![]()

1

’Neath Shandon Steeple

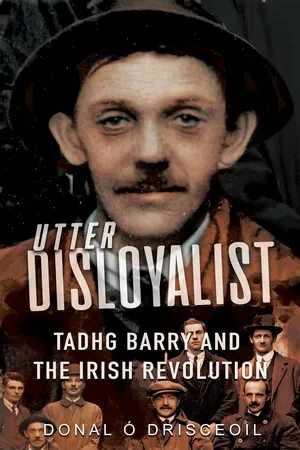

Timothy (Tadhg) Barry was born on 25 February 1880 and grew up on Blarney Street, on the Northside of Cork’s River Lee, in the shadow of Shandon’s famous steeple of the church of St Anne. Cork’s longest thoroughfare, with almost 400 houses and eighteen adjacent lanes, Blarney Street was a thriving, bustling neighbourhood – described by Barry, with typical literary flourish, as a ‘crowded purlieu’– that would become a stronghold of militant Republicanism in the second decade of the twentieth century. The vast majority of the Barrys’ neighbours were Catholic and working class or lower middle class. They were vintners and shopkeepers, cattle dealers and pig buyers, factory workers and dock labourers, blacksmiths and farriers, seamstresses, dressmakers, upholsterers and domestic servants, masons and railway workers, shop assistants and bar workers, barbers, porters, watchmen, weighmasters, shoemakers, coopers, shirtmakers, dairymaids, together with a smattering of clerks, insurance agents and teachers.

Timothy Joseph, as he was christened – he began using the Irish version of his forename, Tadhg, in 1906 – was the fourth child of Margaret (née Murphy) and Daniel Barry. Of his three older siblings, only one, Mary Kate, two years his senior, survived into adulthood, while at least three of his younger brothers and sisters also died as young children, highlighting the precariousness of life prior to the wide availability of vaccines and the discovery of antibiotics and other life-saving medicines. His eldest brother James died aged five from scarlet fever in December 1880, when Tadhg was ten months old, followed two years later by his sister Elizabeth, also aged five, who died from diphtheria. Daniel (b. 1881) survived, later emigrating to South Africa, but the next-born, Margaret, died at three months due to hydrocephalus, or ‘water on the brain’. The twins, Patrick (Paddy) and George, were born in 1885, but the latter only lived until May 1887, when he died from complications arising from a stomach infection. Paddy survived into adulthood but suffered with poor health throughout his life.

Faith, fatherland and socialism

Tadhg’s father, Daniel senior, was a cooper, a strong tra- ditional trade in that area of Cork linked to its long- established butter, provisioning, brewing and distilling industries. As with most of his generation in that era, he supported the constitutional-nationalist movement’s campaign for Home Rule; he was well known and well liked in his neighbourhood and was a Home Rule-party activist; he was a member of the Cork committee formed in December 1890 to support the William O’Brien and John Dillon-led anti-Parnellite faction in the Parnell split. His son later worked for O’Brien’s Cork Free Press and was elected a Poor Law Guardian (PLG) under an O’Brienite banner in 1911. Tadhg Barry eschewed the traditional route of eldest (surviving) sons of tradesmen by not following in his father’s coopering footsteps. Later in life, as a trade unionist, he railed against the closed-craft system that operated in many of the trades – an antiquated arrangement that privileged some on hereditary lines. ‘A boy’, he wrote in 1918, ‘no matter what his father might be – [should] be entitled, by acquisition of technical knowledge, to perfect himself in the handicraft that gives best promise to his talents.’ Barry’s talents lay mainly in journalism and organising, and he later excelled at both, as we shall see.

He was educated in the National school on Blarney Street and then at the North Monastery Christian Brothers secondary school, a fifteen-minute walk from his home. The ‘North Mon’, or simply ‘the Mon’, counts among its alumni the later Republican lord mayors of Cork Tomás MacCurtain and Terence MacSwiney, Cork IRA leader Seán O’Hegarty and his brother, the Sinn Féin intellectual and propagandist P.S. O’Hegarty. The latter claimed that his generation of activists ‘owed their first conscious impulse towards aggressive Nationalism’ to the brothers in the Mon, but the conventional assumption that the brothers were somehow responsible for ‘producing’ the revolutionary generation is now a matter of debate.It is more likely that those who went on to form the revolutionary elite in urban areas just happened to be those who were typical Christian Brothers pupils of this period – clever, ambitious boys from skilled working-class and lower-middle-class Catholic backgrounds whose parents regarded education as a route to upward social mobility. Whatever about the broader picture nationally, it seems clear that the Mon typified the faith-and-fatherland approach taken in at least some Christian Brothers schools in this period, whereby an emphasis on an Irish-nationalist interpretation of Irish history complemented Catholic indoctrination and Victorian classical education aimed primarily at preparing young men for the British civil service. A particularly formative influence on Barry was the Mon’s Brother Clifford, with whom he maintained a lifelong friendship. Originally from Castleisland, County Kerry, Clifford was an ardent advanced nationalist who ended his religious instruction classes with a call for ‘three Hail Marys for the welfare of Ireland, for the advancement of the Irish language, and that we may die for Ireland’. He also taught a number of selected students, many of whom ended up as Volunteers, how to use a gun, bringing them for shooting practice after school with his .22 rifle. In the early years of the new century, however, the brothers in general were seen by Irish-Irelanders as an ‘enemy of Gaelic culture’, primarily because of the playing in their schools of ‘foreign’ (that is, British) games, especially rugby. The Mon was among them and Barry was involved in the successful campaign to extend Gaelic games to schools and colleges, including his alma mater. This was regarded as essential to, in the words of Republican and Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA) official Thomas F. O’Sullivan, ‘saving thousands of young Irishmen from becoming mere West Britons’ and, in Barry’s own words, ensuring the GAA’s place in ‘the fight for national regeneration’.

Whether the brothers ‘produced’ a generation of re- volutionaries or not, they certainly cemented the Catholic- isation of Irish nationalism among many of this cohort. Religion was as central to Barry’s identity as was his Irish nationalism, local patriotism and his class; in his youth he served as an altar boy at the local St Vincent’s church, and later as a mass attendant, and was active in the Catholic charity work of the St Vincent de Paul Society. However, he consistently opposed religious sectarianism in politics, epitomised for him above all by the Ancient Order of Hibernians-Board of Erin (AOH-BOE), a component of the Home Rule movement that became an immensely powerful force in Irish politics and society from 1907 to 1918. His hatred for this political faction led him to politically identify for a period with its key opponent in the constitutional nationalist field, William O’Brien’s All-for-Ireland League.

Catholicism and Irish Republicanism coexisted com- fortably for most Irish rebels of this era, and for a fewer number, Barry among them, a socialistic outlook was added to the mix – essentially an advanced-nationalist syndicalism based on James Connolly’s late-career approach, wrapped in the Catholic social principles of the 1891 papal encyclical Rerum Novarum. While Barry’s labour Republicanism was centred on the trade-union movement (and, for a time, the labour-nationalist element in the All-for-Ireland League), it later entailed a rhetorical support for the Bol- sheviks when they seized power, and for the red flags and slogans of post-war international socialism, but not an ad- herence to the full spectrum of Marxist, and certainly not Marxist-Leninist, ideology. His devout Catholicism fused with a generalised left-wing analysis and labour activism to make Barry a Christian socialist, a worldview epitomised in these lines from his final published poem, ‘The Future War’: ‘And we’ll teach the boss that the Bible says/ Go share with the poor your all’. (See Chapter 4 for a discussion of Barry’s Christian socialism.)

We do not know the context for his initial interest in socialist idea...