- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Leading gender and science scholar Sarah S. Richardson charts the untold history of the idea that a woman's health and behavior during pregnancy can have long-term effects on her descendants' health and welfare.

The idea that a woman may leave a biological trace on her gestating offspring has long been a commonplace folk intuition and a matter of scientific intrigue, but the form of that idea has changed dramatically over time. Beginning with the advent of modern genetics at the turn of the twentieth century, biomedical scientists dismissed any notion that a mother—except in cases of extreme deprivation or injury—could alter her offspring's traits. Consensus asserted that a child's fate was set by a combination of its genes and post-birth upbringing.

Over the last fifty years, however, this consensus was dismantled, and today, research on the intrauterine environment and its effects on the fetus is emerging as a robust program of study in medicine, public health, psychology, evolutionary biology, and genomics. Collectively, these sciences argue that a woman's experiences, behaviors, and physiology can have life-altering effects on offspring development.

Tracing a genealogy of ideas about heredity and maternal-fetal effects, this book offers a critical analysis of conceptual and ethical issues—in particular, the staggering implications for maternal well-being and reproductive autonomy—provoked by the striking rise of epigenetics and fetal origins science in postgenomic biology today.

The idea that a woman may leave a biological trace on her gestating offspring has long been a commonplace folk intuition and a matter of scientific intrigue, but the form of that idea has changed dramatically over time. Beginning with the advent of modern genetics at the turn of the twentieth century, biomedical scientists dismissed any notion that a mother—except in cases of extreme deprivation or injury—could alter her offspring's traits. Consensus asserted that a child's fate was set by a combination of its genes and post-birth upbringing.

Over the last fifty years, however, this consensus was dismantled, and today, research on the intrauterine environment and its effects on the fetus is emerging as a robust program of study in medicine, public health, psychology, evolutionary biology, and genomics. Collectively, these sciences argue that a woman's experiences, behaviors, and physiology can have life-altering effects on offspring development.

Tracing a genealogy of ideas about heredity and maternal-fetal effects, this book offers a critical analysis of conceptual and ethical issues—in particular, the staggering implications for maternal well-being and reproductive autonomy—provoked by the striking rise of epigenetics and fetal origins science in postgenomic biology today.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Maternal Imprint by Sarah S. Richardson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Gynecology, Obstetrics & Midwifery. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

University of Chicago PressYear

2021Print ISBN

9780226544809, 9780226544779eBook ISBN

9780226807072Chapter 1

Introduction: The Maternal Imprint

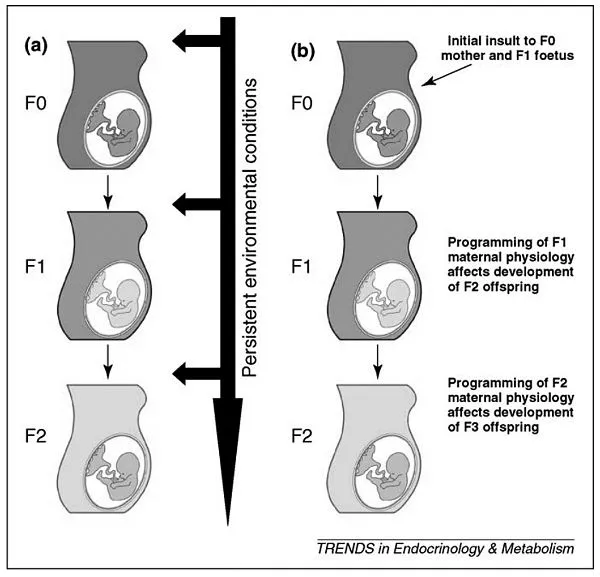

This book is about the bewitching idea that the environment in which you are gestated leaves a permanent imprint on you and your future descendants. I first became intrigued by this idea a decade ago, when I encountered neuroscientist Rachel Yehuda’s studies of intergenerational Holocaust trauma in the families of Jewish survivors. Children of Holocaust survivors experience higher rates of vulnerability to trauma themselves, and Yehuda believes that this is because they were gestated in an environment with high cortisol, a hormone critical in stress regulation. This intrauterine experience, she contends, permanently modified survivors’ children’s genome regulation so that as adults they are more vulnerable to psychiatric disorders when they experience stress or trauma. Their offspring, whose own gametes are developing while in the womb, might transmit these modifications to their own grandchildren, refracting the experience of trauma across generations (fig. 1.1).1

FIGURE 1.1 Mechanisms for the intergenerational transmission of programming effects. (a) Persistence of an adverse external environment can result in the reproduction of the phenotype in multiple generations. (b) The induction of programmed effects in the F1 offspring following in utero exposure (e.g. programmed changes in maternal physiology or size) results in programmed effects on the developing F2 fetus and so on. From Drake and Liu, “Intergenerational Transmission of Programmed Effects: Public Health Consequences.” By permission of Elsevier.

Poet-novelist Elizabeth Rosner, a daughter of Holocaust survivors, wove Yehuda’s findings into an extended reflection on intergenerational trauma in her 2017 book Survivor Cafe: The Legacy of Trauma and the Labyrinth of Memory. Research on how the fetal environment programs our genomes, Rosner suggested, “is bringing us empirical proof of a legacy we have already known in our bones, our dreams, and our terrors. . . . Which is to say, my generation’s DNA carries the expression of our parents’ trauma, and the trauma of our grandparents too. Our own biochemistry and neurology have been affected by what they endured.”2

As the matrilineal granddaughter of a Holocaust survivor just beginning my own family, I could not help but be curious about these claims. As a historian and philosopher of science who specializes in gender, genetics, and the social dimensions of scientific knowledge, the implications, both scientific and cultural, of the idea that a woman’s health, behavior, and milieu can have intergenerational effects proved equally irresistible.

THE RISE OF FETAL ORIGINS SCIENCE

Soon, I realized that Yehuda’s research was part of an efflorescence, in recent years, of scientific interest in the long-term effects of the intrauterine environment. Beyond psychiatric disorders, scientists in a wide-ranging field of research on the fetal origins of health and life outcomes are searching for links between maternal factors such as diet, stress, and environmental exposures and offspring outcomes such as obesity, heart disease, autism, asthma, sexual orientation, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and intelligence.3

While scientific interest in the imprint left by the womb has a long history, the proximate foundations of the modern-day field of fetal origins science—sometimes called Developmental Origins of Health and Disease, or DOHaD—trace to the late 1980s. Using historical health records from the poorest areas of England, in 1989 British epidemiologist David Barker demonstrated that communities with the highest infant mortality rates in the 1930s had the highest heart disease mortality rates 50 years later. Barker argued that the risk of heart disease in these populations was linked to development in the womb and hence could be seen as an outcome of the poor health status of their mothers, not only during the pregnancy itself, but throughout their own lives.4 At the time, Barker’s claims encountered disbelief and resistance. But today, three decades later, this hypothesis drives multiple lines of inquiry at the intersection of developmental biology, teratology, nutrition science, environmental science, and lifecourse epidemiology.5 As of 2014, this research had proliferated considerably: more than 130,000 papers on fetal programming of disease were available in the biomedical research database PubMed.6

Compared to speculations on maternal intrauterine effects in previous eras, today’s maternal-fetal effects science benefits from a greatly expanded body of epidemiological data on the prenatal period. Beginning in the late 1980s, researchers initiated large-scale prospective cohort studies tracking mothers and their offspring from pregnancy onwards. Interest in prenatal influences rose alongside two developments in the 1980s and 1990s. The first was the dramatic expansion of global public health investment in maternal and infant health. Policy makers, economists, and global development experts were increasingly highlighting the importance of the very early years for an individual’s long-term health and economic well-being. Improving outcomes at birth became widely seen as a central site of intervention for advancing economic development in the world’s poorest regions.7 Contemporary with this was a dramatic upswing in public and private investment in the biosciences associated with the Human Genome Project. Powerful new prenatal genetic testing technologies introduced the prospect of predicting health risks from the earliest stages of fetal development. Researchers argued for the need to pair the study of these genetic vulnerabilities with research on prenatal environmental effects, not only to better understand the interaction between the two, but also to advance a parallel knowledge base on the links between early developmental exposures and later patterns of health and disease.

The Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC) at Bristol University in the United Kingdom, emblemizes these developments. The study began in 1991, enrolling 13,761 pregnant women. Today it is one of the largest studies attempting to track the long-term effects of prenatal exposures. ALSPAC has collected copious biological samples from its children and mothers, including maternal blood and urine during pregnancy and cord blood and placental tissues at birth. To date, the study has amassed data on children at 68 time points, including 9 clinical assessments. Even the children’s baby teeth reside in the study’s databank, collected by ALSPAC’s appointed “tooth fairy.” ALSPAC data have yielded more than 2,000 scientific publications, including findings on risk factors for obesity, eczema, and asthma.8

In the mid-1990s, joining the excitement generated by the major genome sequencing projects, ALSPAC collected DNA from 11,000 children and 10,000 mothers in the study. Now, ALSPAC is introducing epigenetic methods. Epigenetics refers to molecular changes in the non-DNA regulatory apparatus of the genome. Epigenetic markers that help determine whether a particular site on the genome is active or silent can change in response to environmental stimuli. If these changes can be shown to be able to be induced by the intrauterine environment, to remain stable over time once induced, and to have functional implications for human health and biology, epigenetics may offer a causal mechanism explaining the long-term effects of maternal pregnancy effects posited in DOHaD (pronounced “dough-had”) studies.

But DOHaD science is not just mountains of data correlating prenatal exposures with later outcomes. Today’s research on maternal intrauterine effects combines this new trove of data with a set of guiding assumptions that serve as a conceptual framework for interpreting these data and launching research hypotheses.

MATERNAL EFFECTS AND THE BIOSOCIAL BODY

DOHaD researchers believe that human developmental plasticity is greatest during the critical period of intrauterine growth, and that prenatal cues from the maternal environment can permanently program the developing fetus in ways that alter physiological functioning as an adult. One hypothesis is that the sensitivity of human fetuses to their maternal environment is an evolutionary adaptation, allowing fetuses to attune themselves to their expected postnatal environment. But if metabolic and stress signals from the mother’s body do not match the actual world the fetus encounters—as in the case of a nutritionally deprived fetus entering a calorie-rich American dietary landscape—illness results. DOHaD founder David Barker influentially and provocatively appealed to this hypothesis to argue that many so-called Western diseases of affluence, such as breast cancer and heart disease, were driven by the rapid shift from the relative deprivation of early twentieth-century lifestyles to the hygienically and nutritionally transformed environment of the late twentieth century. An important prediction of this hypothesis is that because aspects of the intrauterine environment that a woman provides are themselves set by her own development in the womb, a “mismatch” between fetal programming and postnatal environment may “take several generations to disappear,” as Barker has claimed.9

Many DOHaD researchers believe that, in this way, intrauterine effects help explain how persistent social inequalities become embodied and pass across generations. University College London pediatrician and child nutrition expert Jonathan Wells, author of The Metabolic Ghetto (2016), argues that rising rates of metabolic disorders and obesity are bodily manifestations of the intergenerational transmission of health inequalities. Wells believes that features of the mother’s social and environmental context during her own development—including social class—are, in a sense, transmitted to the growing fetus, conditioning it for a life of inequality even before birth. “If pregnancy is a niche occupied by the fetus,” Wells has written, “then economic marginalization over generations can transform that niche into a physiological ghetto where the phenotypic consequences are long-term and liable to reproduction in future generations.”10

Similarly, Northwestern University anthropologist Chris Kuzawa hypothesizes that maternal hormones and nutrients provide the fetus “access to a cue that is predictive of its future nutritional environment.”11 He suggests that maternal signals to the fetus function “inertially” to prevent changes in the offspring that are too great and too rapid in a single generation. “The flow of nutrients reaching the fetus,” Kuzawa believes, “provides an integrated signal of nutrition as experienced by recent matrilineal ancestors, which effectively limits the responsiveness to short-term ecologic fluctuations during any given pregnancy.”12 Kuzawa likens this to a ‘‘crystal ball” that “allows the fetus to predict the future by seeing the past, as integrated by the soma of the matriline.”13 Problems can arise, however, when this fetal environment for developmental modification and “fine tuning” is either “impaired” or mismatched with current environmental conditions.14

Applying this conceptual framework, Kuzawa and Elizabeth Sweet argued in a 2009 article that maternal effects may help explain persistent racial disparities in rates of cardiovascular disease in the United States.15 Historically, African American women have experienced high rates of stress during pregnancy, in part due to experiences of slavery and its legacies of racism. This has contributed to lower birth weights, a predictor of later cardiovascular disease risk for offspring. Since a woman’s own birth weight predicts her child’s, maternal pregnancy effects provide a mechanism for the persistence of high cardiovascular disease rates across generations even after the diminishment of continued psychosocial or nutritional stressors. In this biosocial explanation of health disparities invoking maternal effects, racial differences are understood as social in origin, but mediated and transmitted by biological processes of early growth and development.

The science of “maternal effects”—defined by evolutionary geneticists Jason Wolf and Michael Wade as “the causal influence of the maternal genotype or phenotype on the offspring phenotype . . . generally through the maternally provided ‘environment’”—offers a picture of heredity different than the one we learned in high school genetics.16 It suggests that mothers endow the fetus with more than just DNA. As they develop, infants are programmed by maternal factors that influence the environment in which they grow. To many, research on maternal intrauterine effects shows just how profoundly our bodies are mediated by our environments, starting at conception. Applied to questions of persistent patterns of social inequality and to the phenomenon of intergenerational inheritance of trauma in human populations, maternal effects science offers a potentially powerful approach to understanding how our bodies are at once biological and social.

I am of two minds about such claims. Intuitively, I believe that bodies register their social and physical environments in ways subtle and profound, that health is a matter not just of biochemistry but also of social chemistry, and that the maternal-fetal relation is a powerful and mysterious one. Today, maternal effects science is part of a broader and, from my perspective, welcome turn away from gene-centric models of the determinants of health and human biological variation. The science of maternal effects suggests greater enigma and complexity in heredity than a simplistic genetic story will tell.17

But as intellectually exciting and socially important as it is to appreciate bodies and biologies as shaped by their environments, the present intensive focus on a narrow window of human development—gestation—and on a particular class of bodies—those presenting as women of reproductive age—requires scrutiny. Situating the intrauterine environment as a critically determinative one for a range of life outcomes articulates social alarm through gestational reproductive bodies in ways that carry real implications for restrictions on reproductive autonomy. Moreover, even if intrauterine effects exist, an exaggerated focus on the mother as the bearer of reproductive risk may misdirect resources from other, more important contributors to health and life outcomes.

Maternal effects science is also an area where the intellectual excitement runs ahead of actual empirical findings. Despite—or perhaps due to—the fact that today, scientists have more precise tools than ever for studying the biochemical relation between a mother and fetus, and access to massive, multidimensional sets of human biological and social data across the life course, the science of maternal effects involves connecting unstable biological markers to small effects. In maternal effects research, the effects under examination are often what I have come to term “cryptic”: they are small, vary depending on ecosocial context, and frequently occur at a great temporal distance from the initial exposure, making causality challenging to establish.

CRYPTIC CAUSALITY

The crypticity of the effects studied in today’s fetal programming science is particularly brought into relief when compared with an earlier clas...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- 1 / Introduction: The Maternal Imprint

- 2 / Sex Equality in Heredity

- 3 / Prenatal Culture

- 4 / Germ Plasm Hygiene

- 5 / Maternal Effects

- 6 / Race, Birth Weight, and the Biosocial Body

- 7 / Fetal Programming

- 8 / It’s the Mother!

- 9 / Epilogue: Gender and Heredity in the Postgenomic Moment

- Acknowledgments

- Notes

- References

- Index