![]()

| ONE THE PHOENICIAN

HOMELAND: HISTORY AND

ARCHAEOLOGY |

The Phoenicians are a clever branch of the human race and exceptional in regard to the obligations of war and peace, and they made Phoenicia famous. They devised the alphabet, literary pursuits, and other arts too; they figured out how to win access to the sea by ship, how to conduct battle with a navy, and how to rule over other peoples; and they developed the power of sovereignty and the art of battle.

So wrote the Roman author Pomponius Mela in his De situ orbis (Description of the World) in the first century CE.1 He, like many others in the ancient world, admired the Phoenicians for their contributions to human civilization. In this chapter, we will consider the history of Phoenicia by placing it in the context of the Ancient Near East and introduce the major events, themes and topics of both the Phoenician homeland and the broader Mediterranean. Our focus will be on the period from 1200 BCE to the end of the Persian period (332 BCE) – the scholarly consensus regards these centuries as the time when the Phoenicians were most visible on the international stage, although we will briefly venture into the Hellenistic and Roman periods as well. We will also address the material culture (mostly pottery, burials and building remains), either to derive missing information or to test the evidence drawn from written sources. We will focus mostly on homeland Phoenicia, understanding that Phoenician colonizers in the Mediterranean, once having established their bases, would develop and sustain their new artistic and cultural traditions with only a tangential nod to the heritage of the Phoenician homeland.

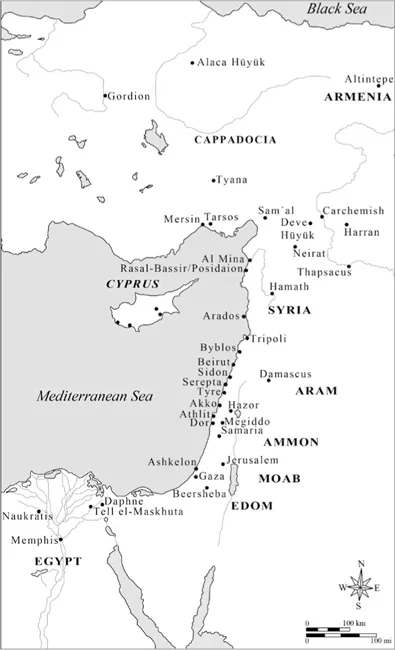

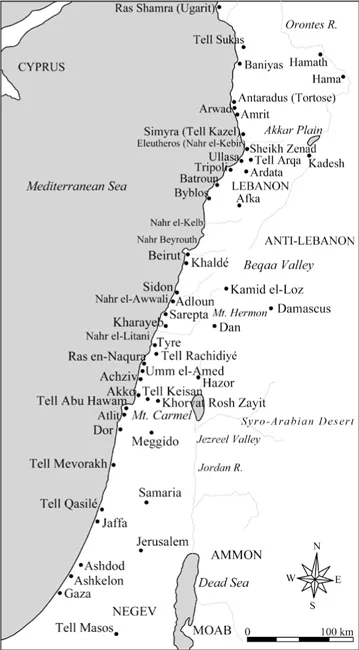

Phoenicia and neighbouring territories.

Geography and climate of Phoenicia

Geography was crucial in the social, cultural and political life of Phoenicia, at least in the minds of the classical authors who envisioned and defined it. Although Graeco-Roman writers thought of Phoenicia as a land between the Gulf of Alexandretta (İskenderun, on the coast of modern Turkey) to the Gulf of Suez, in reality the Phoenician homeland occupied a relatively narrow strip of land (10 kilometres at its widest) stretching from southern Syria to northern Palestine between the Lebanon Mountains and the Mediterranean Sea. That land was further naturally divided by rivers and mountains, including the Anti-Lebanon Mountains, which run parallel to the Lebanon Mountains and which served as a natural border between Phoenicia and Syria. Protected from the east by the mountain range, the people inhabiting Phoenicia had an easier and more secure environment in which to set up and develop a system of urban settlements. The coastal location afforded additional opportunities for seafaring as the two largest polities, at least initially, Arwad and Tyre, were island city-states, providing an easy way to sail westward. Opportunities for agriculture were provided by the Beqaa Valley, rising about 1 kilometre above sea level and located 30 kilometres to the east of Beirut between the Lebanon and Anti-Lebanon mountain ranges.2 Two rivers flowing through the valley, the Orontes and the Litani, kept it well irrigated for growing crops.

The climate of Phoenicia was more or less comparable to that of modern Lebanon, as palaeoenvironmental evidence based on the study of tree rings has suggested.3 In essence, it was a Mediterranean climate with subtropical characteristics. In winter, storms from the Mediterranean moved eastward, bringing with them abundant precipitation (750–1,000 mm) and mild temperatures (around the low 10s Celsius), but summertime was usually hot and arid, with temperatures reaching the low 30s Celsius.4 Temperatures and precipitation would vary depending on the location, higher altitudes receiving more rain (and snow in wintertime). Such a climate afforded the growth of many kinds of trees, including cedar. A valuable resource for shipbuilding and construction in ancient and medieval times, cedar is the symbol of Lebanon and is even prominently featured on its currency.

Phoenicia’s earliest periods

The territory of what we consider Phoenicia was continuously occupied from the dawn of humanity. The earliest artefacts, sharpened splinters of flint dating to around 700,000 years ago, were discovered in Borj Qinnarit, near Sidon, and traces of human occupation in Lebanon have been discovered at dozens of Stone Age sites.5 Josette Elayi points out that the three main habitat types from that period are caves, rock shelters and open-air settlements.6 We have little concrete information about those earliest societies, but we can surmise that they were primarily hunter-gatherers. However, things started to change in the Chalcolithic period (also referred to as the Copper Age, c. 4500–3500 BCE). This period is best illustrated by the findings at Byblos, Sidon-Dakerman (near Sidon), Khalde II and Minet ed-Dalieh, on the Lebanese coast, and the inland sites of Mengez and Kfar Gerra.7 From 1924 to 1975, Maurice Dunand, a French archaeologist, carried out thorough excavations at Byblos, the longest continuously occupied site in Lebanon. Our knowledge of the entire chronology of human occupation of the Lebanese coast is based primarily on his work there. Among the features of Byblos and other Chalcolithic sites is the emerging use of jar burials (besides plain and cave burials) accompanied by a great variety of burial goods. Another prominent feature of the Chalcolithic era is the organization of dwellings into private houses, silos and paved roads. Private houses were primarily single-room stone-walled constructions reaching a size of 6 × 9 metres and evolving either into circular or square dwellings by the end of the Chalcolithic period.8

Based on the close proximity of dwellings to burial sites, archaeologists conclude that the Chalcolithic societies in Lebanon were mostly sedentary, with no clear social hierarchy, as burial goods comprise symbols of power (weapons) as well as everyday goods.9 Burial goods are indispensable for archaeologists, since valuable conclusions can be derived from even the most pedestrian objects. For Chalcolithic Phoenicia, these bone artefacts, pottery, ornaments and metal objects provide clues about human occupations, which included herding, agriculture, fishing, hunting and crafts. The grave goods also reveal that Chalcolithic pottery was rather plain and made without the use of a potter’s wheel, suggesting that the pots were produced for everyday use in the shortest time possible. A gradual move away from bones to metals is characteristic of all Chalcolithic societies, and the burial goods in Phoenicia illustrate this process by the use of copper arrowheads for weapons and silver ornaments. Overall, the Chalcolithic period was a transitional time between the Neolithic period and the Bronze Age, and it introduced several technological developments that paved the way for societal progress in later eras.

Phoenicia in the Early Bronze Age

The Early Bronze Age (c. 3500–2000 BCE) is largely a mystery for the study of Phoenicia. There are 140 known sites that have not yet been excavated, and those that have been excavated have not yet been fully described.10 The sites of Byblos and Sidon-Dakerman are again the ones that have provided most information. Jar burials are again attested, but there appear to be emerging signs of social stratification, as some burial goods include gold and silver jewellery whereas others have much more modest goods.11 The earliest pottery from the period is still shaped by hands, but in Byblos we now encounter decorated jars and red and reddish-brown slip (a mixture of water, clay and a pigment used for decorating pottery). Stamp seals, used for marking the ownership of objects, appear on handles and shoulders of some burial jars.12 Tools are mostly made of flint, although the use of copper and silver is present as well.

From an architectural point of view, residential dwellings mostly comprised several rooms, and the buildings themselves, constructed using either limestone or mud-brick, were arranged along narrow streets.13 Burials shifted towards rock-cut tombs at a distance from the settlements. Such tombs were multi-use, possibly belonging to a single family or dynasty. With time, significant strides were made in pottery production in the Early Bronze Age, evidenced by the introduction of the potter’s wheel and a proper kiln. These innovations in turn initiated the process of the standardization of pottery types throughout the entire region.14 Hunting became less important because of the density of populated areas, and fishing and herding replaced it to become the major sources of food.

Egypt becomes a major player in Lebanon in the Early Bronze Age. Byblos was the main recipient of Egyptian interest from at least the beginning of the third millennium BCE, although Tyre and Sidon participated in trade with Egypt as well. The main attraction for Egypt was timber in the hinterland regions of Byblos along with resin used in mummification, although agricultural products such as wine and olive oil were also valuable imports.15 It was not a one-way movement of goods, however, as the presence of imported materials in Byblos such as metals and obsidian hints at the wide-ranging commercial network in which the city was involved.

The end of the Early Bronze Age shows indications of instability in Byblos, and archaeological excavations reveal signs of a major calamity towards the end of the third millennium BCE (Egyptian stone vases, gifts from pharaohs to the royalty of Byblos, covered by a thick layer of ash).16 Historians have traditionally explained that this instability was caused by raids by the Amorites, semi-nomadic tribes of Syrian origin. However, recent studies reject this proposition, since the destruction in Byblos is not present at other sites. Among the recent proposed explanations is a combination of climatic changes and intraregional competition for dwindling natural resources.17 The tumult at Byblos did not result in its demise, however, as the city restructured and continued to exist and prosper.

Middle Bronze Age (2000–1550 BCE)

Many of the changes that started in the Early Bronze Age continued in the Middle Bronze Age. This was a generally peaceful time that witnessed developments in technology and trade among many Phoenician sites, such as Arqa, Byblos and Sidon.18 Byblos recovered from the destruction of the previous period and renewed its ties with Egypt, which were broken for a short time in the First Intermediate Period (c. 2150–2030 BCE).19 The rise in population, observable even in the Early Bronze Age, intensified, leading to the emergence of new urban centres near sources of water, especially in the Akkar Plain and the Beqaa Valley. In an atmosphere of competition for natural resources, emerging mini-states controlled smaller settlements, the latter contributing agricultural products in exchange for protection from the former. The coastal sites, usually located near natural bays for the ease of anchoring ships, were situated 15–20 kilometres from each other, which most likely indicated the scope of their influence.

Much attention in this period was paid to fortifications, and the ramparts at Byblos, Kamid el-Loz, Arqa and Beirut hint at both the existing threats and the means of construction. Domestic architecture, characterized by comparatively sizeable houses with in-house ovens and basalt grinders, suggests a new level of prosperity. Religious architecture has been discovered mostly in Byblos, which boasts the largest number of Middle Bronze Age temples in Lebanon. The most famous of these is the Temple of the Obelisks, a well-preserved sanctuary built on a podium and surrounded by a courtyard. The obelisks are the central feature of the temple, and one of them bears a hieroglyphic inscription mentioning the Egyptian god Herishef-Rê, possibly the god to whom the sanctuary was dedicated. Burial customs evolved in the Middle Bronze Age, leading to the introduction of four new burial types: the shaft tomb, the pit burial, the cist burial and the built tomb.20 Whereas adults were usually buried in these, infants and children were typically interred in storage jars, their remains within arranged in the foetal position. That and the fact that many burial goods included everyday pottery may suggest that the Middle Bronze Age saw the development of nascent beliefs in an afterlife.21 Sometimes burial sites were reused, although jar burials were usually one-use vessels. Food offerings often accompanied burials, and they included both meat (mutton, goat, beef, pork) and bread and beer, as was the case in Byblos. Conceivably, burials were followed by funerary banquets, as burial locations in Sidon are accompanied by the remains of ovens.22 It is not clear, though, whether the banquet was a feature among all Phoenician cities.

Pottery became diversified in the Middle Bronze Age, and decorative embellishments continued from the previous era. Pottery came in handy for...