- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About this book

Running your own practice can bring immense job satisfaction, but it is not without its risks. Do you have all the information at hand to set up confidently on your own? Comprehensive, accessible and easy to use, Starting a Practice helps architects navigate the pitfalls associated with establishing a successful business. This fully updated 3rd edition is mapped to the RIBA Plan of Work 2020 and approaches starting a business as if it were a design project, complete with briefing, sketching layouts and delivery. It features new material on professionalism and ethics, sustainable development and achieving a net-zero carbon emission built environment. Invaluable for Part 3 students, early practitioners and those considering setting up from scratch or wanting to consolidate an existing business, Starting a Practice gives architects the tools they need to thrive when setting out alone. Features essential guidance on:

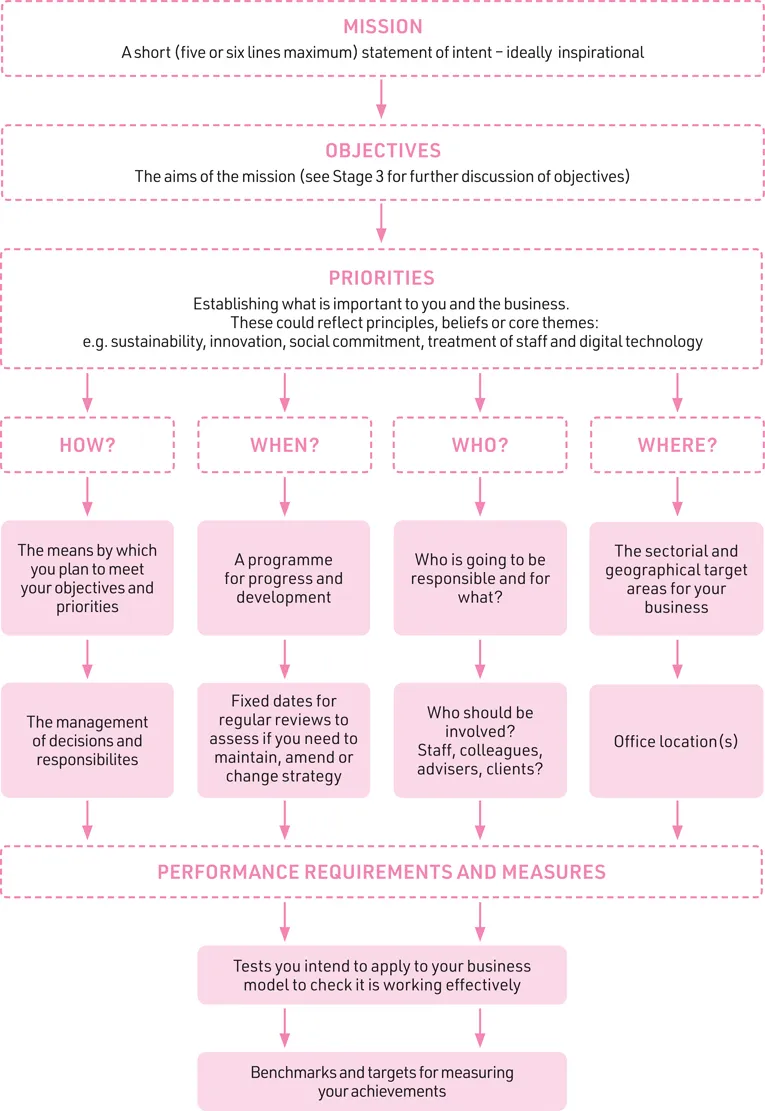

- Preparing a business plan

- Choosing the right company structure

- Setting aspirations

- Monitoring finances

- Getting noticed

- Securing work

- Retaining and developing staff

- Planning for disaster.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

STAGE 1:

Preparation and Brief

An essential section on getting the basics right before setting up your business – by assembling a written brief and investing in as much preparation as possible.

SETTING OUTCOMES AND ASPIRATIONS

- At any one time governments are working on a number of long-term policy objectives that may turn into regulation or develop delivery mechanisms that affect you (for better or worse) in the future. These objectives, which may have been described in a Green Paper or consulted on more generally, might include the need to increase house building, deliver energy improvements, better protect the environment or achieve greater equality and diversity in the workplace. If your aspirations are to be meaningful, they should match or exceed such policy goals.

- Many organisations; charities, think tanks and pressure groups, from the UN down, have already developed and tested detailed proposals for how the world and society might be improved or sustained. You might be better off working and making common cause with one or more of these than developing your own individualised set of outcomes and aspirations. This will give you a ready-made community to engage with, and far greater recognition and understanding of what you aim to achieve.

- Organisations you might already belong to, for example the RIBA, may provide advanced notice of programmes for delivering change. In the RIBA’s case its future proposals for CPD requirements are set out in its August 2020 document ‘The Way Ahead’1, and carbon and other output targets and performance milestones in its 2030 Climate Challenge2.

- Systems may already be in place for delivering and validating some long-term goals, for example the Passivhaus method for achieving comfortable low-energy buildings, or building information modelling (BIM) protocols for digital design and management processes. These might require training and accreditation or require you to work in prescribed ways, but could give you a genuine business advantage. Ideally decisions should be made early on as to whether they will be incorporated into your design brief.

KNOWLEDGE AND SKILLS

GLOBAL CHALLENGES

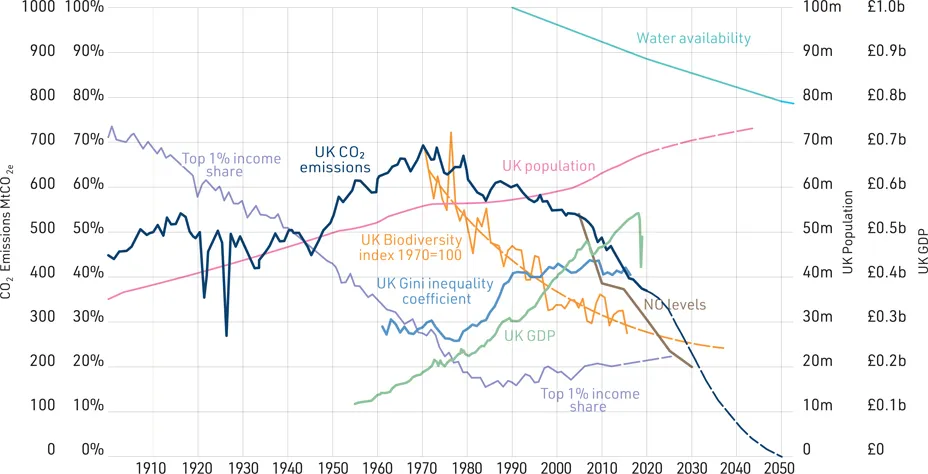

- Climate change and the national commitments made under the 2016 Paris Agreement to restrict global heating to 1.5°C (and certainly 2°C) above pre-industrial temperatures. This has resulted in many countries, including the UK, instigating legal requirements for a net-zero carbon economy by 2050. This will probably require a net carbon positive built environment by that date to offset requirements for fossil fuels in other sectors.Changes in the climate will bring numerous other challenges beyond higher temperatures; including increased drought and flooding, wildfires, insect infestations and changes in prevalent diseases. The need to reduce carbon outputs will require the use of alternative and clean energy sources (and much-reduced use of energy), increased use of natural means for lighting and ventilation; and the need to ensure comfort and wellbeing without recourse to energy intensive systems.

- Land use. How land is prioritised and used will become an even more fraught issue as greater precedence may need to be given to the natural environment in general, trees and forestry as carbon sinks and the growth of energy-yielding crops, while travel distances will need to be reduced and access to infrastructure improved.

- Biodiversity and species loss. This is often described as the most serious of the challenges that the globe (and with it humanity) faces, with the implications yet unknown.

- Water. The availability of clean water is already under strain, and increasing controls over its use and extraction are likely to be introduced.

- Pollution. Air and water quality are already poor across the world, and the measures that will need to be introduced will have a direct impact on the built environment.

- Resource limitations. Certain materials will be in increasingly short supply or the costs, either in cash or carbon, of their extraction or production will become too great to justify their use, except in special circumstances.

- Population. Demographic changes as the world population approaches 11 million by the end of the century from its current 7.8 million3 will mean that some areas get older and less populated while others become younger and far more densely inhabited. Both of these trajectories will present serious issues to future generations.

- Inequality. Inequality in all its forms (wealth, health, education, life expectancy, employment, housing conditions, access to justice, etc.) has been increasing worldwide for many decades, with the ramifications being particularly exposed by the Covid-19 pandemic of 2020. Any remedies for this will be necessarily far-reaching, but the results of inaction may be even more serious.

- Automation. This has been changing the world of work for centuries but it has only recently begun to threaten the livelihoods of professionals, with the advent of systems that can potentially carry out aspects of building professionals’ workloads more accurately, diligently and at less cost than humans. This may mean an increased focus on those skills that are less replaceable – at least in the short term. The same applies to outsourcing.

- Changes in living, working and leisure practices. As seen occurring extremely rapidly during the 2020 pandemic, these trends may continue to develop, leading to new uses for buildings, towns and cities – all requiring design input and expertise.

BUDGET

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Image Credits

- Preface

- About the author

- Contents

- 0 Strategic Definition

- 1 Preparation and Brief

- 2 The Outline Business Case

- 3 The Business Plan

- 4 Business Design - Structure

- 5 Starting up - Setting Out Your Stall

- 6 Keeping Going

- 7 Evaluation and Looking Ahead

- Conclusion

- Bibliography and websites