“Are you telling me that you built a time machine... out of a DeLorean?”

Marty McFly, Back to the Future

IN A CITY that is both mar and muntanya (sea and mountain) Barcelona has no shortage of stairs. There is, however, a set that is less well-known. This secret stairway winds itself up from the upper part of the Sarrià neighbourhood, starting at the world-renowned Montserrat school and delivers you into the main square of the village of Vallvidrera. Now, if you were to climb these 477 steps you would surely be tired but happy to enjoy the best views of the city of Barcelona.

Let’s say you devise a strategy to make those 477 steps a little less daunting. Good practice in fields such as learning or athletic training would advocate breaking a big goal down into bite-size chunks. Maybe taking 40 steps at a time then pausing for breath would seem a reasonable approach. So where do those 40 steps take you? A little less than 10% of the way to enjoying those fabulous views (and perhaps a well-deserved refreshment in the town square), right? What if we change the scale? Do you know where 40 steps would take you if we substituted the linear scale for an exponential one? The moon!

We present this vignette as a way of understanding the shift in mindset that is happening today in many areas of society, from technology advance to population increase. Many people believe we are at a tipping point in human history, with an artificial intelligence-driven near-future ready to bring about unprecedented levels of change.

Arriving at the moon is an appropriate image, with ‘moonshot thinking’ being increasingly employed by ambitious, innovative, and disruptive organizations worldwide. First coined by Google X in 2010 (now simply X after the group name change to Alphabet in 2015) moonshot thinking is inspired by the original moon landing in 1969 – an incredibly difficult thing to do, with little actual understanding at the time of setting the goal of how to actually do it. Aiming for the impossible and starting from scratch are therefore two of the defining factors of moonshot thinking. The combination of “a huge problem, a radical solution to that problem, and the breakthrough technology that just might make that solution possible” is, according to X, the essence of a moonshot.

Though pioneered by a business, much of the focus is on grand challenges that face society as a whole. Examples within the X portfolio include Waymo, the self-driving car, and Project Loon, which aims to bring the internet to the most inaccessible parts of the world via hot-air balloons. Projects ‘graduate’ when they are mature enough to be developed within another part of the business, including Google Brain, which is driving development in artificial intelligence.

| Aiming for the impossible and starting from scratch are therefore two of the defining factors of moonshot thinking. |

The change in thinking where failure is celebrated (even encouraged) and short-term value is eschewed in favour of the deep learning that drives long-term leaps needs a supportive environment, of course. It also needs people who have a deep passion for what they are doing on a day-to-day basis. Will we be able to create a critical mass of these passionate, supportive environments to truly realize a shift to exponential progress?

Tim Urban covers many of the key points related to the changes likely to be driven by artificial intelligence on his popular Wait But Why blog. He presents an accessible and amusing overview of AI, introducing concepts such as the Law of Accelerating Returns developed by the futurist Ray Kurzweil. In a nutshell, the next 30 years will return a far greater level of progress than the previous 30 years, and so on. As an example, Kurzweil suggests that the progress of the entire 20th century would have been achieved in just 20 years at the rate of advancement experienced in the year 2000.

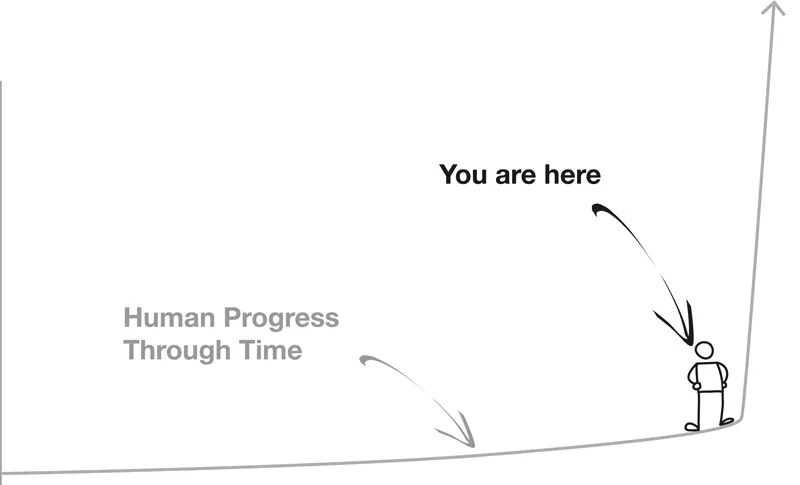

Figure 1.1. Human progress through time, adapted from The AI Revolution: The Road to Superintelligence by Tim Urban

Why is it so difficult to fully absorb the difference between linear and exponential progress? After all, the concept of exponential growth as related to the internet age has been gaining momentum for several years – ex-Google CEO Eric Schmidt said in 2010 that “we create as much data in two years as we did from the dawn of civilization up to 2003”, yet it remains a difficult concept to grasp. More recent commentary, such as ‘what happens in an internet minute’, often takes on the numbers-heavy tone of world economics that results in most of us simply glazing over.

Getting to the moon through 40 exponential steps may allow a greater impact of the scale of change to hit home. A possible explanation for the general difficulty may be appreciated in the figure below, which helped frame Urban’s analysis. Simply put, we can’t see into the future. And the near future, according to Urban and many other AI commentators, is likely to yield significant advance due to the current status of computing power. Today, a $1,000 machine has around the equivalent processing power of a mouse (around 1/1000 of a human brain), yet continuing this trajectory using Moore’s Law and other accepted historical trends will yield the equivalent of human intelligence by 2025 – with the sum of all human brains on Earth to follow soon after.

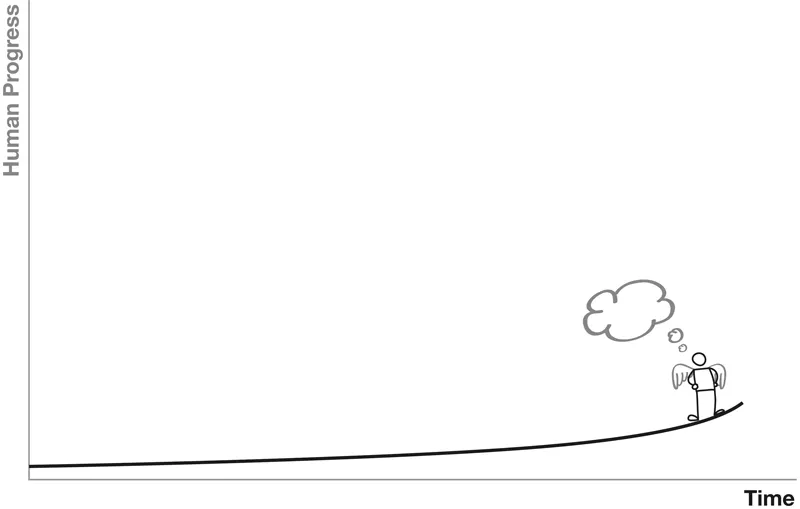

Figure 1.2. Human progress to the present day, adapted from The AI Revolution: The Road to Superintelligence by Tim Urban

| We wanted flying cars, instead we got 140 characters. |

Not everyone agrees that this line is about to dramatically kick-up. When we arrived at 21 October 2015, the date at which Marty McFly was shown to arrive in Back to the Future Part II, there was a societal shrug of the shoulders and a palpable sense of disappointment.

On more careful reflection, 21 October 2015 did indeed have an abundance of innovation and progress in comparison to 1989, when the sequel was originally released. Many of the future ideas, including virtual-reality movies, roll-up TV screens, and drones do exist in some form today, while the really big ideas, such as flying cars, may not be as far off as we think, given the rapid development of drone technology and the start of services such as drone-powered flying taxis in Dubai. In general, it’s hard to be too critical when we consider that the World Wide Web only came into existence the same year the film was released, with the first web browser not coming until the following year.

Nevertheless, dissenting, disappointed, and underwhelmed voices exist. PayPal co-founder Peter Thiel wrote in 2010 that the technology industry had let people down, saying that “we wanted flying cars, instead we got 140 characters” (in a clear reference to Twitter).

Taking a more optimistic stance in his role as guest editor in the November 2016 issue of Wired magazine, Barack Obama said that now is the best time to be alive. The core message of Obama’s editorial is people coming together to achieve big things. In spite of the undoubted progress that underpins his principal statement, he notes with optimism the great challenges that lie ahead, including climate change, economic inequality, cyber-security, terrorism, and cancer. The final months of his administration in Autumn 2016 also included the formation of a taskforce to tackle a Cancer Moonshot.

Part of the inherent logic in Obama’s statement is that any present date is the best time to be alive, precisely because of the progress we make as a human race. So tomorrow, next week, and next year should be viewed as the best times to be alive respectively. Apart from being a boon to mindfulness advocates worldwide, the predictions of our move to more exponential progress should see the relatively near future as providing ever greater appeal, provided we adopt the right mindset to deal with massive change; change, of course, not being the most palatable concept for most of us.

Healthier than ever before, and happier?

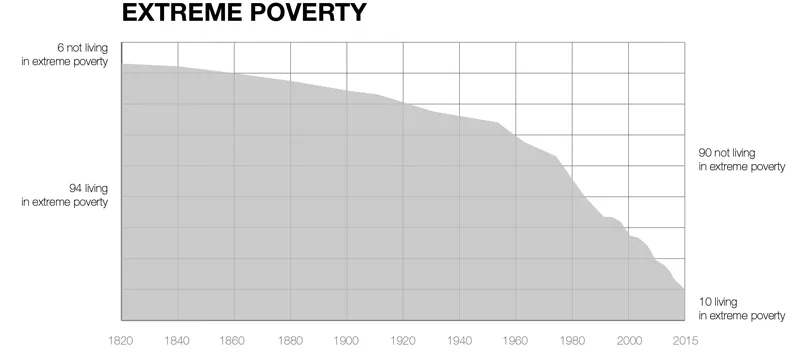

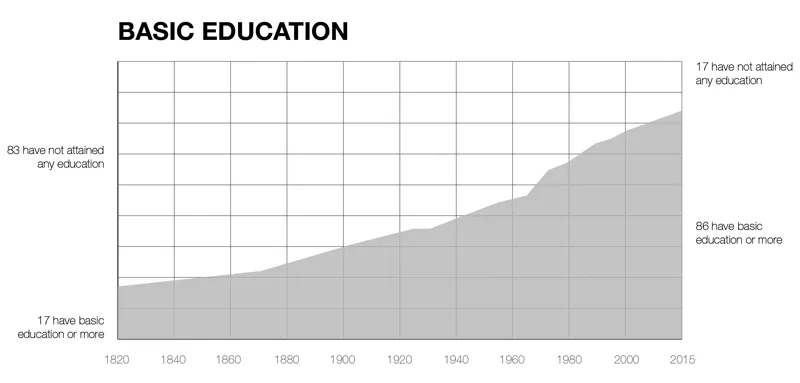

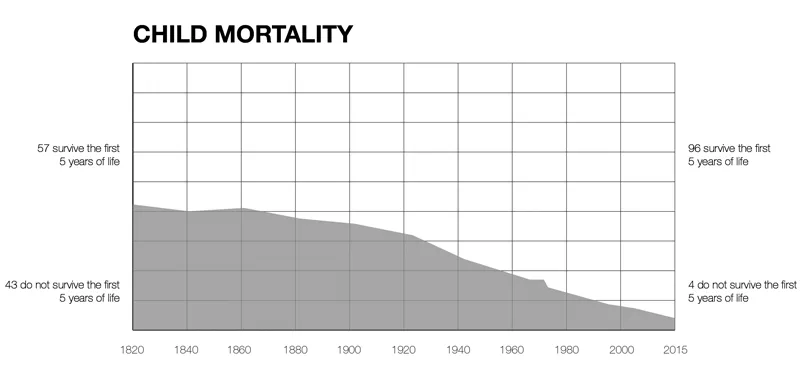

There is no doubt we are progressing as a human race. Even for the most fervent sceptic of the modern world, all the data points to now being the best time to be alive. Though some argue that we are not moving fast enough, many of the major global development goals, with the exception of income inequality, are going in the right direction. Extreme poverty is decreasing around the world, average life expectancy will soon hit 90 years in certain developed countries, and people including Bill Gates – given the significant strides made by the Gates Foundation – hail the achievement of major milestones such as the virtual eradication of polio.

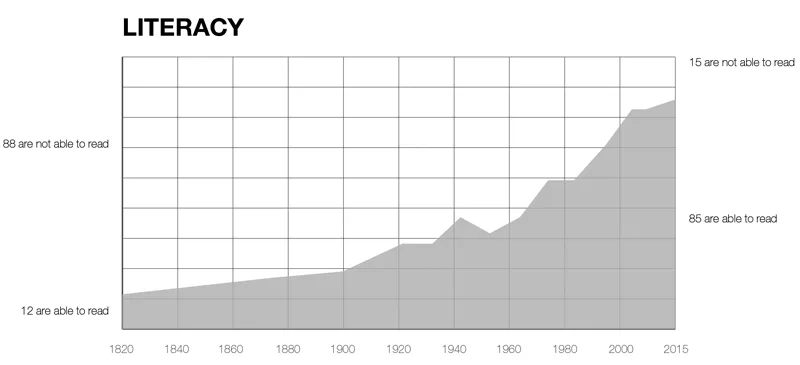

Figure 1.3. The world as 100 people in poverty, education and literacy the past 200 years, adapted from Our World in Data by Max Roser (ourworldindata.org)

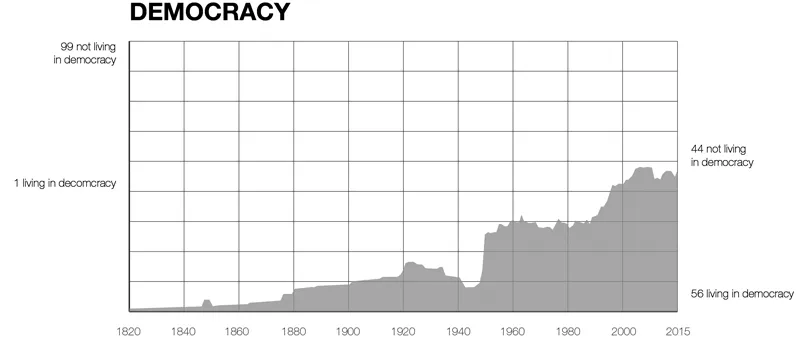

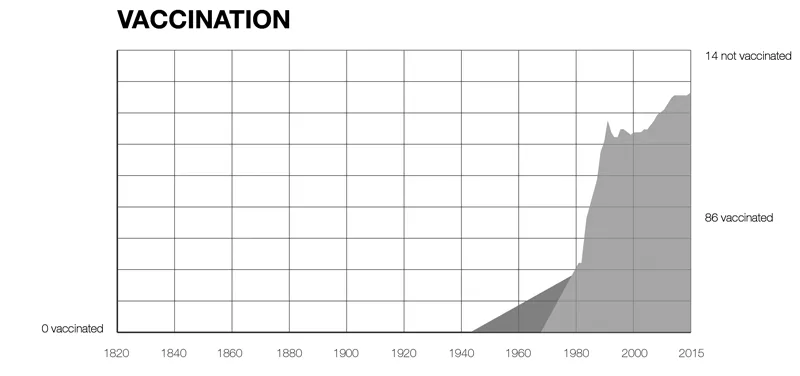

Figure 1.4. The world as 100 people in democracy, vaccination and child mortality the past 200 years, adapted from Our World in Data by Max Roser (ourworldindata.org)

So levels of health, wellbeing and prosperity are unmatched in human history. Yet are we really happier than ever before? The first World Happiness Report by the United Nations was released in 2012. Since then the UN believes there to be increasing evidence of happiness being considered the proper measure of social progress and the goal of public policy – something we look closer at in chapter four. Norway tops the happiness rankings in the latest report, while also experiencing a significant drop in oil prices. Note is made that the country “chooses to produce its oil slowly, and invests the proceeds for the future rather than spending them in ...