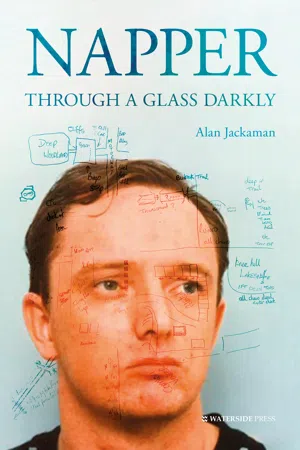

Introduction

This book was written to record for history the tragic circumstances which led to one man committing a sequence of vicious sexual assaults through to the murders of Rachel Nickell and Samantha and Jazmine Bisset. It has taken Alan Jackaman over 25 years to come to terms with what happened and he is now ready to relate his part in the downfall and imprisonment of Robert Napper.

The book, which contains a good deal of information not until now in the public domain, encompasses many intriguing aspects of the police investigations. In addition to a straightforward account of the solving of a heinous and complex series of crimes, it delves into media fascination with serious crime and demonstrates how the press may “latch on” to one murder whilst ignoring another, even more horrific one. It questions the strategic reasoning behind how the hierarchy of the police can be influenced by the intensity of media pressure as seen in the imbalance of financial support between the high profile Nickell investigation on Wimbledon Common and less public, more locally reported, Bisset enquiry.

The underlying reasons why Robert Napper became the psychotic killer he did are examined, from his troubled childhood to minor offending, progressing to serious sexual assaults, rapes and culminating in three brutal murders. It also looks at the emergence of modern criminal profiling in police investigations and its shortcomings.

The author has the benefit of having been appointed as an investigator on the Bisset case from the day of the murder through to seeing the case linked first to the Green Chain Walk series of rapes and (following Napper’s conviction for the Bisset murders), the unearthing of evidence to prove that the same man also killed Rachel Nickell.

Like the Bisset case in Plumstead, south east London, the murder of Rachel in south west London had become a “sticker”, following the early but misguided arrest and public vilification of the wrong man, Colin Stagg, an enticingly convenient “oddball” (who ultimately secured substantial damages against the Metropolitan Police Service). Until Alan’s team of detectives became insistent, no-one had connected the two sets of tragic events or linked them to the Green Chain Walk rapes and, as the book shows, sheer persistence is what at times kept that possible connection alive. The book shows how Alan Jackaman’s (and his colleagues’) determination ensured this even when faced with the disbelief of other officers and taunts such as, “It was Napper wot done it.” But Alan’s deep concern for Samantha, Jazmine and their family together with the terrible circumstances of their deaths and similarities with the Nickell case just would not allow him to let go.

Unusually, the story is laid out from the point of view of an officer of junior rank. Alan was simply a detective constable until given the (initially) temporary rank of detective sergeant for the purposes of the Bisset investigation. As a result, he is perhaps less inhibited than some higher in the police hierarchy when describing the problems which arise from “investigating on the cheap” or telling of the dramatic twists and turns of what seemed, in the Bisset case, to be the killing of an obscure mother and child in an unfashionable district of London. In contrast, the Nickell case, in the full glare of publicity, attracted major funding and the application of innovative (though what proved to be questionable) investigative techniques. The pressures on all three teams were enormous but the Bisset case and Green Chain Walk rapes were always poor cousins of the media-obsessed Wimbledon case.

The book follows the murder and rape cases from the start of each to the solving of a series of the twentieth century’s most notorious crimes and conviction of one of the UK’s most dangerous ever killers. It also looks into the dark mind of Robert Napper, his bizarre behaviour, delusions, family history, strange “doodles” and the sheer “luck” that allowed him to remain free to continue his offending for so long.

Chapter 1

“Take him down!”

Alan walked out of St Paul’s underground and turned left toward the Central Criminal Court, more popularly known as the Old Bailey. The December weather was cool but clear, the date the 18th December 2008. He felt empty-handed with no court papers to carry, no briefcase, a feeling as if he had forgotten something stayed with him as he strode at an even pace. There was no hurry, the appearance time in court was set for 10.30 am and, he was, as usual, too early.

The vast edifice of St Paul’s Cathedral loomed on the opposite side of the road, although there were the usual throngs of people on the street the vast rush to work was well past. He felt calm, today the fear was absent of not knowing what to expect in the cockpit of the criminal court, no queasy feeling in the pit of his stomach, only a sense of an ending.

Turning left into Old Bailey, so called because it once formed the fortified boundary walls of the old city, he could see the press were ahead of him, already gathering at the main entrance to the court, their cameras at the ready, reporters voicing their preliminary openings into hungry lenses. He walked past the jostling film crews, unrecognised, towards the familiar entrance. Things here had changed considerably since the last time this particular case had caused his presence to be summoned to the cradle of justice. Now it was akin to boarding an aeroplane. Bag screens, security guards, interrogations. Alan joined the queue, showed his Home Office identity card and was filtered through. At the first trial 13 years before in 1995, he had pushed open the double doors, waved his warrant card at a disinterested member of the court staff and that was that.

Eventually he was through to the main area of the court building. This was far more familiar territory. A cavernous, marbled hallway with statues lining its sides. Courtrooms led off on the right hand side, Courts 7 and 8, Court 19. All playing out their tragedies. Alan thought to himself how often he had been to this building, now it was probably his last time. He knew where he was headed, to the far end, No. 1 Court. The most infamous, but, oddly, one of the smallest courtrooms.

A crowd had already gathered around the heavy wooden benches near to the entrance of the court. A hub-bub of conversation interspersed with laughter. High above them inscribed into the wall unnoticed and embossed in gold-leaf, the statement:

“Defend the children of the poor.

And punish the wrongdoer.”

The irony of this pronouncement always brought a wry smile to Alan’s face. “So long as you have the money,” he thought.

He saw Roger Boydell-Smith standing deep in conversation with one of the detectives of the investigating team. Roger was instantly recognisable, shaven head, tall, easy smile, his charm enhanced by a not forgotten Lancashire burr. Roger broke off his conversation and walked over.

“Morning Al, bit of a circus here today.”

“I hope we’re going to get in. The world and his dog have turned-up.”

“Don’t worry, I’ve been given these by the SIO.”

Roger handed Alan a small piece of paper with his name on it and a short printed authorisation to enter the courtroom.

Alan scanned his eyes over the slip. “Very good of them,” he said, unable to keep the sarcasm out of his voice. “I think Rog, we had better get in while we can, we don’t want to miss this.”

Roger was coming to the end of his service as a detective in the Metropolitan Police Service. A bright, easy going man, Alan had first worked with him when they had both been seconded to the investigation of the murder of Samantha Bisset and her daughter Jazmine. Roger had been appointed as exhibits officer. They had worked together daily for nearly two years on that case and, subsequent to that, had remained friends and taken an interest in the ongoing life of Robert Napper. The man they were here today to see.

They entered the double swing doors, the brass plate gleaming with its bold lettering: “Court 1.” An usher studied their passes and directed them to seats at the rear. Behind the expansive doors the courtroom was surprisingly small but what it lacked in size it more than made up for in atmosphere. In this room the famous and the infamous had been examined and cross-examined, their lives in the balance, from Dr Crippen to Reginald and Ronald Kray. They had risen from the cells below, up the narrow staircase and into the defendant’s box, known as the dock, to plead their cases. Many were to retrace their steps one last time to take their places in the condemned cell.

Roger and Alan each took their seats in the rapidly filling courtroom. Bewigged barristers chatted together on the benches below. The judge’s bench, high at the rear, stood empty. A buzz of excitement was in the air. This was going to be an extraordinary moment. Alan looked across the courtroom; he recognised a few of the faces but most were unknown to him. Thirteen years had passed since the first trial, which had been in the same place and was an affair of much lower profile and of little public interest. Indeed he had been surprised today’s case was listed for No. 1 Court. Probably some last minute shuffling of available venues.

No chat passed between Alan and Roger. The business of the judiciary went on around them, oblivious to their part in the drama. Time ticked on until suddenly the blue of a prison officer’s uniform popped-up into the dock, a hush fell over the courtroom and eyes turned in the officer’s direction. A moment later Alan could see the back of the man he instantly recognised even though the man’s face was turned away from him looking towards the judge’s bench. Wearing an open-neck, checked shirt, his hair was thinning, but still parted schoolboy style. His long neck still carried the scars of childhood acne. His name was Robert Clive Napper.

Moments later an usher intoned, “Silence in court. Stand.” A brief shuffling of papers and backsides off seats, then as demanded … silence. The red-robed judge, Mr Justice Griffith Williams took his place on the high dais and sat down, the rest of those in court followed suit. The prisoner was asked to stand. Alan was now able to get a much clearer view of him as Napper rose to his feet and looked straight ahead at the judge. As the charges were read, Napper looked slowly right and left as if searching for someone in the arena before him. Alan had a clear view of his profile, the slightly protruding teeth over a weak chin and thought how prison life must suit him, he had hardly aged.

The words of the clerk droned on. Alan was having difficulty concentrating, the event was so overwhelming.

“… Murder … Rachel Nickell on …” A clarification was made on the plea. Napper would plead not guilty to murder but guilty to manslaughter by reason of diminished responsibility, then the briefest of pauses.

“And how do you plead?”

A longer pause, then almost inaudibly, in a voice which stumbled slightly over the one word, Napper replied, “Guilty.”

There was no commotion; the court remained quiet.

David Fisher for the defence made a few comments in which he conveyed Napper’s apology to Rachel’s partner, her son Alex, her parents and her close friends for the “dreadful things he did.”

Napper also wanted to apologise to a certain Colin Stagg.

The judge made his comments. Then he ordered that Napper be returned to Broadmoor Special Hospital and informed him there was little prospect of him ever being released.

Then, the fateful words, “Take him down!”

Napper turned 180 degrees to face the steps. His watery blue eyes stared ahead and for a moment focussed on Alan. There was instant recognition as they held each other’s gaze, Napper hesitated momentarily, his pale blue eyes fixed, a slight smile ghosted onto his lips.

Alan mouthed the words, “Hello Rob.”

Urged on by the prison officer, Napper disappeared down the steps.

Chapter 2

The Start

On receiving his instructions to attend at Thamesmead Police Station on the morning of Thursday 4th November 1993, Alan thought little of it. The case he had been working on was drawing to close, a gangland revenge job in south London. The least interesting of all murder investigations, and generally the hardest work when it came to persuading witnesses to come forward. His detective inspector had told him to report to Thamesmead.

“Sounds like a domestic,” he had said, as if intimating this was the bottom of the pile for murder investigation. Alan didn’t mind, anything to get away from the brain-numbing tedium of his current role at Camberwell. He wondered where Thamesmead Police Station was and headed in the general direction of the new high rise estate in south London. Locating it on the map was easier than finding it in reality. Eventually, after driving fruitlessly around the wide, high rise flanked roads in his battered, brown Fiesta, he saw what he was looking for. Set back from the main road, behind a ten foot wire fence, a group of grey prefabs clustered around a blue, MPS notice board. The board, apart from one forlorn leaflet, extolling the virtues of a career in the police, was empty. It was an old building, but not in years. Old police stations, many of which were built around the turn of the nineteenth century of red brick, all to a standard pattern, have a welcoming air, a severe charm seeping from their smog blackened bricks.

Thamesmead Police Station was about as welcoming as a car crash and equally as shocking in its blunt dilapidated façade. No lost property or dog would be readily handed in here. He drove through the open gate which was pinned back with a rusty fire extinguisher and parked his car among several others in the adjoining car park. It was starting to drizzle as he walked across the uneven tarmac. Wearing a threadbare grey suit, the attire worn by most detectives, he nevertheless felt overdressed in the landscape of grime. He entered the unwelcoming public front office. A uniformed officer stood behind the desk, which more resembled a barrier than a place to greet and assist the public. Alan thought fleetingly, “No wonder they call it a ‘jump’.”

He flashed his warrant card and the constable unbolted and lifted the flap pointing vaguely towards the only door. Walking through it and within ten feet, Alan found himself in the incident room where the usual organized chaos was underway. Detective Sergeant Bob Thomas was clearing an area from which he could command the office. Alan introduced himself as Bob tore his eyes from the mounting paperwork.

“Hello. Write your name up on the board will you?”

He pointed to one of three large white boards fixed to the wall, Alan added his name to the seven already appended. Next to Bob his indexers, Enid Lamb, Pam Robinson and Jane Stutchbury beavered away, constructing in-trays for messages, statements and all other forms of paper communication. In the centre of the largest desk was a big steel wheel known as a carousel. The wheel was divided into sections kept apart with headlined index cards. Enid was telling Pam,“I think this should have gone on HOLMES, don’t you?”

HOLMES (Home Office Large Major Enquiry System) was the establishe...