- 336 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

As the story goes: Jeff Bezos left a lucrative job to start something new in Seattle only after a deeply affecting reading of Kazuo Ishiguro's Remains of the Day. But if a novel gave usAmazon.com, what has Amazon meant for the novel? In Everything and Less, acclaimed critic Mark McGurl discovers a dynamic scene of cultural experimentation in literature, with a confidence that rivals modernism. Its innovations have little to do with how the novel is written and more to do with how it's distributed online. On the internet, all fiction becomes genre fiction, which is simply another way to predict customer satisfaction.

With an eye on the longer history of the novel, this witty, acerbic book tells a story that connects Henry James to E.L. James, Faulkner and Hemingway to contemporary romance, science fiction and fantasy writers. Reclaiming several works of self-published fiction from the gutter of complete critical disregard, it stages a copernican revolution in how we understand the world of letters: it's the stuff of high literature - Colson Whitehead, Don DeLillo, and Amitav Ghosh - that revolve around the star of countless unknown writers trying to forge a career by untraditional means, Adult Baby Diaper Lover erotica being just one fortuitous route. In opening the floodgates of popular literary expression as never before, the Age of Amazon shows a democratic promise, as well as what it means when literary culture becomes corporate culture in the broadbest but also deepest and most troubling sense.

With an eye on the longer history of the novel, this witty, acerbic book tells a story that connects Henry James to E.L. James, Faulkner and Hemingway to contemporary romance, science fiction and fantasy writers. Reclaiming several works of self-published fiction from the gutter of complete critical disregard, it stages a copernican revolution in how we understand the world of letters: it's the stuff of high literature - Colson Whitehead, Don DeLillo, and Amitav Ghosh - that revolve around the star of countless unknown writers trying to forge a career by untraditional means, Adult Baby Diaper Lover erotica being just one fortuitous route. In opening the floodgates of popular literary expression as never before, the Age of Amazon shows a democratic promise, as well as what it means when literary culture becomes corporate culture in the broadbest but also deepest and most troubling sense.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Everything and Less by Mark McGurl in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literary Criticism for Comparative Literature. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Fiction as a Service

Amazon as Literary History

Should Amazon now be considered the driving force of American, perhaps even world, literary history? Is it occasioning a convergence of the state of the art of fiction writing with the state of the art of capitalism? If so, what does this say about the form and function of the novel—about its role in managing, resisting, or perhaps simply reflecting the dominant forces of our time? How has the novel’s long history as a purveyor of fictional worlds prepared it, or not, to speak to those forces in ways that readers still find compelling? These are the broad questions with which this study begins and by which it hopes to begin to draw critical attention to what is surely one of the most historically novel if as yet largely unexplored features of contemporary culture.

Amazon is at once exemplary and odd. It is a paragon of the contemporary corporation operating under the conditions of what was once enthusiastically called the New Economy, in which dramatic advances in information and communications technology would in theory change the game to the benefit of one and all. Like the magic systems portrayed in epic fantasy, the new corporate IT would surely if somewhat obscurely magnify the possibilities of human agency, making wizards of us all. In the event, it has made some men very rich while reinforcing the precarious dependency of most men and women on a system of economic arrangements not of their making. A system in which, under the watchful eye of the stock market, what is rewarded is ruthlessness in the management of employee armies and casting of spells. And Amazon is nothing if not ruthless, having become notorious for the aggression with which it pursues its own interests under the banner not of king or country but customer.1 With its brutally efficient management of the warehouses it calls fulfillment centers, with its predatory relation to the businesses with which it competes, Amazon exemplifies a corporate world that has returned in recent years to more savage conditions rather than advanced to a higher state.2

It is however strikingly distinct from its corporate brethren in several ways, not least in its uniquely intense and ongoing self-association with literature and the book. Not unrelatedly, and notwithstanding the controversy that so often follows in its wake, it has become a service so useful and convenient to readers as to thwart all but the most determined efforts to resist its charms.

Launched in 1995 as an online bookstore, Amazon’s receipts from books had by 2014 shrunken dramatically as a percentage of the company’s estimated $75 billion in yearly revenue, to something like 7 percent, as the company began to compete with Walmart for the prize of being the largest retailer in the world. That percentage is no doubt even smaller now, with 2020 revenue coming in at $386 billion, a nearly fivefold increase in only six years. And yet, if books are now only a fraction of the business of Amazon, that fraction is no small part of the book business, exceeding half of all US book purchases. The number is even higher for electronic books, a market Amazon did not invent but which it unquestionably made with the introduction of the Kindle e-reader in 2007.3 Greater still is Amazon’s dominance of the market in popular genre fiction. It has proved especially amenable to electronic consumption and is at the core of the $9.99 per month Amazon Unlimited e-book subscription service, now with several million subscribers. The latter points to an aspiration for serial plenitude over singular encounters in the reader’s relation to literature; to literature as a service somewhat like internet service or some other “always on” utility.

Intensely more observant of the realities of reading than publishing has ever been before, Amazon Unlimited pays royalties to writers based on the number of pages of their works the Kindle user actually reads rather than on their download alone. This distinction was part of the inspiration behind Amazon’s introduction in 2017 of Amazon Charts, an in-house weekly best-seller list divided into categories of “Most Sold” (familiar enough), but also “Most Read.” The latter integrates the wealth of data Amazon gleans from Kindle devices reporting back to the mother ship along with information on audiobook consumption, presenting a picture of what people are reading as opposed to simply buying. This is in addition to the myriad best-seller categories, numbering in the thousands, one encounters in any ordinary book search on the website, where, for instance, at one point in 2019, Delia Owens’s Where the Crawdads Sing (2018) held the No. 1 spot in Coming of Age Fiction, American Literature, and Women’s Literature and Fiction, while John Grisham’s The Guardian (2019) held the No. 2 spot in American Literature but was No. 1 in both Murder Thrillers and Small Town and Rural Fiction. Works like this claim the lion’s share of attention in the publishing industry as it is currently organized, yet with so many lists covering so many niches—Women’s Divorce Fiction, Australia and Oceania Literature, Teen and Young Adult Vampire eBooks, the list goes on—one feels there should be room near the top for almost everyone.

Book sales in the billions are no doubt motivation enough to keep the company focused on the readers who were its first customers, but in recent years Amazon has undertaken a series of initiatives that suggest a deeper existential commitment to the idea of literature, to getting inside literature, to being literary, than dollar figures can fully communicate.

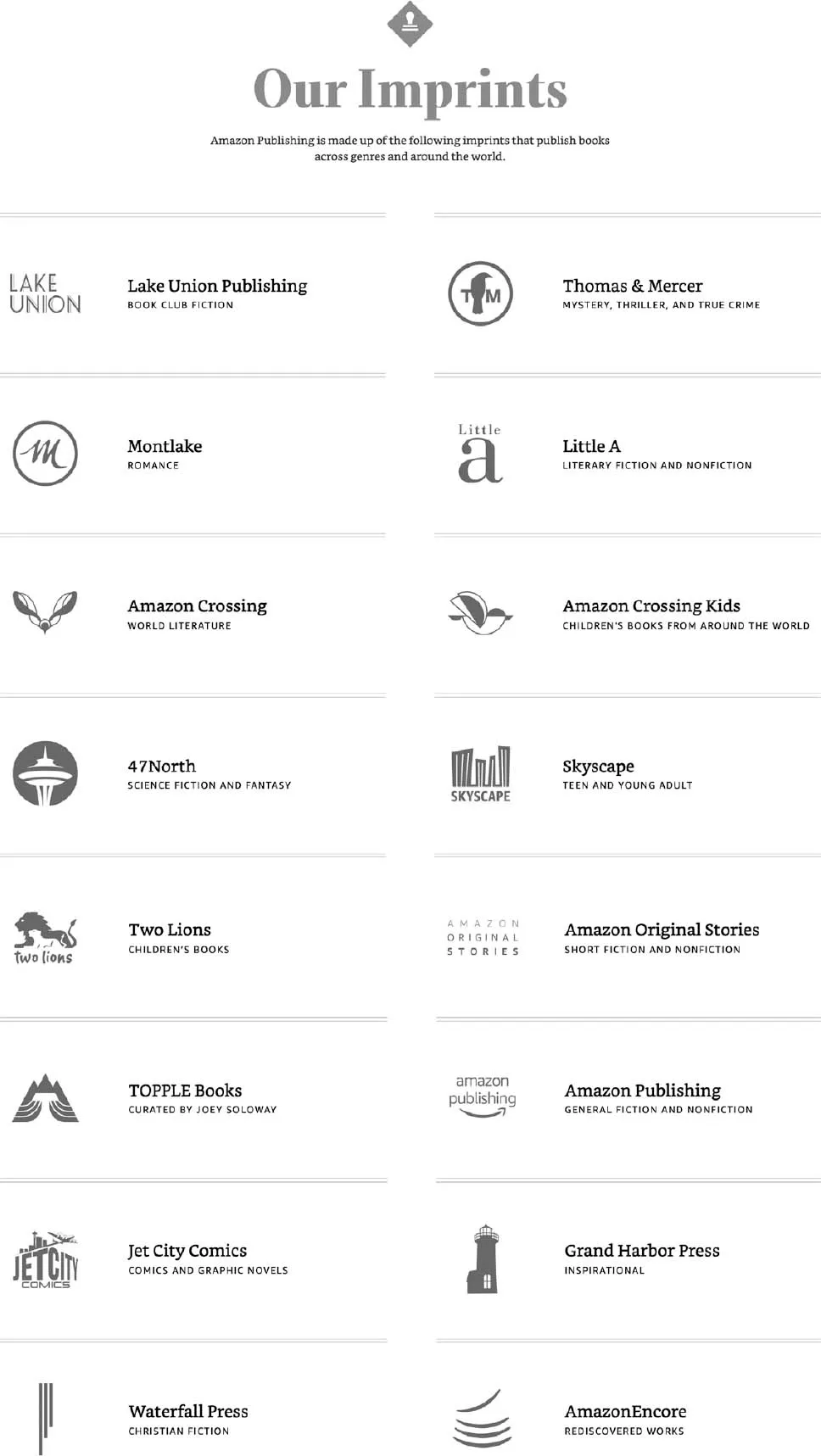

It has, first of all, become a traditional publisher with sixteen separate imprints, each tied to a separate genre, including one for literary fiction called Little A. The latter speaks to the persistence of the category of literary fiction as something unto itself, something putatively “un-generic,” but also to its demotion to the status of one genre among many, as we see in the figure on p.36.

Amazon Imprints A list of imprints that is also a snapshot, as from an overhead drone, of Amazon’s understanding of the contemporary genre system; that is, of the parceling out of the universal human desire to be told a story into separate modes of fulfillment keyed to different audiences and taste profiles.

Perhaps the most interesting and lively of these imprints is Amazon Crossing, which under the leadership of editorial director Gabriella Page-Fort has become the most prolific publisher of literary translations into English in the world. We will return to it in chapter 2, where the relation of Amazon’s corporate multinationality to world literature is brought to the fore. All told, the Amazon imprints have published thousands of books and are still growing despite the unwillingness of most bookstores to carry them, not wanting to help a company gunning for their business. Notably, whereas in the publishing industry at large, total sales of adult nonfiction generally outdo those of adult fiction, the vast majority of Amazon Publishing’s books are novels, suggesting an intriguingly excessive commitment on its part to fictionality.4

More innovative, and more consequential to this chapter and indeed this whole book, has been Kindle Direct Publishing (KDP), which, for 30 percent of the proceeds on any electronic text sold but at no further cost to the author, was designed to circumvent the traditional gatekeepers of American literary production, ushering in a new age of self-authorized popular creativity and low-cost literary entertainment.5 Although it is difficult to find exact data, it would appear that millions of texts have been self-published via KDP, and that hundreds of them have sold hundreds of thousands of copies—albeit, at cover prices sometimes as low as 99 cents. KDP works in tandem with the hard-copy print-on-demand platform CreateSpace, acquired in 2005 and folded into KDP in 2018, and with Brilliance Audio and Audible.com, acquired in 2007 and 2008, respectively, thereby covering all the sensory modalities of the contemporary book. Kindle Singles, whose motto is “Compelling Ideas Expressed at Their Natural Length,” is fascinating for how it leverages technology against the traditional constraints of the physical form of the book, which has to be of a certain size to be shipped and displayed through regular channels, allowing writers to sell a single short story, or a novella, etc., as an e-text. Amazon has also acquired the book-oriented social media site Goodreads, now with more than a hundred million eminently data-minable registered users. Through its Amazon Literary Partnership program, it has doled out millions of dollars in grants to various literary organizations since 2009.

Contexts Distance from the center of the diagram is a measure of explanatory generality, which is a source at once of comprehensive power and of potential banality. To say, for instance, that contemporary fiction is a product of nature, or modernity, would be as absolutely true as it would be absolutely uninteresting unless those claims could be specified. To notice, in turn, that poetry lies on the periphery of the diagram is to see at once how all literary activity can be described as “poetic” in the loosest sense, but also how weak the specific influence of contemporary poetry on contemporary fiction is beyond its association with the “lyric impulse,” that is, the human predisposition to artful self-expression in words. A more specific influence on fiction is exerted by the university, and in particular by the creative writing programs where so many professional poets now work alongside fiction writers. As discussed at length in my book The Program Era, creative writing programs didn’t exist in anything like the form we know them until the postwar period, but they now figure as perhaps the most crucial institutional infrastructure underlying the production of literary fiction and poetry in the US, the sine qua non of innumerable careers.

Cumulatively, these ventures represent a highly interested practical theorization of the literary field, one which we are by no means obliged to accept, but which anyone hoping for an adequate sense of the realities of that field will be increasingly obliged to observe.

So where exactly is Amazon in this field? What does the institutional ground of contemporary literary production actually look like? This is the signal question asked by a new institutionalism in scholarly approaches to contemporary literature in recent years as it has sought to move beyond the abstractions —pre-eminently “postmodernism”—that have guided its interpretation for so long. Perhaps its looks something like the diagram in the “Contexts” figure on p.38, which, taking the relative coherence and reality of something called “contemporary fiction” as a given, represents a highly schematic plotting of the various institutions that can be said to influence its form.

At the top of the diagram one sees the university, whose importance to contemporary literature of a certain kind would be hard to overstate, especially to the lives of the great many authors who make a better living there as writing teachers than they could through book sales alone. Given that they stand alike as such striking literary-historical novelties, it seems fair to begin by asking: What is the relation between the “Age of Amazon” to the creative writing program? Observing the situation in 2021, one would have to say that they are merely adjacent literary-historical phenomena, although there is nothing standing in the way of their partial convergence in, say, the publication as KDP e-books of otherwise dead MFA theses. Juxtaposing these two entities, we immediately notice something interesting and possibly surprising, which is the relative lack of any real pedagogical dimension in and of the KDP literary ecology, which acts more or less as though the writing of good books will take care of itself. Confirming this lack, what the company calls KDP University is mostly a series of chats with self-published authors reflecting on how they achieved their success. In the same vein are the raft of how-to books sprung up to help writers navigate KDP, which could be thought of in a pedagogical light (see figure on p. 39). Certainly, Amazon is already hard at work conquering the campus bookstore and textbook (and other sundry) markets, as Barnes & Noble and Borders once did.

How-To The writing pedagogy facilitated by Amazon focuses more on marketing strategies than on the form and content of stories.

What the worlds of KDP and MFA already share is a professed allegiance to the artistic will of the people, and creativity in general, although Amazon represents a significant intensification of this populism, relatively unburdened as it is by that other half of the writing program’s mission: the conservation of more or less high modernist literary values and pursuit of traditionally exclusive literary prestige. One way of thinking about the Age of Amazon, then, is as a possible successor formation to the creative writing program, thereby foretelling the end of the Program Era. To the extent that the motive for getting an MFA is to become a “published novelist,” KDP offers considerably more efficient means to that exalted end. But, of course, there are many reasons to pursue an MFA degree other than that, so a literary historian must entertain the thought of pure supersession with skeptical caution. Indeed if, as seems to be the case, the rise of Amazon has been associated with an overall lowering of the incomes of full-time writers, the impetus for supporting themselves by teaching writing has become all the stronger, assuming enough students can be found to shore up the enterprise with their tuition money.

Here, however, I want to concentrate on the sector on the left side of the diagram, where one finds various ways of characterizing the properly economic environment of contemporary fiction. Amazon has a different sort of relation to so-called neoliberalism —that is, to the ideology of de-unionization, deregulation, privatization, financialization, and the dismantling of the welfare state that has dominated policy debates since the 1970s—than it does to the university writing program. While its relation to the latter is one of as yet uncoupled adjacency, its relation to neoliberalism is one of specification and thus, inevitably, idiosyncrasy. In the back-and-forth between empirical analysis and concept generation in materialist literary historiography, this specificity can be a real advantage, pointing, for instance, to the sheer oddness of the novel as a “neoliberal” commodity—not least, as we’ll see, in the way it structures time.

The same is true of Amazon’s relation to the internet, or more broadly to digital technology, including the personal computer, word processer, data server, and now social media. On the one hand, in a way that is not quite true for its competitors in the publishing business, the multinational conglomerates— HarperCollins, Hachette, Macmillan, Penguin Random House, and Simon & Schuster (at this writing, the latter two have planned to merge, pending approval by regulators)—who between them produce the lion’s share of books published in the United States, the advent of advanced digital technology and internet communication is the sine qua non of Amazon. Although it moves a great many physical objects through space, it is one of the original “dot-com” companies, as they were once called, a congeries of digitizations on the front and back end of its business.

To say that Amazon has arisen as a new and highly consequential agent in the unfolding of literary history is necessarily to say that the internet has, too. It was, after all, the latter that made Amazon possible, directly inspiring the company’s founding as an answer to the question, much on the minds of would-be entrepreneurs of the late twentieth century l...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Halftitle Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Preface: Bezos as Novelist

- Introduction: Retail Therapy

- 1. Fiction as a Service

- 2. What Is Multinational Literature? Amazon All Over the World

- 3. Generic Love, or, The Realism of Romance

- 4. Unspeakable Conventionality: The Perversity of the Kindle

- 5. World-Scaling: Literary Fiction in the Genre System

- 6. Surplus Fiction: The Undeath of the Novel

- Afterword: Boxed In

- Notes

- Index