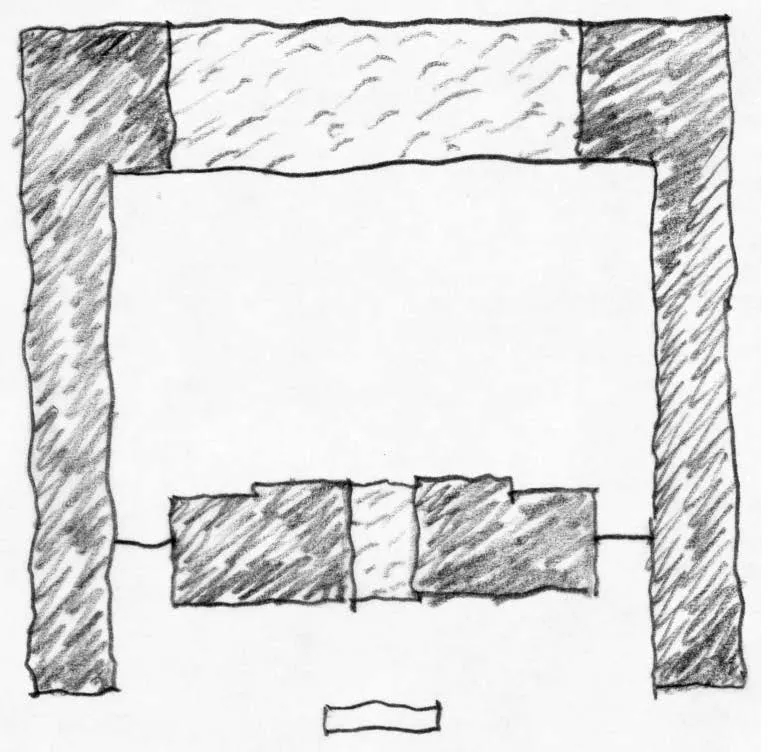

For more than three thousand years, Chinese life – from the city and the imperial palace, to the temple, the market and the family home – was configured around the courtyard. So too were the accomplishments of China's artistic, philosophical and institutional classes. Confucius' Courtyard tells the story of how the courtyard – that most singular and persistent architectural form – holds the key to understanding, even today, much of Chinese society and culture. Part architectural history, and part introduction to the cultural and philosophical history of China, the book explores the Chinese view of the world, and reveals the extent to which this is inextricably intertwined with the ancient concept of the courtyard, a place and a way of life which, it appears, has been almost entirely overlooked in China since the middle of the 20th century, and in the West for centuries. Along the way, it provides an accessible introduction to the Confucian idea of zhongyong ('the Middle Way'), the Chinese moral universe and the virtuous good life in the absence of an awesome God, and shows how these can only be fully understood through the humble courtyard – a space which is grounded in the earth, yet open to the heavens. Erudite, elegant and illustrated throughout by the author's own architectural drawings and sketches, Confucius' Courtyard weaves together architecture, philosophy and cultural history to explore what lies at the very heart of Chinese civilization.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Part One

Heaven

A Panacea from the Courtyard

1

What Makes the Chinese House

The conceptual parti

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half-Title Page

- About the Author

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Prologue

- Part One Heaven A Panacea from the Courtyard

- 1 What Makes the Chinese House

- 2 Heaven and What Is Below

- Part Two Heaven and Earth Equilibrium in the Courtyard

- 3 The Divergent Tower

- 4 Secluded World and Floating Life

- 5 A Deceiving Symbol

- 6 Literary Enchantment and the Garden House

- 7 The Golden Mean Finely Tuned

- 8 Living like ‘the Chinese’

- Part Three Earth The Emancipation of Desire and the Loss of Courtyard

- 9 The Irresistible Metropolis

- 10 The Assault of Modernity

- Epilogue: The Four or the Five

- Notes

- Index

- Copyright