![]()

PLAYSCRIPT

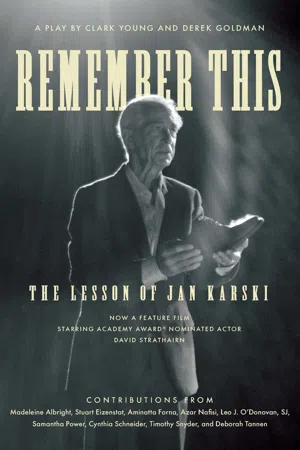

REMEMBER THIS

THE LESSON OF JAN KARSKI

Featuring David Strathairn

By Clark Young and Derek Goldman

Directed by Derek Goldman

Produced by The Laboratory for

Global Performance and Politics

Adapted into the film Remember This

Directed by Jeff Hutchens and Derek Goldman

Produced by Eva Anisko

A space with a desk and two chairs.

A man addresses the audience.

MAN

We see what goes on in the world, don’t we?

Our world is in peril. Every day, it becomes more and more fractured, toxic, out of our control. We are being torn apart by immense gulfs of selfishness, distrust, fear, greed, indifference, denial.

Millions are being displaced, impoverished, denied justice simply because of who they are, beaten, murdered, silenced, forgotten.

We see this, don’t we? How can we not see this?

So what can we do? What can you do? What can I do?

What can we do that we are not already doing?

Do we have a duty, a responsibility, as individuals . . . to do something, anything?

And how do we know what to do? How do we know what we are capable of?

It’s not easy—knowing.

Human beings have infinite capacity to ignore things that are not convenient.

Human beings have infinite capacity to ignore things

that are not convenient.

A clip plays from Claude Lanzmann’s documentary Shoah.

In the clip, after a silence, Jan Karski tries to speak and breaks down:

“Now . . . now I go back . . .

Thirty-five years.

No . . . I don’t go back.

As a matter of . . .

Alright.

I come back.”

Jan Karski leaves the frame. The clip ends.

“No . . . I don’t go back.”

MAN begins to get dressed.

Jan Karski.

Born Jan Kozielewski, 1914.

Messenger of the Polish People to Their Government-in-Exile.

Messenger of the Jewish People to the World.

The Man Who Told of the Annihilation of the Jewish People While

There Was Still Time to Stop It.

A Hero of the Polish People.

Professor. Georgetown University, 1952 to 1992.

MAN becomes Jan Karski.

And always immaculately dressed.

And always immaculately dressed.

Now I go back . . .

In my classes on government and politics I tell my students . . .

He steps forward, as if addressing a classroom of students.

Governments have no souls. They have only their interests in mind.

What is your duty as an individual?

Individuals have souls.

The common humanity of people, not the power of governments, is the only real protector of human rights.

So I ask you: What is your duty as an individual? Every generation takes up a new revolution.

Szmul Zygielbojm. Remember his name. This man loved his people more than he loved himself. Zygielbojm shows us this total helplessness, the indifference of the world.

What we are witnessing now is very discouraging. Every generation brings destruction, partition, violence, and yet there is this desire to preserve language, identity, culture.

As a boy in Poland, we had to learn many languages because we never knew who would take us over!

///

For thirty-five years . . . I have never mentioned, even to my students, that I took part in the war.

I wanted to forget that degradation, that humiliation, that dirt.

I was forgotten, and I wanted to be forgotten.

One day, in 1978, I am discovered.

He knocks on the desk.

A man knocks on my door. A filmmaker.

His name is Claude Lanzmann. He is very full of himself . . . he likes to brag . . .

(as Lanzmann)

“I am making a film. It will be the greatest film ever made about the tragedy of the Jews. It will be called Shoah, and it will be as long as it needs to be to tell what needs to be told. Professor Karski, you will be in this film. There will be no actors. No Hollywood nincompoops. Only perpetrators, victims, witnesses. You are in the third group. I will have an interview with you.”

(to Lanzmann)

“You will not have an interview with me. I’m out of it.”

I remember, he is a bit of an authoritarian, he is very pushy . . .

(as Lanzmann)

“Professor Karski, look at the mirror. You are an old man . . . You are going to die soon. You have an historical responsibility. It is your duty to speak.”

He convinces me.

I made a fool of myself . . . I broke down a few times. It was the first time I was involved again in that experience.

My wife, Pola, she can’t stand it. We never discuss the war.

(as Pola)

“Jan, you torture yourself. You have done your job. It does you no good.”

She leaves the house, walks for four hours. She’s a dancer; she never stays still.

Lanzmann asks me questions . . .

(as Lanzmann)

“Do you think you succeeded in your report to the world?

Do you think you succeeded in conveying the magnitude?

Professor Karski, you are a unique witness. You are a hero . . . ”

(to Lanzmann)

“No, no . . . I am an insignificant, little man. Hero? No!”

People in Poland were not happy I participated in that film. They say it does not reflect kindly on my country . . .

I am an insignificant, little man. Hero? No!

///

I was born in Łódź. At that time, one of the most multicultural cities in all of Europe, where, whether you are happy or unhappy, you always hear bells.

I remember, my grandmother gives me a bicycle.

(as Grandmother)

“Jasiu,” she says. “Take this. See the Polish countryside, as it is now.”

I ride east to west. Everywhere I go . . .

(as Poles Passing By)

“Witam! Witam, Jasiu.” “Dzień Dobry!” “Powodzenia!” Good luck.

By American standards, we are rather poor. My father, Stefan Kozielewski, has a small factory producing saddles, women’s bags, leather goods . . . I barely remember him; he dies when I am very young.

My mother, Walentyna Kozielewska, wants me to be a diplomat, an ambassador of Poland. I work hard. I listen. Everyone says I have an excellent memory . . . I am a good boy.

My mother is very, very Catholic . . . devotion, respect for others. She is making us in her image . . .

I remember, she tells me that when they took me to be baptized . . . my father, my godfather, my priest—all of them were drunk. She is disgusted, but this is Poland. In America, people drink to be in a better mood. In Poland, we drink to get drunk.

Now, I think every conversation would be better with a Manhattan.

///

In our apartment house, I remember, in the yard, some boys, children—whom my mother calls “bad boys.” They would sneak and over the roof they would throw dead rats.

(as Mother)

“Bad boys. Bad Catholic boys teasing the Jews. Throwing dead rats at the Jews. Jasiu, keep watch, like a good Catholic boy. Go to the sukkah, where the Jews pray, and watch.

“Go to the sukkah, where the Jews pray, and watch.”

If someone comes, simply call, ‘Mamo, mamo.’ I will take care of them.”

And I watch.

///

My best friends at school are Jewish.

They help me in science. I help them in Polish literature, history.

Izio Fuchs, extremely religious. Everybody calls him a Jewish prophet. He starts every sentence, “I say.”

Another one, Lejba Ejbuszyc. Abject poverty, a fighter. Full of resentment, hatred. He must have been badly treated.

Izio tells us . . .

(as Izio)

“I say . . . we have to be friendly to Lejba because if he doesn’t find friends with us, where will he find friends?”

Izio’s younger brother, Salus. Everybody likes Salus, but I like him most of all. He wants to be a pianist. But I can never get him to play the piano for me.

I don’t know what happens to them.

My mother always says . . .

(as Mother)

“Jasiu. Climb the ladder. Nothing will stand in your way. Go. Go.”

I leave Łódź for University to study law and diplomacy.

///

After graduation, I am invited to attend a youth rally . . . in Germany.

The enormous roar of a crowd.

Thousands of faces, all somehow the same. Tremendous hullabaloo. Tremendous hall, like a concert, a circus. Darkness, shock. Nothing is happening. Then the sun descends on one point alone. A man, medals on his chest, light glowing around him . . .

That is Hermann Goering.

(as Goering)

“You have to take responsibility for the human race! Because you belong to the superior race! We are destined to govern, to bring order to the world, to create a lasting peace! And only the honest, decent youth of Germany can make such peace. Seig Heil! Seig Heil! Seig Heil!”

The sound of the crowd echoes and dissolves.

What is happening? That was Goering.

It’s enough to make someone dizzy, the noise, the lighting. But . . . I think . . . maybe they are superior—to govern the whole world is a pretty overwhelming proposition, yet it sounds like fun to them. Why couldn’t I be born German, I wonder, so I could be superior too?

To me, at this moment, they represent Western civilization.

///

Why couldn’t I be born German, I wonder, so I could be superior, too?

I go to Geneva to learn French, then London, to learn English, which is very, very difficult. I work a low-level job in the Polish embassy . . . but I feel . . . I have a longing for home.

Polish folk music plays.

One evening, I go to the theater. An evening of Polish folk dance.

Alone on stage, dancing, barefoot, a girl, a Polish girl of outstanding beauty . . .

Her name is Pola. A Polish girl named Pola. Pola Nirenska.

A girl in exile here, far from home . . . what story is she telling with such urgency, such freedom? I have never experienced this form of express...